Fanfare

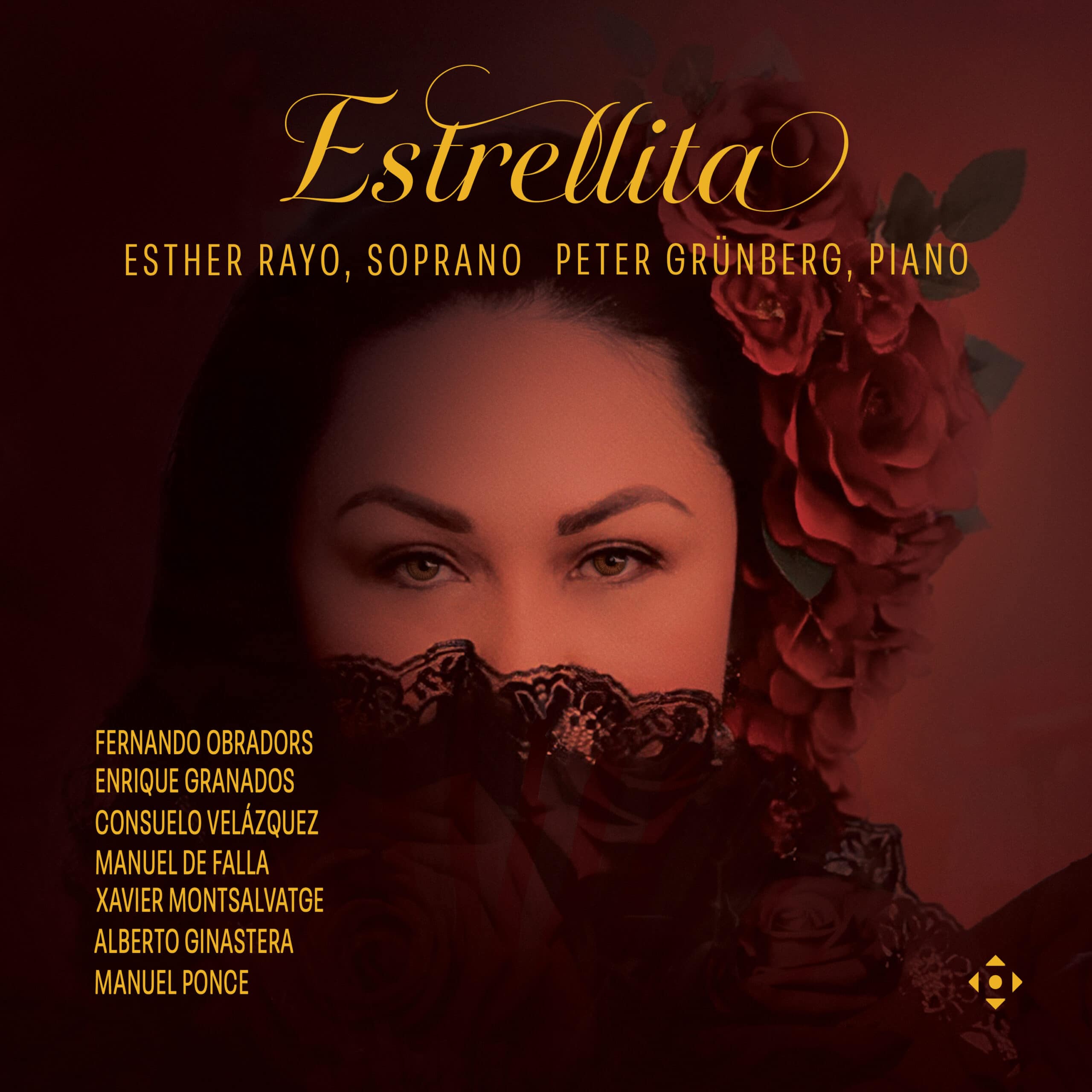

Esther Rayo’s new album Estrellita (Little Star) is a collection of Spanish-language songs from the first half of the 20th century, a time when the distinction between “classical” and “popular” music was considerably blurrier than it is today. As the anonymous liner-note writer for this release explains, “In contrast to the distinction implied in current English usage between the phrases ‘classical music’ and ‘popular music,’ the words ‘classical’ and ‘popular’ when applied to music in the decades before the second world war were words with similar meanings.”

