Atlanta Audio Club

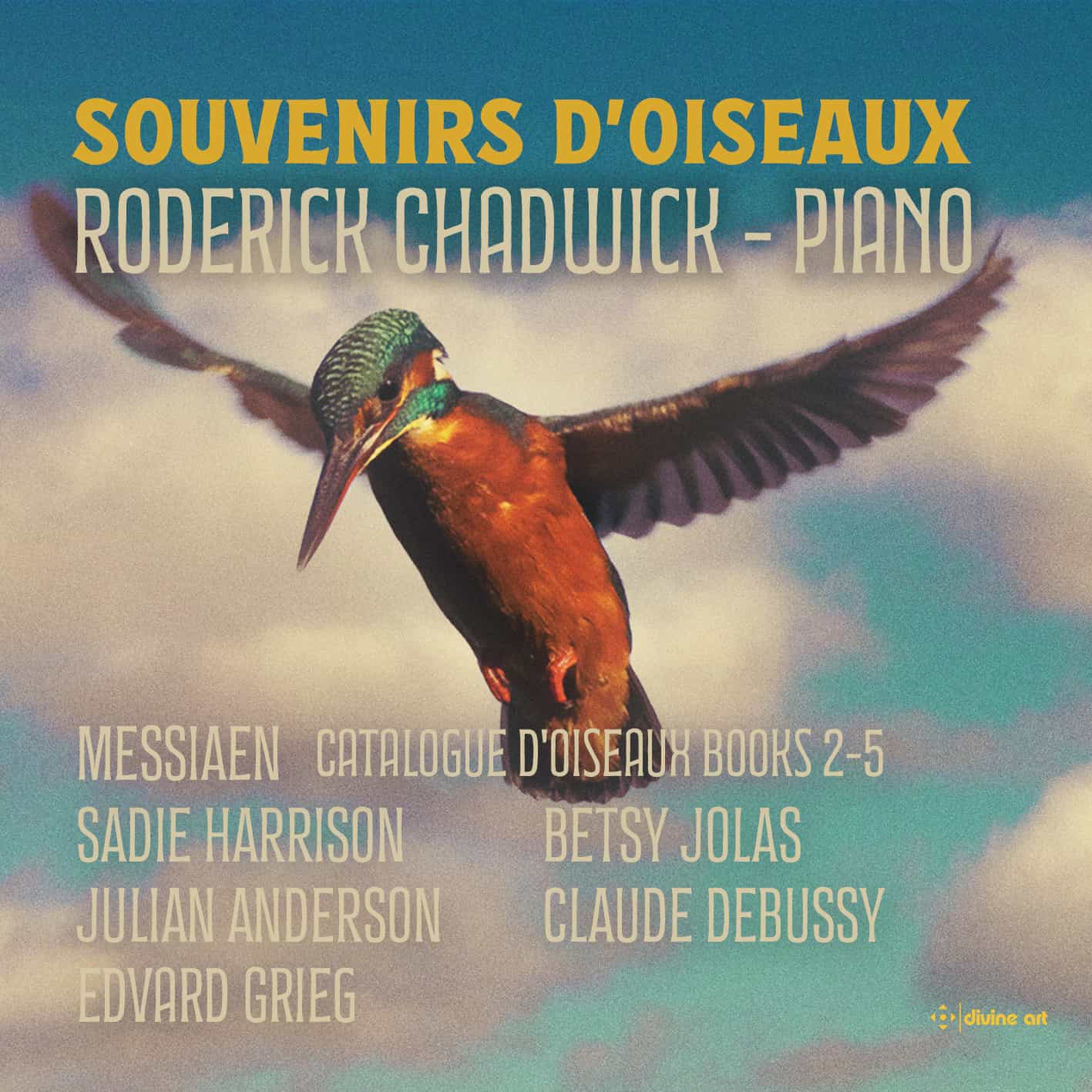

English pianist Roderick Chadwick (b. Manchester 1978) loves nothing more than a musical challenge, and he has consistently found it over the years in the music of Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992). The French composer, in turn, had an abiding interest, virtually amounting to a mania, in birdsong. It all fit in with his innovative use of color and musical time, which gained him the loyalty of a number of students and admirers.

I almost passed on the opportunity to review the present album, consisting of Books 2 – 5 of Messiaen’s Catalogue d’oiseaux. The music is that different from any I’m used to reviewing. In fact, I’m not sure that Catalogue d’oiseaux is not so much music for its own sake as it is the application of musical technique, in the way of harmonic progressions and Messiaen’s unique concept of musical time, to the study of the pitch level and rhythmic precision in the songs of birds, which he seems to have regarded as nature’s primordial singers. This album may, in fact, appeal most keenly to music lovers who also happen to be enthusiastic bird-watchers.

For the sake of space, and ignoring pieces by Messiaen’s students and loyal followers Sadie Harrison, Julian Anderson, and Betsy Jolas, Claude Debussy’s prelude “Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir” and Edvard Grieg’s well-loved Notturno, included for our listening pleasure, as well as the other Messiaen pieces in this album, I’d like to focus on Book 5, No. 4 of Catalogue d’oiseaux. It seems to embody the essence of all Messiaen was striving for. It also reflects the fact that he is said to have experienced the phenomenon of chromesthesia, by means of which musical chords are perceived as colors (no kidding). This piece, subtitled La Bouscarle, (also known as Cetti’s Warbler) is, at a playing time of 11:35, the most fully developed piece in all the Catalogue. It encompasses the variety of sounds one is likely to hear in a marsh on a river in the late afternoon as evening begins to descend, including the seamless flow of the stream whose music transforms into gentle evening sounds. Numerous color impressions which Messiaen would later classify as: yellow, violet purple, lead grey; blueish green, magenta, light pink, red-orange, violet blue, light coffee tending to white, green, gold, and reddish brown, mark the gradual transformation of the day into night, and are contrasted with the characteristic complaint, “brusque and violent,” of the Bouscarle itself.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=aY1NGfNpOoYQ7kNvwH3EIrl&_nc_oc=AdnLZYutXGylf4QGWVOrXooTl9kB_CYzz8RLCO8DiFxUcXPOUtqAy-_4a24sP4MI0n0&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=ob6yWbjMORAiDK8tA-SUVw&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQE8G21hySdfpnDXooMOxgrAbsmP8sknFIw-F6jwO6XQ1gsyEOiz7kA-UNlSNzaKNcuN6XrYlTvkBQ&oh=00_AfzM2UgNY7PnkMz-gUdQXLHp2_l-u8XGgkiY4DRQtb_qGQ&oe=69AD8301)