Fanfare

Thank goodness for discs like these: reminders of music that rewards concentration, music that asks something of the listener (and the performer).

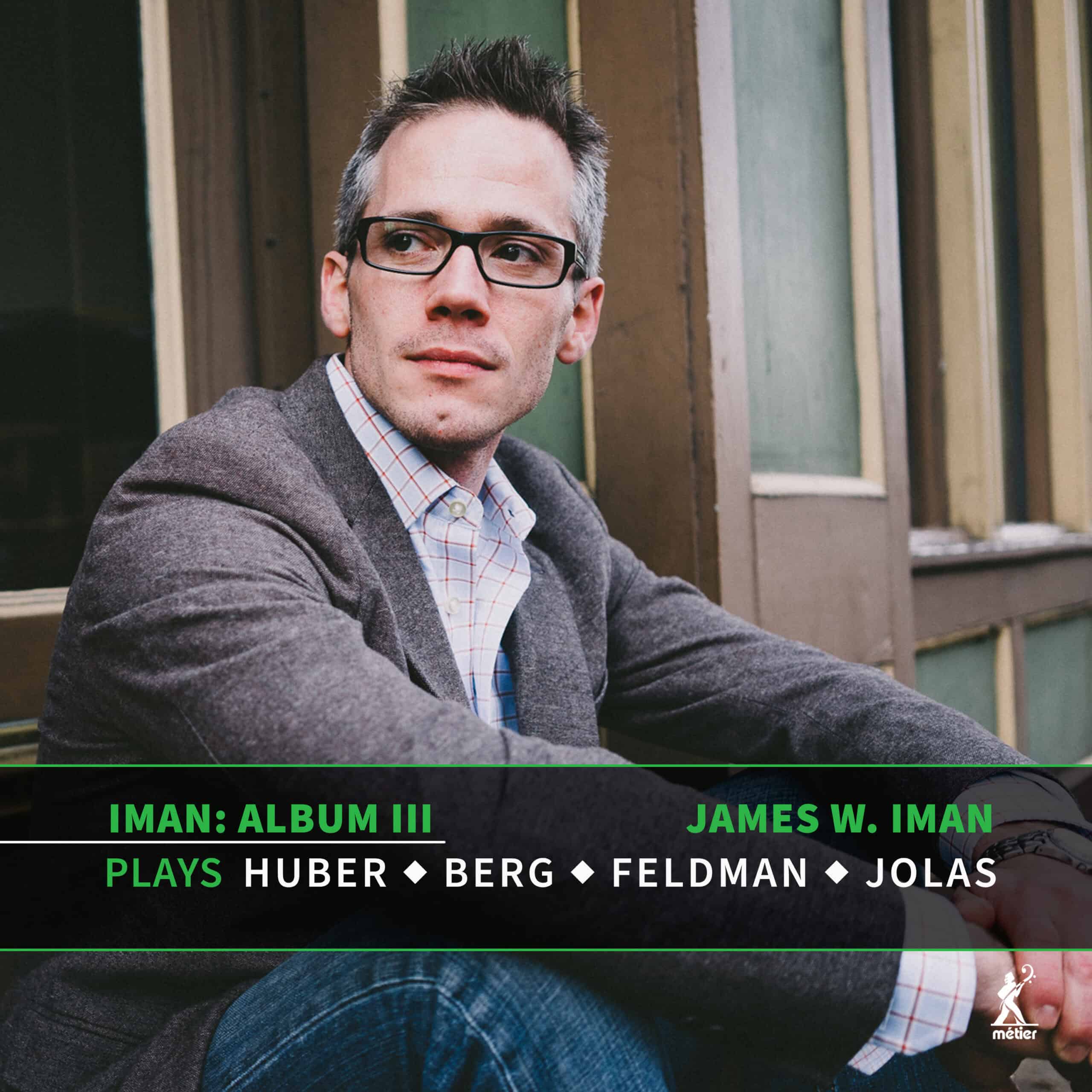

This is the third in James W. Iman’s series of discs for Métier. It was one of many COVID babies. Volume One was reviewed in Fanfare 38:4 by James H. North. The four pieces on the third volume do not form an arc; instead they intersect, creating inter-work webs of communication, parallels and moments of illumination, which one experiences via the act of listening.

