Fanfare

This is a disc to cherish, a mix of the well-known and the “why haven’t I heard his before?”. Rayo and Grünberg have chosen their repertoire carefully, and lavish love, experience and wisdom upon it.

Only a couple of the texts to songs of the Obadors selection here are not by that well-known composer Anonymous. The text of the first on show here, “El paño mouno” is by Juan Ponce. Its placement is perfecly judged; it feaures solo voice, sans piano, after an initial flourish (which itself shows how well recorded the Steinway piano is). “La mi sola” is the text, appositely. Esther Rayo’s voice is ravishing, but not overbearing in its timbre; Grünberg’s incisive playing fits the cut of the music perfectly. Cristóbal de Castillo furninshes the wods of “Àl amor”. A witty song of excess in love, Rayo is as playful as you like; careful listening reveals how accurate the melodic lines are, even at speed. Anonymous asks why his heart stays awake when is master wants to rest. The piano part is markedly difficult in its disjunction, and Grünberg is superb, specifically how in the transitions from staccato to legato; Rayo’s handling of the text is as careful as if this were a Schubert song; we intrinsically believe the questionings. There is no missing the Spanish rhythms of “El Majo celoso” (The Jealous Majo). The tale is charming, of a lady concerned with the jealous motions of her present lover. To a text by Juan Ancheta, “Con amores, la mia madre” is a song about a mother putting her child to sleep, a lullaby shot though with nostalgia. Here, pulse and rhythm dance to create a song culminating, here, with the most exquisite floating high note from Rayo. Finally for the Obradors set, the anonymously penned “Del cabello más sutil” (Of the softest hair). Washes of sound from the piano remain firmly non-French Impressionist, but very much of the composer’s place and time. A song of longing, the text is infinitely touching; so is this performance.

Some might be familiar with Lucrezia Bori’s 1937 performance of another Obradors song, ”Sonsejo” (with an unnamed pianist), a master performance in this repertoire. José Carreras is rather less persuasive with Martin Katz in “Corazón, porque pasais?” (the third song heard here). Three of the six pieces selected by Rayo and Grúnberg un up on an album by Kathleen Kim on Decca, but they are accompanied by guitar (Jong Ho Park), well performed by both, so a useful alternative take. It is the final song that has the most competition though, from the likes of Carreras, Kathleen Battle, Elly Ameling and Shiley Verrett. Big guns (I’d be hard pushed to pick between Verrtt and Ameling; this last surprised me somewhat).

Granados is more familia ground. Rayo stands her own against the hallowed Victoria de los Angeles in the three “sorrowful women”. The songs are actually three different reactions to bereavement. We certainly feel the protagonist’s pain in the first, with the piano notably heavy with grief. And while Victoria de los Angeles is indeed impressive, Rayo also goes up against Pilar Lorengar, with Alicia de Laroccha on the piano, an unforgettable account that leaves one chllled and numb. Rayo and Grünbeg are almost there, and certainly hold their heads high. The second of the three songs deals with denial as part of the grief process; it is multivalent, as realizations of mortality jostle with denials. Here, I find Rayo more convincing than Lorengar; it is Lorengar’s slightly quick vibrato hat gets in the way. The combination of Rayo’s smooth line and Gürnberg’s guitar-like staccato in the third is a winning one. Rayo’s lower extension is superb, too; I find her just as convincing as my preferred version of this song, Teresa Berganza and Félix Lavila on Decca,

Good to have a piano “interlude” to break it up, especially since Grünberg has shone so far. It is from the third book of Goyescas, “Quejas, o la maja y el ruiseñor”. Grünberg is close in his response to de Larrocha in the later recording; a tad over-langorous. The extremely talented pianist Javier Perianes in his recent (2023) recording offers a fresher take (I like him here more than my esteemed colleague Huntley Dent: Fanfare 47:5).

The 1941 song Bésame mucho by Consuelo Velázquez is ostensibly phenomenally crafted easy listening music. Small wonder Joseph Calleja recorded it with the BBC Concert Orchestra (resident more at BBC Radio Two than the more Classically oriented Radio Three; although the lines are getting blurred these days). From Domingo to Alagna, they opt for orchestra; here, we have a mysterious, brilliantly non-easy listening intro; the entire song’s foundations are reframed to a more sophisticated space. Still a. slinkily sexy one, but we seem to enter the dark side of sensuality. There’s more to the text’s request for kisses than one might think, Rayo and Grünberg seem to be saying. This is a whole other proposition (if you’ll pardon the pun), and.a far better one. Forget Calleja and friends; this is where it’s at.

