Fanfare

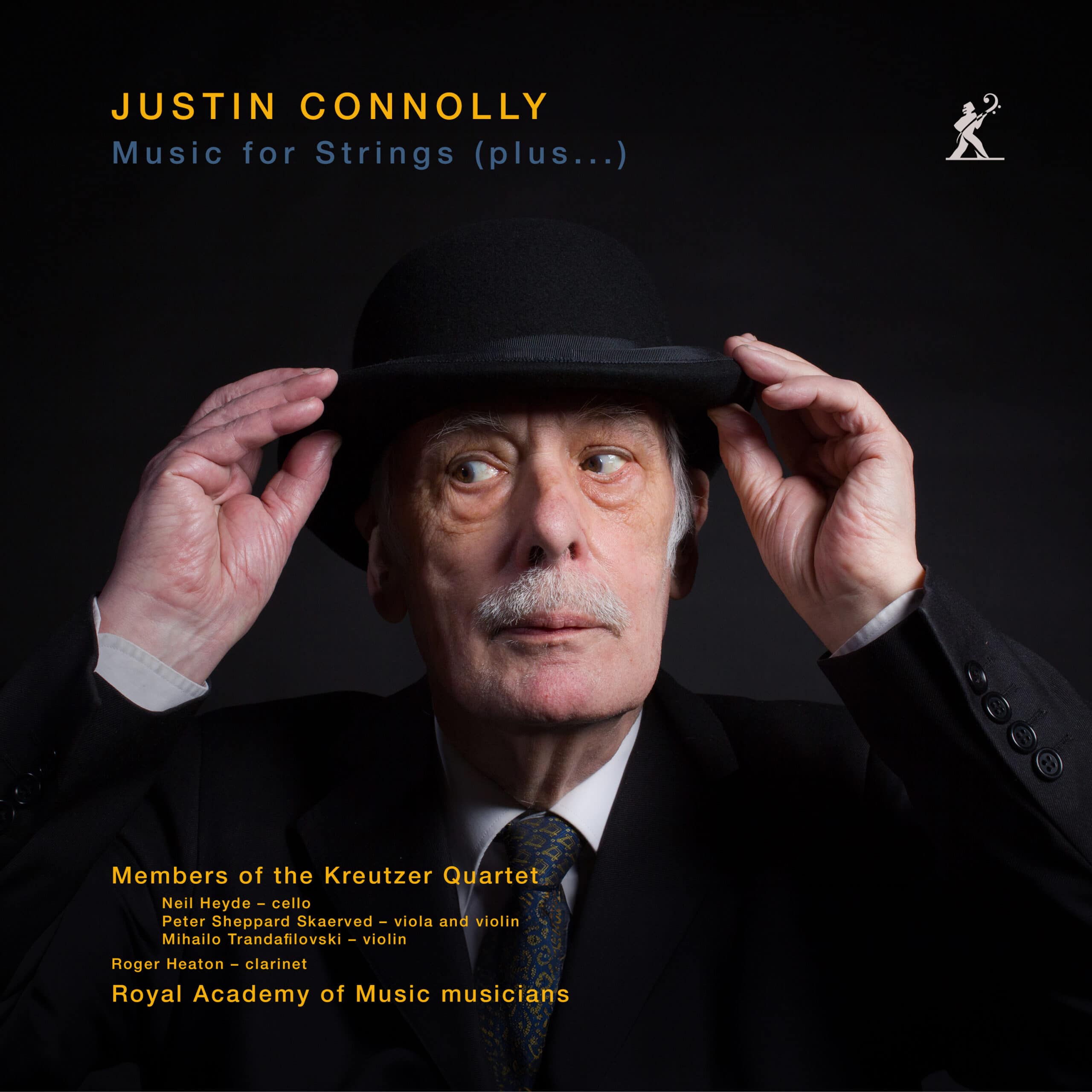

Way back in 1999 (Fanfare 22:6, to be exact), Stephen Ellis bemoaned the absence of works by Justin Connolly in his collection. He will be delighted at this twofer. Connolly was born in London, UK, in 1933. He studied composition with Fricker, while enjoying contact also with Roberto Gerhard.

The op. 43 String Trio features Mihailo Trandafilovski on violin, Peter Sheppard Skærved on viola, and Neil Heyde on cello. Written in 2009/10, it sets out of the stall dissonant, uncompromising. The nature of a string trio against a string quartet, that of competition, gains collaboration and is the basis of Connolly’s writing here. He uses the viola as a structural articulator often: it is the viola that begins sections, taking the lead. This was Connolly’s last major work and he never got to hear it (Connolly died in 2020). The premiere took place by the present performers at London’s Royal Academy of Music in February 2024. While the first movement generates tension through its difficulty for both listener and players, there is a pronounced, albeit angular, lyricism to the central Calmo ed espressivo; the three members of the Kreutzer Quartet play absolutely as equals. The finale, Presto, Vigoroso, Largamente, balances the opening movement’s Vivo ed energico, but in a slightly different form, with the energy like a coiled spring at lower dynamics. The finale’s Largamente offers something of a lament.

The piece entitled Tesserae C, with its designation of op. 16/III, was written in 1971 for Ralph Kirshbaum. It uses a hymn by Parry usually called Repton (Dear Lord and Father of mankind). Parry and Connolly are worlds apart, and as the booklet notes suggest, the theme is used in the manner of a medieval tenor, “as the generator of particular musical events.” With the music’s rasping beginning, we are indeed galaxies away from Parry’s reassuring hymn. There are five movements, a fairly extended Intrada in which cellist Neil Heyde is completely gripping throughout, his assurance total; a scampering Presto con sordina with pizzicato that positively pops; and an Alla sarabanda in which a ghostly shape of the time-honored dance is audible from time to time. It is balanced by an Alla burlesca (and how Heyde’s perfect tuning allows the music to speak …) before an expressive Ripresa seems to reach back to the work’s Intrada.

