MusicWeb International

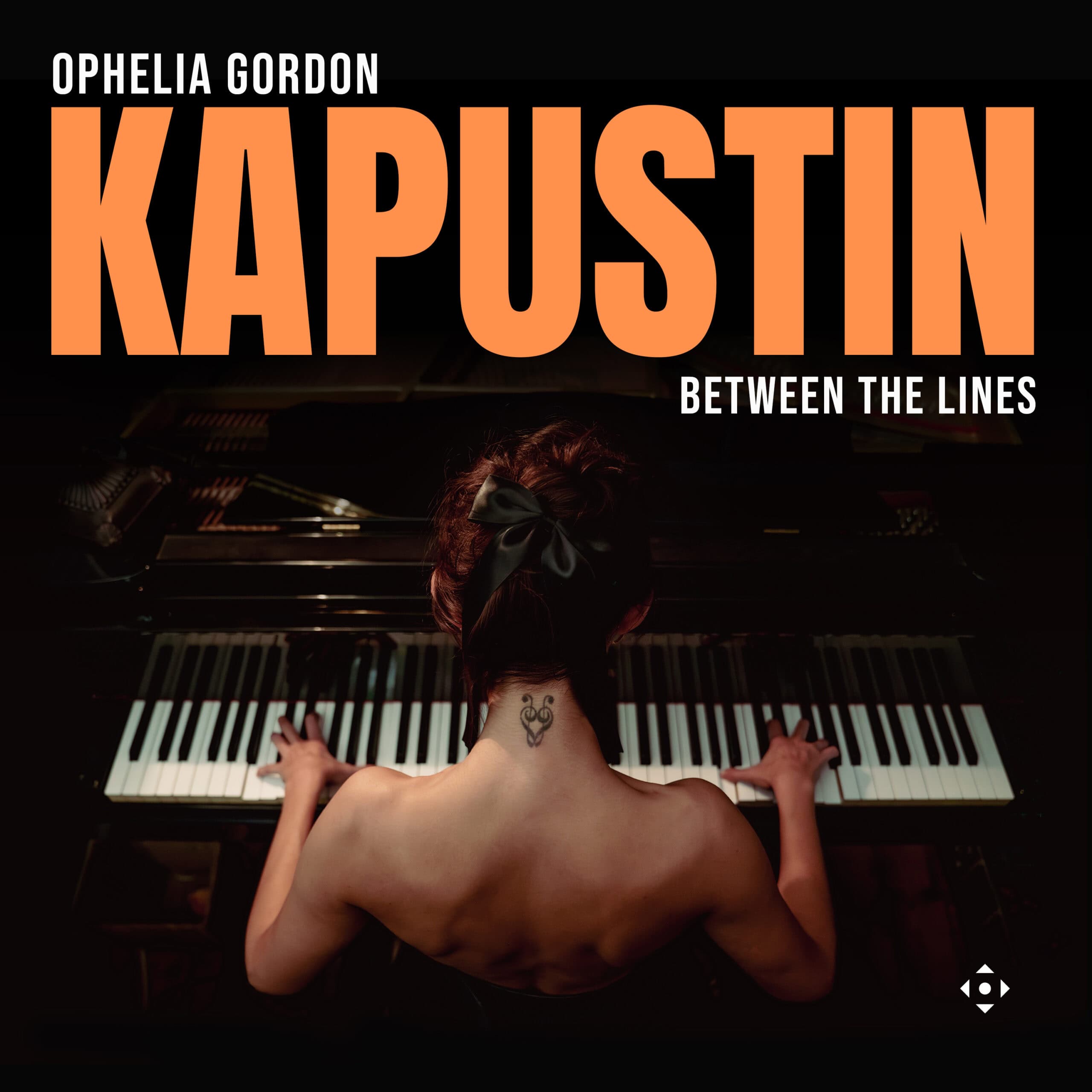

Nikolai Kapustin never saw himself as a jazz musician. He wrote: ‘I’m not interested in improvisation…All my improvisations are written, of course, and they became much better; it improved them.’ Whilst for some the idea of an album of wholly notated jazz pieces might be anathema as a point of principle, most people listening to Ophelia Gordon’s well-chosen recital might be inclined to agree with the composer. In his act of fusing jazz idioms with broadly classical structures there’s an obvious degree of creative calculation, but that never seems to inhibit the air of spontaneity which pervades.

There’s also lots of variety. The opening piece, Big Band Sounds, with its swing rhythm and brassy textures is instantly evocative of the form in Gordon’s characterful solo rendition. And there is a homage to individuals as well as genre in the Jazz Preludes that follow, with tributes to Bill Evans and Oscar Peterson amongst others mixed in with an attractive array of forms in the eight selections. Gordon captures the mood of introspection perfectly in Contemplation, which comes next, and it was an inspired decision to follow that with the Paraphrase on Aquarela do Brasil. As Gordon says in her booklet notes, Kapustin doesn’t just cover Ary Barroso’s famous standard in this piece, he ‘rewires’ it. The samba is never far away but the elements of the fantastic and virtuosic which one might expect in a concert paraphrase are very much present too in this sparkling account.

The Eight Concert Études which come next are probably Kapustin’s best known and most frequently recorded pieces, often played as encores, but it’s a highly enjoyable experience to hear them together here, as if one’s experiencing a whistle-stop tour of the history of jazz piano. With real flair and verve Gordon takes us from Art Tatum to Chick Corea with some interesting stops en route. There are some interesting Russian influences too: harmonies and chords which wouldn’t be out of place in Rachmaninov and at times a scabrousness that feels almost Shostakovian.

The final work is an ambitious realisation of another paraphrase, this time on Dizzy Gillespie’s Manteca. Kapustin wrote it for two pianos. Gordon writes that after unsuccessful attempts to find another pianist, she recorded the ‘rhythm’ part and then played the ‘melody’ part alongside it. This sounds in some ways like an obvious and straightforward solution but in practice needs a high degree of musical sensibility as well as technical skill. It succeeds triumphantly here. Gordon gives us the in the moment intensity and excitement of a live performance, revelling in another ingenious Kapustin reinvention, and showing us again that she is the ideal advocate for the composer’s music, All in all, great fun.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=iGIrDXgtiUoQ7kNvwHhEUx1&_nc_oc=AdkONWhsPmRakyxT3pKuXrRZDhBNbcKR6ELGzsLdaEBiMM3vTsUEpDS1iY1cZ4wOR_E&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=E2I3zDUGqThw1iLfr6FRPQ&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQFc9Af1HSBvMg_9r6gvHrHKBH1fojSQd00XqSKrgMrbT7H_OP8L3_JZX6eyYRkM2I-LB__6HAL57g&oh=00_AfyHCTaPe0YJ9BAnZaJJ6RtDNvJ-8380rDLC8Pl3oquskQ&oe=69B17781)