Groove Back

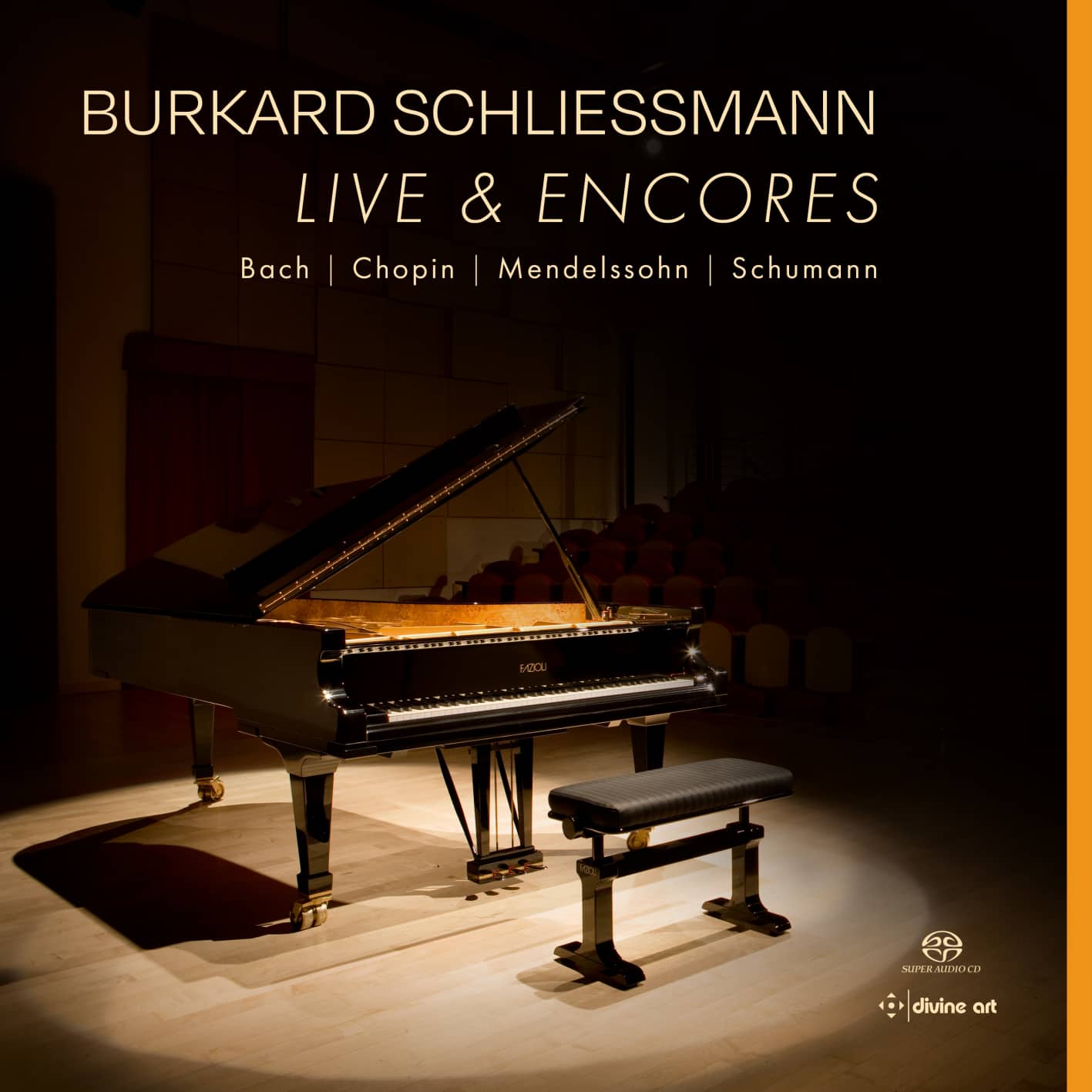

A double SACD of the English record label Divine Art published a few months ago allows us to get to know a German pianist, Burkard Schliessmann, among the best and most interesting internationally in the last decades, given that in our country his name still circulates almost exclusively among piano music enthusiasts alone. These two SACDs were recorded live between April 3 and 5, 2023, when the pianist from Aschaffenburg held two concerts at the Fazioli Concert Hall in Sacile, performing pages by Bach, Chopin, Mendelssohn and Schumann, then fielding an interpretative compendium with a precise common thread, which can be summarized in the concept of the emergence, through the Kantor, and the progressive realization of the tonal language and its supreme piano affirmation through that triad of romantic geniuses, as the same Bavarian wanted to highlight in the accompanying notes in the libretto in three languages (of course there is no interpreter Italian) housed in the elegant box.