Both of those works were recorded on 4/3/2024; on July 1 of that year came Triad V, op. 19, with only one member of the Kreutzer Quartet (Heyde) plus Emily Su on violin, and Dmytro Fonariuk on clarinet. This piece was originally written for the Nash Ensemble and commissioned by Birmingham University (UK). The executants at the premiere were the impressive lineup of Antony Pay, clarinet, Jürgen Hess, violin, and Jennifer Ward-Clarke, cello. There are three movements, which the composer suggests are three views of the same event. The music glistens: this is a performance of impeccable taste, plus deep comprehension of Connolly’s intent. The central movement, Risoluto, piuttosto brusco, seems defined by a composed brusqueness, and yet holds a prismatic beauty. Connolly’s choice of simultaneity is a vital part of this: his pitch-class material seems perfectly consistent and, once one acclimatizes, contains all the purity of the purest C-Major triad. The return to the mood of the first movement for the finale, Come prima, is stealthily managed by Connolly in the first instance, but also by the players.

The present recording is an attempt at a reconstruction of Gymel B (1995) via available materials left by the composer. The piece was not quite unfinished, but was rather “overfinished” as the composer was undergoing a revision of the piece that left several systems missing at the end. “Gymel” is an old English term for duet (from the Latin letter for “twin”). Here the “twins” are clarinet and cello. The subtitle is, “deliberately enigmatic,” according to the album notes: “… on Planet X with CN.” The initials, CN, refer to Conlon Nancarrow, and this is an “affectionate tribute” to that composer’s remarkable studies for player piano. Nancarrow also wrote a Study X which is two-voiced: as the booklet notes put it, “rather like Scarlatti relived in terms of Varèse.” There is something of Nancarrow’s composed hedonism in Connolly’s score. Roger Heaton is an astonishingly talented clarinetist; Heyde is the same on cello, and a known quantity. Together, the sparks fly, and at speed in the second part, Concitato. There seems to be some anger present in the third part (Vivace) before the final part, Scherzando, Concitato, which for all of its disjunct intervals, seems somehow calmer.

The title of the four-violin piece Ceilidh, op. 29/I, means “a visit” in Gaelic and refers to a form of music-making in which the violin most often plays a dominant role. There are speculative spear-clashing elements in the ancient history of this practice, hence the title of the second section, Dordfiansa (spear-clashing dance), with the clashes graphically depicted in the music; the depiction of Night in the next section offers appropriate contrast. The performance is superb; some might find the recording just a touch too close. The final section Four-hand Reel offers more of those graphic descriptions in sound.

Scored for solo viola, here Peter Sheppard Skærved, the Celebratio, op. 29/IV finds Connolly at his most approachable. Cantabile is at the heart of this piece; Sheppard Skærved is as confident on the viola as he is on the violin. The shape of the piece is an arch-form first movement, a more abrasive scherzo, and a finale that incorporates elements of both of the first two movements. The performance seems the perfect reflection of Connolly’s form and processes.

Heyde plays the 1995 piece Collana (Necklace) with infinite ease. The sequence of 15 short movements alternates recitatives—the “string” of the necklace—with the more melodic “beads.” Heyde’s placing of notes is a marvel. Here is contemporary music played by a major interpreter; his core sound, too, is just so rich.

We had the Celebratio for solo viola, but then we also have the Celebratio super Ter in lyris Leo, op. 29/II for three violas (Sheppard Skærved, Adonis Lau, and Andrea Fages Saiz) and accordion (Alisa Siliņa). There is a different type of lyricism from Collana here, more lit from within. The pitch materials come from an anagram of the name Lionel Tertis (the influential viola player). The subtitle means “the lion is thrice present in the instruments.” Connolly treats the three violas as one group and the accordion as another “group”; they are independent of each other. I love the way Connolly explains this: “The difference between these two kinds of music is as great as that between the name and the anagram” and goes on to explain that it is the relation between them that determines the form of the work. Aching expressivity sums up this piece: the viola lines, given by three equally strong players here (Skærved, Adonis Lau, and Andrea Fages Saiz) live in high post-Expressionism. Should one edit out sniffs? There is at least one obvious one that will, to quote the hackneyed old reviewers’ maxim, “chafe on repeated listening,” but what a piece! Celebratio super Ter in lyris Leo seems to hold all that is good and soul nourishing about Connolly’s music.

There is a “bonus recording”: four of the five movements of Tesserae E, op. 15/V. All the other recordings date from 2024; this is from September 1983. Another piece based on Repton (see Tesserae C), the original melody sort of “overlooks” the music, in a way that it is not really audible, but determines the pitches via manipulation. On this recording, there are four movements, Capriccio; Melodia I; Serenata; Melodia II (recitativo interrotto). The fifth movement, The Dream of Monostatos, is omitted. The registral distance between flute and double bass is well exploited: Nancy Turetzky plays flute with a wonderful silvery sound; Bertram Turetzky is clearly a virtuoso double bassist, as every melodic detail is audible and in tune.

The booklet notes are detailed, and include a personal reflection of Connolly by Neil Heyde. The subtitle of the disc is “Music for Strings (plus …)” and in a sense that “plus” has multiple meanings. This music is so rich, so rewarding; performances are unwaveringly assured. The musicians that are not the Kreutzer Quartet and Roger Heaton are from London’s Royal Academy of Music. A superb release.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

We noticed you're visiting from Latvia. We've updated our prices to Euro for your shopping convenience. Use Pound sterling instead. Dismiss