MusicWeb International

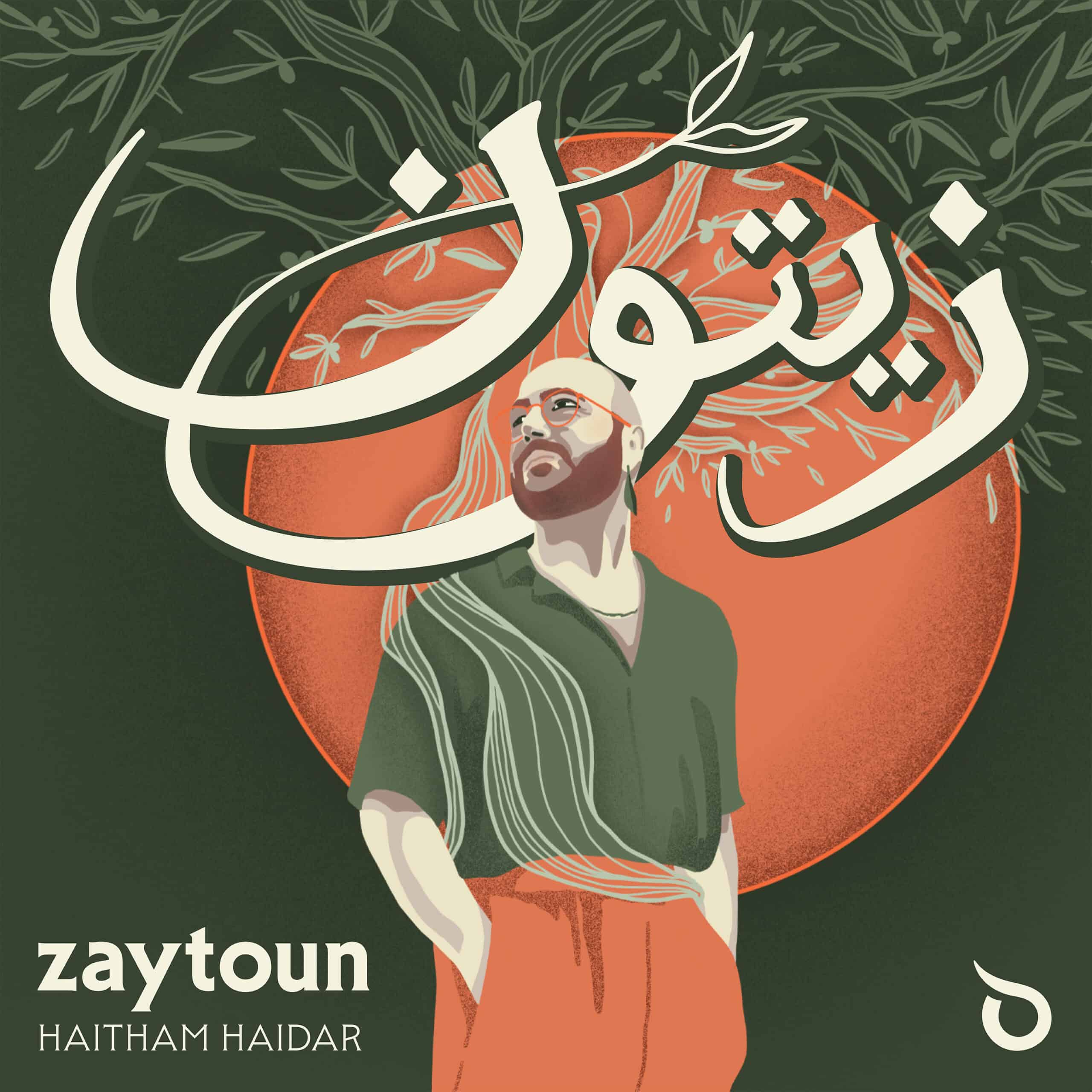

Haitham Haidar’s Zaytoun is one of the most striking solo debuts I’ve experienced for some time. Haidar is a young Lebanese-Palestinian-Canadian tenor who has already distinguished himself in the world of baroque music. But as he writes in a direct and affecting booklet note Zaytoun was conceived at a time of ‘heavy strife and internal conflict…Suddenly in in my journey, I felt lost. My voice felt lost. It didn’t know where it belonged. Though I may have trained my voice in one genre, my heart felt like it belonged to another.’ His way forward was to record an album which joined his Arabic roots with his love of the baroque, with the hope that by doing so he would bring the two worlds closer together. Now, I defy anyone to read Haidar’s introduction and not will him to succeed in his ambition. That’s where I was as I put on the CD for the first time. But recitals which seek to juxtapose such cultural diversity are sometimes difficult to bring off. As the disc started playing, I was asking myself whether allowances would need to be made to talk in order to talk about the performance constructively. It was quickly obvious, however, that this was something special.