I would date the division between “classical” and “popular” music considerably earlier than that. It really began with the advent of ragtime in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As ragtime was succeeded by jazz, swing, rhythm-and-blues, and rock ‘n’ roll the wedge between classical and popular music was driven deeper and deeper, until the connection was severed altogether. And they remained apart despite various attempts to bring them back together—the “symphonic jazz” of Paul Whiteman in the 1920s, the “progressive jazz” of Stan Kenton in the 1940s, the “Third Stream” music of the 1950s, the “progressive rock” of the 1970s.

Esther Rayo was born in California but was surrounded by Spanish and Latin American music from her earliest days. For Estrellita she picked a fascinating selection of songs, all written in Spanish but not all by Spanish composers. Alberto Ginastera was Argentinian and the two pieces here closest to what’s commonly thought of as “popular music,” Consuelo Velásquez’s “Bésame Mucho” and Manuel Ponce’s “Estrellita,” are from Mexico.

The pieces are mostly in chronological order, and one can hear a slight but unmistakable evolution in the sophistication of the musical language from the relative primitivism of Fernando Obradors to the more sophisticated Enrique Granados and Manuel de Falla and the outright, albeit conservative, modernism of Xavier Montsalvatge and Alberto Ginastera. Montsalvatge also incorporates a few jazz licks into his selections. The texts likewise show a similar advance, from the 16th century poems Obradors set to the contemporary literary pieces the other composers used. Velásquez and Ponce wrote their own texts.

Esther Rayo sings the songs on this album with a remarkably clear, pure tone. Falla’s Siete Canciones Populares Españolas were premiered in 1915 with zarzuela (Spanish operetta) singer Luisa Vela and Falla as pianist. Falla made the first recording in 1930 with coloratura soprano Maria Barrientos, though it was eclipsed by another 1930 recording with mezzo-soprano Conchita Supervía and Frank Marshall on piano. Ironically, despite their reputations as opera singers, both Supervía and Victoria de los Ángeles, on her 1955 disc with Gerald Moore, sang them in a much more “folky” style than Rayo, adding growls and smears and rolling their “r”‘s. Rayo sings Falla’s songs with opera-style tone.

When I first got Rayo’s Estrellita for this assignment, I chuckled at the irony that I was being asked to review for Fanfarea program that included a song, “Bésame Mucho,” that The Beatles had covered. (They didn’t put it out commercially during their years as a working band, but they played it at their auditions for Decca and EMI in 1962, and the EMI version was finally released on the first volume of The Beatles’ Anthology in 1995.) The anonymous annotator was actually ahead of me, referring to versions not only by the Beatles but Andrea Bocelli, a singer on the cusp between classical and popular music.

My one aggravation with this album is that two of the song cycles—the Falla and Montsalvatge’s Cinco Canciones Negras—are given incomplete. The Falla is missing the next-to-last song, “Canción,” while the Montsalvatge leaves out the middle, “Punto de Habañera.” While luckily there are complete recordings of these cycles readily available (de los Ángeles did Cinco Canciones Negras on Cantos de España in 1962, albeit in an orchestrated version), including the missing songs would have added just four minutes to the total running time and made this release more valuable.

At least the first book of Obradors’s songs and Ginastera’s cycle are both given complete, and while we get just three of Granados’s 12-song Tonadillas en Estilo Antigo, the ones we do hear form a continuous whole. They are subtitled La Maja Dolorosa (The Sorrowful Woman), and they tell the story of a young woman whose lover has just died. Together they make a remarkable musical portrait of the heroine going through the stages of grief as she reconciles herself to his death and, in the last song, chooses to focus her thoughts and memories of him on the happiness they shared.

All in all, Estrellita is an excellent release. The songs themselves are almost all about love—mostly obsessive love—and Rayo and her accompanist, Australian-born Peter Grünberg, are very much on the same wavelength. The album successfully creates a romantic, elegiac mood. Grünberg also gets one piano solo on the disc, “Quejas, o la maja en el ruiseñor” from Granados’s cycle Goyescas, though since Granados later set this to words and inserted it into an opera of the same title, it would have been nice to hear Rayo sing it. Estrellita is a lovely look at a musical world that is largely unknown to all too many people outside Spain or Latin America.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

We noticed you're visiting from United States (US). We've updated our prices to United States (US) dollar for your shopping convenience. Use Pound sterling instead. Dismiss