Fanfare

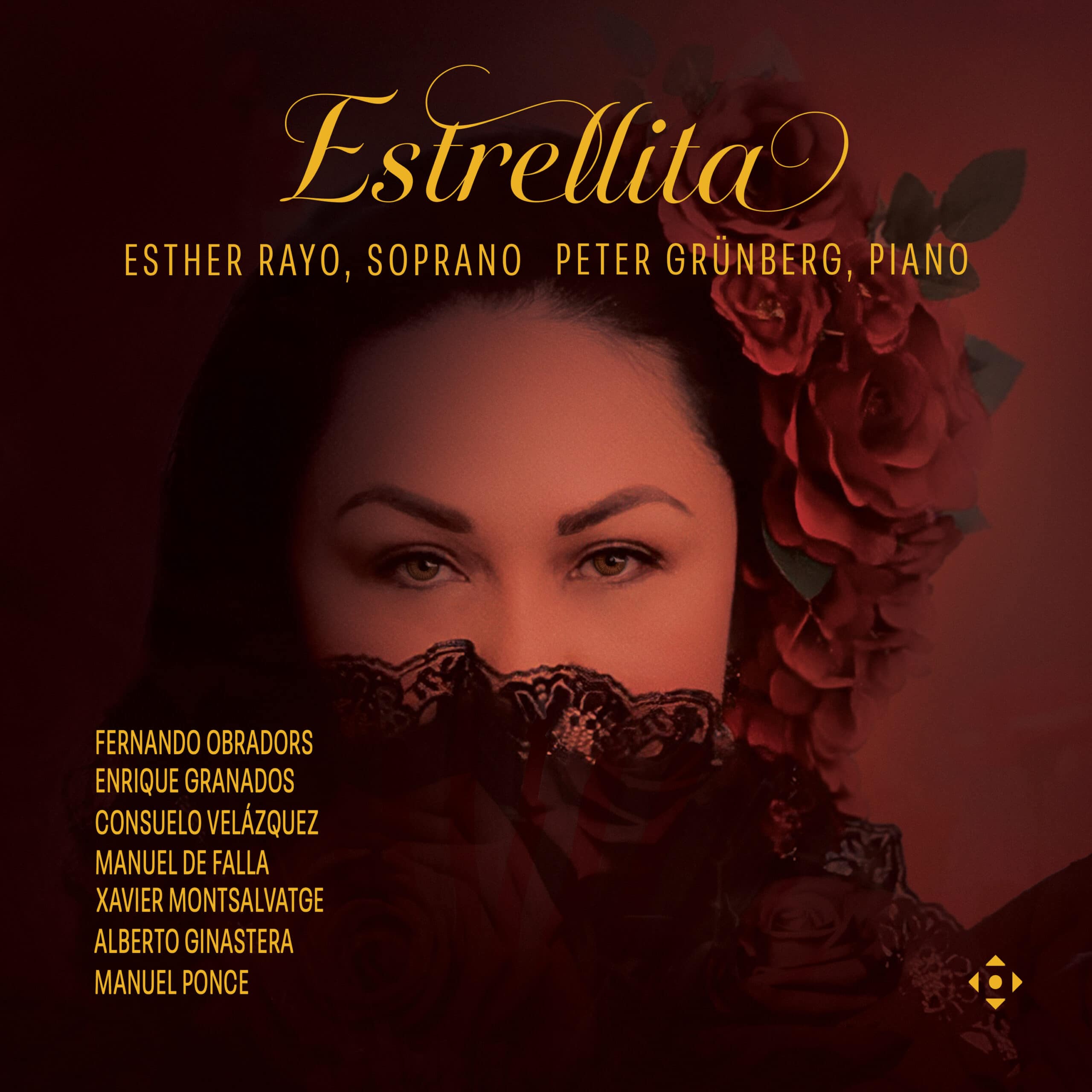

Spanish songs are peripheral for general listeners despite the wealth of melody, color, and vibrancy that they represent. It takes an international opera star like Victoria de los Angeles to bring even the most popular songs by Falla into the limelight, and she did her best to record many more Iberian composers. Decades can pass with few first-rate singers taking up the torch, which makes it particularly delightful that American soprano Esther Rayo presents this broad selection from seven composers in songs composed during he first half of the 20th century. Without being an international Spanish opera star, Rayo is a first-rate exponent of this material—to my knowledge, there hasn’t been a Spanish song recital of this caliber in a long time.

