Fanfare

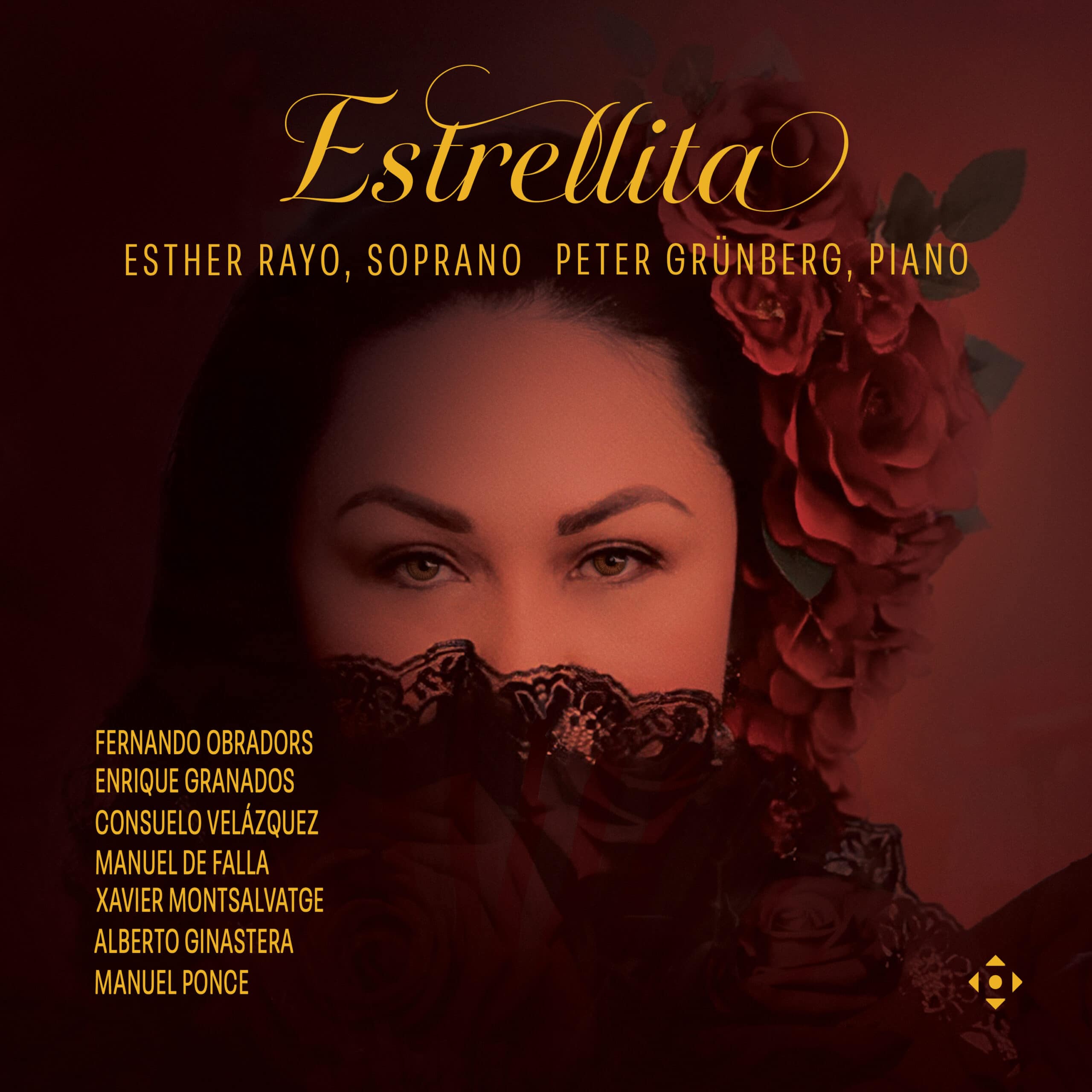

The title of this bewitching album from Esther Rayo and Peter Grünberg comes from Manuel Ponce’s well-known song “Estrellita”, with which it concludes. It’s a perfect choice musically and thematically. All of these compositions have about them that coruscating luminescence of “una estrellita” (“little star”). There are other unifying characteristics: all are by composers from Spanish speaking countries; all have a sense of tradition; and all speak with the colorful and thrilling contemporary harmonic language of the early to mid-twentieth century.

Manuel Obradors showed his profound debt to the past in his Canciones clásicas españolas which sets traditional Spanish poetry going back a number of centuries. Rayo and Grünberg begin their recital with a selection of six songs from the seven books of Canciones Obradors produced. And what a beginning! “La mi sola” starts off with the shortest of flourishes on the piano before we hear Rayo, unaccompanied, singing the first lines of Juan Ponce’s medieval poem “La mi sola”, “my one and only”. In those few seconds of music we’re at once aware of a very special voice, lyrical, sensitive, and mesmerizing. As the group of songs proceeds we’re aware too, that like of all the composers on the disc, Obradors writes for the piano as interestingly as he does for the voice. Take “Al amor”, for example, rendered beautifully by Grünberg, where the piano suggests the torrent of kisses, “besos sin cuento”, Rayo is singing of. Equally the arpeggiated piano figuration in “Del cabello más sutil”, provides not just an accompaniment but another dimension to the voluptuous melody floated by Rayo.

