InfoDad

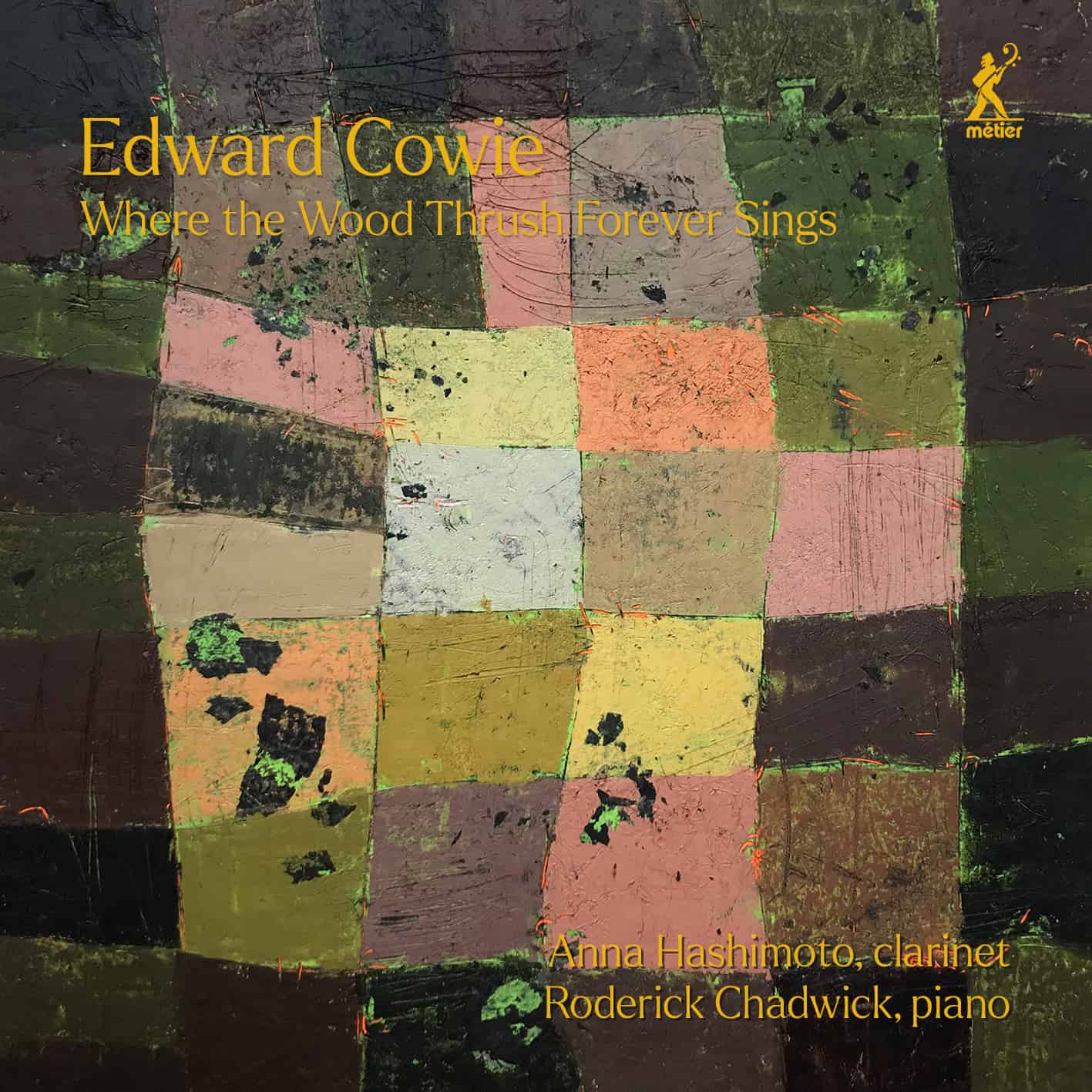

The third Bird Portraits assemblage by Edward Cowie (born 1943) is so sprawling and extensive that it does not fit on a single CD: its 89 minutes require two discs (sold at single-CD price on the Métier label). There are no fewer than 24 works, arranged into four six-piece Books, within Where the Wood Thrush Forever Sings, and only one (the second in Book 1) is actually about the wood thrush. The rest deal with other birds of the Americas – the two prior collections, Bird Portraits and Where Song Was Born, focused on the avian worlds of Great Britain and Australia, respectively. In his new work as in the prior ones, Cowie is at pains to incorporate actual birdsong sounds, not flights of fancy based on them, and thus to bring listeners into close aural contact with the immense variety of sound worlds generated by birds. There is more here, too: Cowie adds to the imitative elements a variety of musical materials drawn from the same geography as the bird sounds, which means that he here includes jazz material, indigenous Native American music, and more. The result is a very long set of brief works (most in the three-to-four-minute range) in which Anna Hashimoto and Roderick Chadwick present self-contained, impressionistic-but-largely-accurate aural portraits of the sounds of the belted kingfisher, greater roadrunner, great horned owl, blue jay, mockingbird, red winged blackbird, Northern cardinal, turkey vulture, bald eagle and many others. There is nothing actually formulaic about Cowie’s portrayals of the birds, but the whole enterprise has a sameness to it that eventually becomes tedious (except perhaps for ardent bird fanciers), since the sonic compass of the two instruments remains the same throughout and the various avian portraits all proceed in more-or-less the same way for more-or-less the same duration. Listeners willing to dedicate considerable time and attention to individual elements of Where the Wood Thrush Forever Sings will find surprises here and there, as in the calls of the broad-tailed and blue-throated hummingbirds, the gentle swaying of the portrayal of the yellow crowned night heron, and the chordal quietude associated with the Virginia rail. In fact, anyone inclined to listen to this music with the same attentiveness that Cowie brought to its creation will find a great deal of diversity of sound and approach within the basic similarity of timing and instrumentation. Most potential audiences, though, will have a far more casual interest than this in the material – and on that basis, this carefully made but highly rarefied bird study will prove very appealing to a very small group of listeners.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=iGIrDXgtiUoQ7kNvwH7LgkG&_nc_oc=AdkSqoPVUG8wvd3sexpiHeU0tK5OcuaopsLQjYkWj5KIcWOcFgpuF1Lu24pXoQJBNymzvpfdP4i5K5kWoz1AqeaJ&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=dsDQva4-waY8FNFibH9H6w&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQFIHcWOu0rEkj3NVLtUMLn6hy2vjefrXI5WgDt9b1-TZuSupIxutdQRcnAMuZspuBaijNO7KXp-1w&oh=00_AfzbfF9hbvU5JxlWU_g1vKMRaa43TbyvGBwCZ8lAfaSaFg&oe=69B41A81)