The first piece is by Klaus Huber (1924–2017): Ein Hauch von Unzeit II. (“A Breath of Non-Time” is the translation in Paul Rapoport’s review of Kolbein Bjarnsson’s disc Implosion, Fanfare 19:4; “A Breath of the Untimely” is that in Métier’s documentation.) Huber taught Brian Ferneyhough, Toshio Hosokawa, and Kaija Saariaho, all far more famous (or infamous, to some) composers. Some readers may know, however, a brilliant disc of Huber’s music on the Timpani label of orchestral and chamber works with the Luxembourg Philharmonic, including the intriguingly named James Joyce Chamber Music. The piano version of Ein Hauch was written simultaneously with the flute version above. The piece is influenced by and quotes “Dido’s Lament,” although perhaps do not expect to be able to sing along. The piece features a propensity of single lines and many silences, which rather than hold tension simply hold the music until the next note, so the whole appears on one level of calm. This requires maximal control from the pianist, and Iman certainly has that. Strikingly, we are not a million miles from the works of Morton Feldman.But first, we have the Sonata “in” B Minor, Alban Berg’s op. 1. It might be Berg’s first published opus, but it was preceded by a raft of songs; he was no mere greenhorn. Berg’s Piano Sonata is tightly organized, with the thematically led counterpoint leading the listener a long way from B Minor, which is more of an anchor than a harmonic home key approached directionally. Iman conveys the post- Scriabinesque headiness well. He takes his time to relish the motivic correspondences and echoes, something which allows Berg’s harmonies to resonate more than usual. Certainly, there is a plethora of fine recordings of this work, from Uchida to Aimard, and not forgetting Brendel, but Iman’s is one of the most interesting. There is a caveat: The climax of the piece does not quite rise to spectacular heights in Iman’s reading, and I remain convinced that Iman’s X-ray approach is not irreconcilable with fervid passion. That said, the sense of a post-climax processional is a fascinating take here. And, towards the end, there is a palpable fragility, a sense the music might dissolve back into the music of Huber, or indeed into that of Feldman. Pretty much any Feldman work demands an adjusted listening strategy. While the title “Last Pieces” might imply a valediction to composition, they actually date from 1959. As the booklet notes say, “These pieces are formless, there is nothing to remember here—no reminiscing to be done.” And so it is that the music seems to float, disembodied, and yet it carries the listener away. It takes a special type of understanding to interpret Feldman, and Iman has it. These are short pieces by anyone’s standards, let alone Feldman’s (around 20 minutes for all four in this performance) and there is a regret that we do not get another few hours. I jest, but only a little. Here lies repose: the occupying of a pitch space without directionality, without hurry—bliss, some might say. I would encourage exploration of other takes on Feldman’s score: Schleiermacher has unsurprisingly put one down, but one unexpected entrant is the massively talented Cédric Tiberghien, on his Harmonia Mundi album Variations in a performance of riveting concentration.

Finally, there comes a composer whose time has not yet come: Betsy Jolas (b. 1926), who studied with both Milhaud and Messiaen. Her B for Sonata spreads over 21 minutes. There are, like the Feldman, performer decisions to be made, for example as to numbers of repetitions. The music is more active than Feldman, and yet it has the same sense of infinite space. The music in Iman’s hands swirls headily. Underlying all of this is a tone row. A concentration on line from the pianist harkens back to Huber; constellations of notes open out the envelope. Iman’s playing is fabulously sensitive to the power of particular intervals, and to the magnificence of the piece itself. Although the piece is not structural in the traditional tonal sense, Iman still manages to imply that he holds a large picture while presenting foreground filigree. The overarching impression of Iman’s performance of Jolas’ piece, one which could be applied to any of the works on this disc, is integrity. Jolas could hardly ask for a finer performer. There is an alternative, though. Géraldine Dutroncy’s performance of B for Sonata on the Editions Hortus label knocks four minutes off Iman’s duration, and actually there is more of a sense of movement in the more texturally replete moments, offering slightly more varied terrain. This is more of an alternative reading rather than something which is better or worse. But her recording is rather over-generous, and robs her piano of its attack. The composer is coy about what the “B” stands for in the title: “it stands for [,,,]” is what we get. Bach? Beethoven? Betsy? B (-Minor: that would link nicely not only to Liszt but to the Berg that kicked the whole thing off)? Jolas is still here to tell us, of course, but maybe she won’t. Maybe it is better that she does not.

In an over-consuming world that feeds us “easy” music, recitals like this are surely vital: To remind us of what music is capable of, what musicians are capable of and, as listeners, what we ourselves are capable of. The music enshrined here has the capacity to open up whole new vistas, if we let it. The recording is very fine (it was made in Reichgut Concert Hall, Seton Hill University, Greenburg, USA). Recommended.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978