In the first place it’s rapidly apparent that an inordinate amount of care has gone into planning the recital, for which Haidar was also the producer. There is the primary consideration of which pieces to choose and how to order them. This is superbly effected and there’s a wonderful arc to the programme which I’ll return to. Then instrumentation had to be considered. Haidar elected to go with a small group of four baroque players utilising plucked and bowed strings and harpsichord, plus an oud. Crucially though, those instruments aren’t restricted to the pieces one might expect, with magical results. Finally, Haidar decided to frame the recital with extracts from Gibran Khalil Gibran’s poem The Prophet. This was risky, because not done well it could have been distracting and sententious. But Haidar makes it work. He reads the passages with poise and feeling, to the gentle accompaniment of Abdul-Wahab Kayyali’s improvisations on the oud. So performed, Gibran’s words acquire an additional luminescence and add an important component to the musical items and the structure of the programme.

Haidar’s singing throughout has an arresting warmth and lyricism, immediately apparent as he launches into the first sequence consisting of two songs by Sayed Darwish, described as the ‘father of Egyptian popular music’, surrounded by two Monteverdi extracts. Nigra sum from the Vespers is laid out with a lovely simplicity with Haidar showing true depth to his range with Monteverdi’s lower notes sonorously sung, and Sylvain Bergeron’s archlute providing colour and dignity. Darwish’s El Helwa Di is an exuberant morning hymn featuring Amanda Keesmaat’s cello and Abraham Ross’s harpsichord as well as Kayyali’s oud. The second Darwish number, Zourouni, is a folk infused melody, and it’s an inspired contrast with Monteverdi’s Lamento della Ninfa which follows. Suddenly, from the simple oud accompaniment to Zourouni, the texture lights up for the Monteverdi with Haidar providing multitrack harmonies for his solo line. It’s a delightful transition, one of many on the album.

The contrasts and confluences continue with Purcell’s Music for a While, where the inclusion of the oud in the arrangement feels natural and appropriate and then Wa Habibi, a traditional hymn used in Arab churches on Good Friday, possessing a very familiar melody, taken from the French folk tune Au Sang Qu’un Dieu, also used as the basis for the Catholic hymn God of Mercy and Compassion. Haidar sings it with a hushed lyric reverence.

I talked about the arc of the programme earlier, and to me it felt as if it reached its zenith with the next music, which is an extraordinary arrangement of Erbarme dich, mein Gott from the St Matthew Passion. It’s scored for all the instruments we’ve encountered so far, i.e. oud, cello, archlute and harpsichord plus the beautifully played baroque violin of Tanya LaPerrière. The texture feels perfectly judged with the oud adding a slightly unsettling touch so that we really feel we are hearing something deeply familiar with a new ear. That feeling is only reinforced when we realise Haidar is singing Picander’s verse in Arabic in his own translation. It’s a remarkable experience. As Haidar says, the Arabic seems to fit the music naturally, somehow deepening the air of melancholy that is already present. His singing is graceful and heartfelt, as one with the exquisite instrumental accompaniment. I was reminded, appropriately, that Edward Said once wrote about the necessity of ‘understanding Bach from within’. It seems to me that Haidar here has achieved that, but not just for himself. He has generously given us the chance to share his perspective too.

The final segment of the recital has much to commend it: a performance of Danyel’s Grief Keep Within, where Haidar explores the boundaries of sorrow with a rawness that provides an interesting contrast to the text’s exhortation to ‘scorn to show but tears’; Rodrigo’s desperately poignant Li Beirut, setting Joseph Harb’s lament for the city laid low by the Lebanese civil war; Honoré d’Ambruis’s Le doux silence de nos bois rendered with charming simplicity by Haidar and Bergeron; and the traditional Palestinian song Ya Taleen in a mesmerising setting for 5 multitracked voices and cello.

‘Zaytoun’ means ‘olive’ in Arabic. It’s a fruit that features in dishes in the East and West and it feels appropriate that it should give its name to this exploration of two interlinked cultures. I think Haidar’s stated aim, that his music should show us that the distance between the two is not as great as we think, is wonderfully realised.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978