The program includes six selections from one of de los Angeles’s specialties, Falla’s irresistible Siete canciones populares españolas, which Rayo sings with more than a touch of the great singer’s piquancy. But Rayo’s warmly feminine timbre reminds me more of Teresa Berganz. She uses her voice very musically, reflecting a deep familiarity with Lieder, which Rayo has performed notably, particularly from her base in the Bay Area. The ornamentation and melisma so typical of Spanish vocal style comes easily and naturally to her; she phrases sensitively with attention to the text. Her comfort zone is wide enough to encompass idioms that range from folksong to art song. Rayo also has the gift of communicating immediately with the listener, in no small part thanks to her voice’s tonal beauty.

Except to specialty collectors, these 27 songs are likely to be either unknown or only sporadically familiar, with the exception of the popular hit, Bésame mucho, by Consuelo Velásquez. This brings up a salient point from the very readable program notes by pianist Peter Grünberg. Spanish composers of the era of Falla, Granados, Albéniz, et al. drew upon native musical roots that cannot be distinguished as popular instead of classical, or vice versa. The first group of songs on the program are selected from the seven books of Clássicas canciones españolas by the Catalan composer Manuel Obradors, where the word “clássicas,” Grünberg informs us, is being applied to both the well-known poems Obradors set and the melodies that endured and attained classic status over the centuries.

The same deep-dyed cultural heritage enters the entire program while taking on individual mood, color, and rhythm from each composer, all the way to Alberto Ginastera’s thorough knowledge of Argentinian folk traditions in his Cinco canciones populares argentinas of 1943. But as Spanish composers confronted the flowering of modernism in the decades after 1900, they became aware of new harmonies, which led to a second, more sophisticated strain of expression through their piano writing. Ginastera is among the most original in this regard, but Paris was a beacon and a portal to the cosmopolitan musical world for Spanish composers starting with Falla, Albéniz, and Grandos.

It could be argued that Debussy, Ravel, and the general impact of Impressionism were important stepping-stones in their development. In songs the main impact comes not in harmonic innovation—melody is the driving force rather than harmonically—but in flashes of keyboard virtuosity. Grünberg, with his extensive experience as both pianist and conductor—he has long associations with the San Francisco Opera and San Francisco Symphony—succeeds in being a strong collaborator, particularly in the interjections of bravura writing that show up, beginning with Obradors’s “Al Amor.”

The main impression one comes away with is that the combination of seductive, vibrant melody and sophisticated piano writing created a kind of golden age for Spanish songs after 1900. Grandos owes his chief fame, for example, to Goyescas, but in the three songs by him that Rayo sings, the piano writing is just as personal. All three are devoted to the sadness of majas, the name applied to young women of fashion who cropped up in the bustling street life of 18th-century Madrid to flirt and fall in love with majos, the young men they met. Rayo beautifully creates the maja’s passionate melancholy, to coin a term, just as she conveys the sultry exoticism of three Canciones negras by Xavier Montsalvatge.

The lusciousness of this recital carries through to the final song, “Estrellita,” by the popular Mexican composer Manuel Ponce. The tenderly loving way that Rayo shapes the song, along with the purity of her tone and the artistry of her delivery, is a perfect example of how classic and popular merge in this repertoire. It doesn’t take away from the enjoyment of this release that it is also an education in the essence of Spanish song.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978