The shop of songs presented during these concerts in Sacile is extremely interesting and decidedly challenging: in the order of the playlist of the two SACD we have respectively by Bach the Partita n. 2 in C minor, BWV 826, the Concerto Italiano, BWV 971 and the Chromatic Fantasy and Fuga in D minor, BWV 903, while by Mendelssohn Schliessmann presents a little-frequented piece, namely the nineteen Variations seriouss, Op. 54, which lead to the conclusion of the first album; in the second, instead, we have the Fantasia in C major, Op. 17 by Schumann and the Valzer in D disis minor, Op. 64 n. 2 by Chopin, with the addition of two encores, both still by Schumann, the twelfth piece of Carnaval, Op. 9, entitled Chopin, and the third of the eight Fantasiestücke, Op. 12, namely Warum? (for a total duration of the two SACDs of almost ninety-four minutes).

What should be meant by “match”? Well, at the time of the Kantor this term, which was originally used for a series of variations performed over a bass, was now completely analogous to that of “suite”; therefore, it indicated a series of dances introduced by a piece of an improvisative character that, in the six for Bach’s harpsichord, is from time to time called prelude, symphony, overture, fantasy, praeambulum, touched. The first game dates back to 1726 and from that moment the great genius of Eisenach composed one every year, to be precise on the occasion of the publishers’ fair that took place annually in Leipzig. Thus, in 1731 he gathered the six written games and published them as the first part of the so-called Klavierübung. The overture that opens the second game consists, after the introductory agreement, on which there is the indication “serious”, of some adagio lines. A allemanda, a current, a sarabanda and a rondeau follow. The last time, defined by Bach Capriccio, is really special. The choice of this title is given by the fact that it is a piece freed from the usual formal constraints and is made up of two parts, both repeated twice, with the imaginative theme of the first that reappears brilliantly overturned at the beginning of the second.

Another amazing masterpiece is the Italian Concerto, in which Bach used the two harpsichord manuals to create a series of contrasts, clearly alluding to the type of compositional process developed by Antonio Vivaldi, as in the case of the refrain theme that is treated in a contrapuntal way. Taking inspiration from the title of the piece, it can well be said that the composition as a whole takes on the meaning of a keyboard reduction of an authentic orchestral work. The Fantasy and Chromatic Escape, probably composed in the years that Bach spent in Cöthen from 1717 to 1723, is a visionary work to say the least that looks far beyond its era in terms of formal construction, structure, character and musical language.

At the interpretative level, Burkard Schliessmann proves to be an atypical German artist, in the sense that his Bach is neither obsessively analytical, nor anchored to an executive dimension linked exclusively to the undeniable theological patina that this music expresses, but if anything devoted to a vision that is closer to a Mediterranean esprit because of a passionate shock that feverishly crosses his reading, without, however, ever losing that indispensable discipline of touch and the relative dominance of the keyboard. Let’s be clear, with this I don’t mean that his is a “romantic” Bach, but it is certainly impregnated with a sound beauty, of a timbre nobility that makes the music of the Kantor flow with an accentuated sense of purity, a shiny crystal that shines from the first to the last note, as can be seen from how he faces the Partita n. 2. In addition, the ability to grace the rhythmic process of the Italian Concerto, playing and inserting subtle timbre nuances with the precise purpose of highlighting his melodic côté (therefore, Italian) of the work, almost transforming it into an operatic air, that is, exalting its “singability”, not to mention how the Bavarian pianist manages to transmit the ribs of clear Venetian matrix that run through the wonderful Andante, without the expressive tension decaying into mere and inappropriate sentimentality. On the contrary, in the Chromatic Fantasy Schliessmann proposes, if he succeeds, to bring out the brilliant harmonic dimension of the song through an expressive clarity that never loses the drama of the piano gesture, involving the listener in this continuous and exhilarating ascent, in which the melodic development is the climbing stick.

A necessary premise must be made on Mendelssohn’s piece, the Variations sérieuses op. 54; composed in 1842, which from their appearance were considered one of the most virtuoso works of piano literature of the time, capable of masterfully showing the range of the supreme piano technique through the process of variation. This is because each variation, in op. 54, is based on the other and develops from the harmonic and melodic energies of the previous variation, a sort of brilliant anticipation of what will be the so-called “variation in development” matured by Arnold Schönberg. The very title of the Mendelssohnian page, somewhat unusual at the time, should be understood and interpreted as a precise reaction by the Hamburg composer to an acquired and consolidated musical practice of his time, the one that imposed, in a certain sense, the creation of Variations brillantes, that is to say purely virtuoso fantasies on fashionable themes, often taken from operatic arias. On the contrary, with his op. 54, Mendelssohn presented a work that on the one hand seems oriented towards Beethoven’s Variations in C minor and, on the other, able to anticipate Brahms’ subsequent style of virtuoso variation, in particular the Paganine Variations.

In reading this mid-nineteenth-century piano masterpiece, Schliessmann demonstrates not only that he perfectly dominates the keyboard, shaping the sound matter imbued with an amazing technical difficulty, but also manages to express its moving musicality; the interpretative ability lies precisely in this: to return to the benefit of the listener those expressive tensions, in the alternation and development between slow and fast variations, which permeate the entire architectural arca of the work. After all, the Bavarian pianist decodes the structure, makes it accessible through a heartfelt exploratory alternation of the keyboard, bringing to the surface the shadows and lights that distinguish these variations.