Although he is perhaps best generally known as a composer of piano music, Enrique Granados, was an accomplished writer of song, as his 12 tonadillas en estilo antiguo demonstrate. Rayo and Grünberg give us three of them, all entitled “La maja dolorosa” (“the sorrowful woman”. These portray the responses of three women to the death of their husbands, or lovers. The first is truly operatic (indeed, there is an orchestral version) where Rayo effortlessly navigates the challenging and highly dramatic vocal part. The second, a brilliantly imaginative setting of the woman’s dream, in which her lover lives, where she is brought back to reality with a jolt by an echo in the piano of a phrase that concludes the vivid first song. The third has a dignity about it superbly captured by Rayo, whose voice here has real nobility. Grünberg’s piano playing has a deceptive simplicity to it, suggesting the strings of a guitar or mandolin.

In the most perfect set of juxtapositions, Grünberg then gives us an opalescent rendition of “Quejas, o la maja y el ruiseñor”, the fourth movement of Granados’s Goyescas, his suite of piano pieces inspired by the paintings of Goya. It serves as a fascinating variation on the preceding songs in that when Granados later chose to expand his piano pieces into an opera, the aria which this piano piece becomes is concerned with depicting a woman’s sleepless night before her lover fights a duel at dawn. It’s a great piece of programming, the more so because the piece that follows it by Consuelo Velázquez is a reply to “Quejas”. Astonishingly Velázquez was only 16 when she wrote it, using the same first five notes as those in “Quejas”. Rayo captures brilliantly the mercurial nature of both the writing and protagonist in Grünberg’s arrangement.

The six selections from Manuel de Falla’s Siete canciones populares which follow are a delight. Deeply idiomatic, varied and characterful, they are inhabited with flair and feeling by Rayo and Grünberg, taking us from region to region and mood to mood in what feels like the most immersive of travelogues. The contrast and transitions between the last three in particular is wonderfully achieved where we move from love song in “Jota” to lullaby, “Nana”, to a quite different love song, “Polo”, with magical facility.

Less familiar but equally beguiling is the selection from the Cinco canciones negras of Xavier Montsalvatge. Written just over 30 years after the de Falla, these songs play with the mixture of musical influences experienced in the Caribbean islands. The distinctive rhythm of the habanera pervades “Cuba dentro de un piano”, a lazily nostalgic evocation of the old Cuba, and also “Canción de cuna para dormir a un Negrito”, a beautiful lullaby, one of Montsalvatge’s best known compositions. In contrast, the setting of Nicolas Guillén’s “Chévere” has a disturbing modernistic sharpness to it, brilliantly echoing its startling opening, “The dandy of the knife thrust/himself becomes a knife”, so the listener can never settle. Another distinctive dance, the rumba, fuels the final song “Canto Negro”. Rayo and Grünberg again show themselves perfectly attuned to Montsalvatge’s virtuosic collage. I was particularly taken with Rayo’s appropriately affectless performance of “Chévere”, and the sheer exuberance with which the pair tackle “Canto Negro” is transportive. My only slight regret is the absence of the second song in the collection. “Punto de Habanera”. Having four of the five performed so memorably makes me very much wish it had been included.

Alberto Ginastera’s Cinco canciones populares argentinas are contemporaneous with the Montsalvatge selection. These folk-inflected songs have an obvious place in a recital such as this, but more obviously show musical mid-century influences than Montsalvatge does. I hear Bartók particularly in some of the more dissonant harmonies and the uncluttered texture that Ginastera seeks, although the Spanish/Latin-American idiom is still absolutely to the fore. The use of cross-rhythms in some of the songs is also of course a Bartókian device and Grünberg provides a masterful and self-effacing realization of the brilliant use to which Ginastera puts them in “Chacarera”, the first song of the set and “Gato”, with which it concludes. Rayo too is wonderful throughout, my particular favorite of the set being her unsentimental interpretation of the lullaby “Arrorró”. In his excellent liner notes Grünberg recounts touchingly his own meeting as a young man with Ginastera. I’ve no doubt the composer would resoundingly approve of these performances.

So to Ponce’s “Estrellita”, which Grünberg affectionally and accurately describes as an “evergreen”. Evergreen or not, there is a winsomeness and vitality to the performance here, typical of the approach throughout, which makes it sound as fresh as when it was first heard in Mexico City in 1912. It’s the best possible way to end one of the best song recitals in recent memory, as enjoyable as it is revelatory.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978