Another selection from a set of Canciones populares españolas: this time, six out of the seven (just omitting the sixth, “Canción”) by de Falla. Love with a capital “l” is how the present booklet notes describe these songs, and how right they are. Grünberg’s crisp playing in “El paño mouno” underpins Rayo’s beautifully smooth lines. Few singers get “Seguidilla murciana” so right as here, Grünbeg’s playing is so preternaturally even and nuanced; Rayo tells the story of infidelity compellingly. Together, Rayo and Grünberg convey the intense sadness of “Asturiana” spellbindingly, while Grünberg triumphs over the difficulties of the opening of “Jota” with seeming ease. Duets between Rayo and piano lines wok superbly, but most of all it is the color both musicians glean from their respective instruments (with the voice as instrument) that impresses here. It is fascinating, too, how they create a haze in “Nana,” but again it is nothing like a French Impressionist haze; this is far more region-specific and carries its own mystery in this lullaby. Finally, the lament of being cursed in love (Love!) that is “Polo”, the piano guitar-like in one sense gesturally but here a powerhouse of energy of its own. Falla’s snake-charmer’s melodic shapes are beautifully, smoothy done by Rayo.

The list of contenders here is cast, including all the usual suspects in this repertoire (de los Angeles, Carreras, Berganza et al). But I enjoyed Rayo/Grünberg as much as any of them. They also boast compellingly present sound that underlines the involving aspect of their riveting performances.

It is really good to see music here by Xavier Montsalvatge, albeit a selection from his most famous piece, the Cinco Canciones negras. I have long been fascinated by this composer: Naxos has done sterling work, and it was a pleasure to be at the UK premiere in October 2013 of his opera El gato con botas (Puss in Boots: in a 1996 chamber version by Albert Guinovart). That piece was written in 1948, so while the there is good work being done, there is clearly yet more to achieve. The principal competition for the songs here is surely Montserat Caballé and Alexis Weissenberg (the LP was reviewed in Fanfare 03:6). Rayo has Caballé’s clarity of diction, and almost matches her story-telling qualities, while Grünberg almost takes us into the realms of a smoky late-night jazz club at one point. Fascinating. It is the second we hear (No. 3 in the set) that is truly heart-rending, though, “Chévere” (The Dandy), a curious mix of violence and regret. The lullaby is the most famous of the set, for sure, and is heard in a lilting performace where dissonances cut like the Dandy’s knife. The “Canto negro” is one of those songs with a chattering piano part that requires complete evenness, which is certainly the case here. Dialogue between vocal line and biting piano accents is perfect, and Rayo despatches the line with huge character.

Alberto Ginastera certainly is better known than Montsalvatge, but there are still pieces that need a helping hand: it is wonderful that the Miró Quartet has released a vibrant recording of the string quartets recently on Pentatone, for example. The 1943 Canciones Populares Argentinas perhaps do not need quite a leg up, and benefit from a fine recording by Lawrence Brownlee and Iain Burnside on Opus Arte (see Lynn René Bayley’s review in Fanfare 37:2). I have not always been a fan of Brownle, but a recent Opera Rara disc of Donizetti songs convinced me beyond doubt of his merit. The first song begins here with a nervous repeated note from Grünberg; Rayo adds to the nervous tension. This is almost like a live performance, but with all the right notes. The move to “Triste” (Sad) is stark indeed, and Rayo and Grünberg’s holding of the inter-phrase silences is superb; as is Rayo’s upper register, with no sense of strain whatsoever. “Zamba” is a sad example of that dance, of twisted love logic that seems to the protagonist , at least at the moment of creation, to make sense. I love the dissonances Ginastera brings to a lullaby (“Arroró”), subtly nudged by Grünberg; Rayo’s half-voice, almost offering a vocalise but then morphing into words, is beautiful. And so to a cat. Not one in boots this time, but one that is most boisterous. The piano par is fiendish, and Grünberg gives his all; it is up to the singer to match him, and how Rayo throws herself into the text. This is a superb close to the set (and would make a perfect encore to a recital, too).