In the second disc, Schliessmann further focuses his concertistic course within the harmonic development, inevitably landing at Robert Schumann, whose work is here represented by Fantasia in C major, Op. 17, together with the two encores, namely the twelfth piece of Carnaval, Op. 9, entitled Chopin, and the third of the eight Fantasiestücke, Op. 12, namely Warum?, and to Fryderyk Chopin with the Waltz in C minor, Op. 64 n. 2. As for the Zwickau composer, the Bavarian interpreter rightly points out that Schumannian music represents a staple for two distinct reasons: the first is that his compositional inventiveness took him far beyond the harmonic progressions known up to his time, while the second is given by the fact that, on the wave of the Mendelssohnian Bach Renaissance, Schumann saw in the escapes and canons of the composers of the past a romantic principle. From this, he considered the counterpoint, with its phantasmagoric interweaving of voices, a sort of correspondence between the mysterious relationships between external phenomena and the human soul, between the transcendent and immanent principle, trying, at the same time, to express this correspondence in complex musical terms, concentrating them above all on the keyboard of the beloved piano.

Precisely because of this search for sound application, capable of making the agon between external and inner forces at its best, Schumann had to face a significant problem, that linked to the fact of presenting an adequate musical and intellectual substance within a large-scale piano form, that is, capable of accommodating a complex sound matter both in the harmonic and melodic fields; and there is no doubt that this operation found in Fantasia op.17 his best result, what is rightly considered his most bold and ambitious piano work, in which the brilliant German composer poured all those romantic instances of Germanic imprint already outlined previously through the literary and poetic contribution given by authors such as Schlegel, Novalis, Eichendorff and Jean Paul.

In returning it to the concert venue, Burkard Schliessmann does not let himself be carried away, especially in the famous opening time, by the enthusiasm generated and offered by musical writing, but presents it in a fragmented, distilled way, investing it with the due mutations and psychological peculiarities, shaping with due attention the changing agogic, in a perennial symbolic balance between titanism and victimhood. Triumph of a sentimentality that already prefigures, as the Bavarian interpreter himself rightly notes in the accompanying notes, to the figure of the Wagnerian Tristan; hence a consequent and inescapable problem given by the harmonic matter that fully anticipates that dissonantic sedimentation that will be humus fertile for Richard Wagner. And Schliessmann turns out to be equally convincing even when he unveils the second half in which the young Schumann enters the visionary lesson of the last Beethoven piano, packaging harmonic cunnes capable of touching timbre schizophrenia, bold glists of modernity that only the passage of time allowed us to appreciate and admire rightly.

To conclude the Schumannian chapter linked to this double SACD, as bis the Bavarian interpreter chose two pieces capable of exalting the beauty, the aesthetic carr of his piano touch; so both Chopin and Warum? They are transformed into two diamonds that shine with a timbre light that Schliessmann knows how to dose as needed and that confirm to us that basically this pianist, as was the Supreme Walter Gieseking, is so little “Germanic” at the level of belonging to a piano school, making sure that the so-called “analytical” dimension in facing a given author can always be combined with a proper timbre patina, able to give beauty and feeling. This is perfectly demonstrated by his reading of Chopinian Waltz, which is striking for its “sobbing” phrasing, as if the Bavarian pianist had wanted, more than anything else, to bring out the emotional dimension behind his formal purity. Therefore, a timbre research that behind the aesthetic aspect is not an end in itself, but becomes an instrument to deepen, to dig, to reach the ultimate heart, that is, the pulsating element, the secret engine that makes everything move.

The taking of the live sound was carried out by that guarantor called Matteo Costa, who wanted to highlight both the instrument itself and the spatial dimension in which it was located. The starting point to get everything is given by the dynamics, which even if it does not impress with its energy, it is nevertheless noted for its cleanliness and for a reassuring naturalness. Another parameter that is to be appreciated is that relating to the sound stage, which sees the Fazioli used by Schliessmann reconstructed to a due depth, so that it can also represent the spatial volumetry that is found around it. A lot of depth but, at the same time, also a lot of finesse of the piano’s focus, capable of expressing and radiating a sound that materializes in the surrounding space, a sound that is not lost in the very moment that invades both in terms of amplitude and height. The piano perlage of the German interpreter is expertly re-proposed thanks to the effectiveness of the tonal balance, always perfectly discernible in the separation offered from the medium-grave register of the keyboard and the high one, as well as the detail, although, as already explained, the piano is positioned at a considerable depth, it does not turn out to be deficient in terms of materiality and three-dimensionality.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

We noticed you're visiting from Latvia. We've updated our prices to Euro for your shopping convenience. Use Pound sterling instead. Dismiss