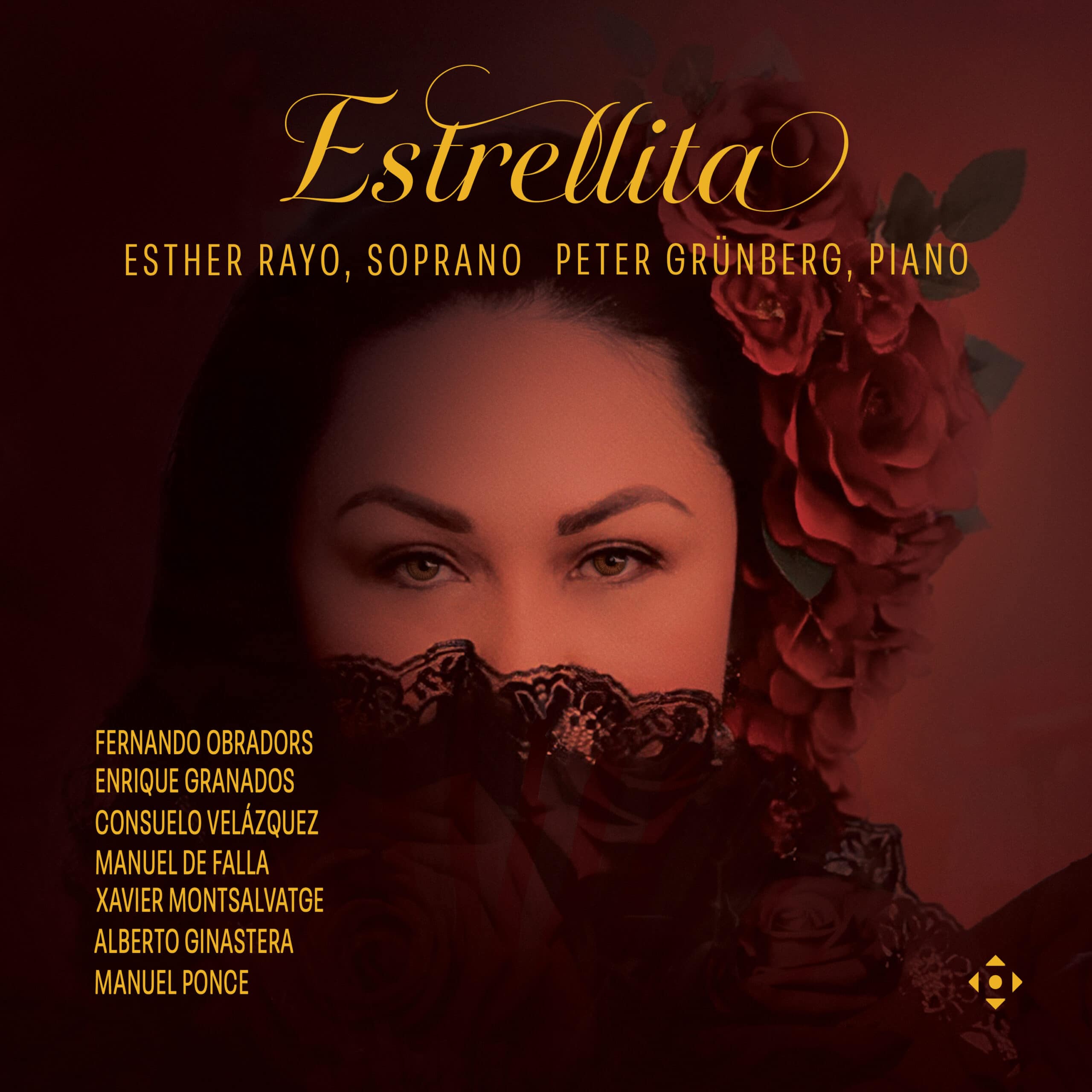

It would make a terrific close to the recital here, too, but it is not what actually ends the disc. This is the titular track, Estrellita (Little Star), by Manuel Ponce. The booklet noes suggest the star’s brilliance and clartiy are at the heart of this recital, and I would agree. The song is a lovely little morsel, and the link is clever. It works as an outro; I just do not find it their best performance though, despite a nicely soaring soprano line at the end.

That is, though, a tiny caveat: this is a major release. Rayo is a star, and not a little one; Grünberg is the perfect collaborative pianist. For someone looking for a first disc of songs of this ilk, this would be perfect; Rayo and Grünberg have completely internalized this repertoire. But it will also bring enrichment to jaded old listeners and critics (such as myself). Superb.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978