Fanfare

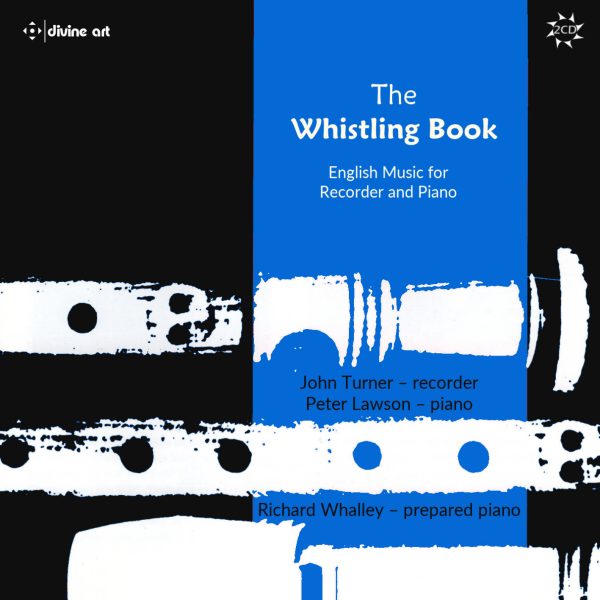

Many of the tracks on this disc originated, I believe, from a compact disc from Forsyth Brothers, a musical instrument and sheet music shop on Manchester’s Deansgate with a long and venerable history. Forsyths holds many fond memories for me, as I was brought up in Manchester and this was my go-to shop. Many years later, I returned to write on their piano stock for a UK journal. This rerelease, then, is a testament to their devotion to and passion for music. It is also testament to John Turner, whose work for the recorder has helped to put contemporary English music for the instrument on the map.

We met the combination of John Turner and composer Nicholas Marshall on a disc entitled Anthony Burgess: The Man and his Music on Métier (Fanfare 37:4, reviewed by myself back in 2014). Now we have a whole two discs of contemporary recorder music, a veritable treasure trove for recorder players. Take Geoffrey Poole’s attractive Skally Skarekrow’s Book, comprising a nicely varied four movements, from the pastoral “Clouds (with silver linings)” to the light waltz “Spring Breezes” (where Peter Lawson gets his moment of glory in the rhythmically skipping Trio). After one 1:19 of languishing in the sun (“Sunshine” is the title of the third movement), the final “Hailstones” delivers a helter-skelter shower of notes. It’s great fun, but amongst all the frivolity is a piece that requires keen communication between the players. Rhythms and motivic interchanges need to be pinpoint; and, indeed, they are everywhere on this release.

The musical language of Mancunian composer Michael Ball’s Prospero’s Music is more advanced. Ball studied with Howells at the Royal College of Music and later, in Siena, with Franco Donatoni. Unafraid to call for extended techniques in Prospero’s Music (originally for recorder and guitar), Ball’s 1984 piece is inspired by The Tempest; the sound of a sea-buoy in the mist on a coastal walk provided the necessary nudge of inspiration. Some of the rhythms are taken from speech rhythms in “Full Fathom Five” (Ariel). There is a scherzo for Ariel, and music depicting the lovers Ferdinand and Miranda. A piano cadenza (with “recorder taunts”) is stunningly delivered by Lawson. While Poole’s piece was the perfect opener, it is good to hear something one can get one’s teeth into. Again, ensemble is impeccable, and there is a wonderful sense of play from Turner, who is also clearly a consummate master of the recorder. The piece is just a smidge under 10 minutes, but my only complaint is that there is not more of it. The ending, though, is beautiful and haunting.

The programming is carefully considered. Light relief is required after Ball’s piece, and Alan Bullard (b. 1947) does the honors with his Recipes, five delightful movements that encompass “Prawn Paella,” “Fish and Chips,” “Special Chop-Suey,” “Coffee and Croissants,” and “Barbecue Blues (when the fire goes out).” As frothy as the presumed cappuccino of the initial “Coffee and Croissants,” this is skillfully written, as is the Gallic-tinged Waltz. The barbecue is clearly a laid-back affair (there is some amusing flutter-tonguing from Turner here). Continuing the national affiliations, “Prawn Paella” arrives as a habanera with a Carmen quote, while there is inevitable pentatonicism in “Special Chop Suey” (an air of mystery does make me wonder what went into the mix, though). The UK’s second national dish, fish and chips (we are told the first is curry) is a circus galop, cheeky and outrageous. It needs a nimble player, and Turner is obviously one such.

Lancashire-born Alan Rawsthorne is probably the most familiar name so far, another Northerner (born in Haslingden, Lancashire in 1905). His Suite was premiered in 1939 and later arranged for viola d’amore and piano. Thought to be lost, Rawsthorne’s Suite resurfaced in 1992, in the viola d’amore version. But the alterations from the recorder version were apparent, and we are blessed to hear a sophisticated piece, particularly its second movement “Fantasia.” Even the concluding “Jig” is no mere vapid romp. This is a fabulous piece.

Born in 1942, Nicholas Marshall taught at Dartington; he also penned two operas. His Caprice is all too brief, but it does breathe the air of carefree contentedness. Against that, Douglas Steele (1910–1999, a successful conductor as well as composer) offers a haunting Song for recorder and piano. It is no surprise to learn this was originally a song for voice and piano. The piece seems to offer solace, ending in distinctly warm mode.

Surrey-born John Addison (1923–1998) is probably best known as a composer of film and television music. Here, we have his Spring Dances, premiered by Turner in 1995. Written for solo recorder, the second of the three movements, an Andante con moto, is rather bland, but the outer movements have more life. Interestingly, Addison’s Wellington Suite has just recently turned up in Fanfare’s reviews (British Piano Concertos on Lyrita, reviewed by Robert Markow in 46:3, Jan/Feb 2023). From the review description, Wellington Suite sounds like a lot of fun; I find it hard to find such joy in Spring Dances, no matter what that title promises, alas.

The music of Robin Walker tends to fuse the traditions of English music with those of India (especially the rhythmic processes of the latter territory). First performed in York Minster by John Turner and the composer, A Book of Song and Dance comprises 11 movements. There’s no missing the composer’ dipping into the repository of English folk music. The fifth movement, “Rite,” is particularly fine, with the spiky piano lines often in contrast to the more lyrical recorder. Just as impressive is Turner’s tuning: When asked to replicate a (very) high piano pitch, Turner is spot-on. Five of the movements include piano; four are for solo recorder; the remaining two are for solo piano (the 20-second, Bartók-brutal “Dance 1” and a short canon that sits next to it). Just as impressive is “Shenandoah,” the familiar tune garlanded by beautiful, dissonant harmonies on piano. Walker’s writing for piano is incredibly imaginative, and very subtle. He has humor, too (witness the final lullaby, “Tired Boy”; you will recognize the tune, beyond doubt).

The final piece on disc one is also by Robin Walker: Her Rapture (2021), written to celebrate composer and teacher Dorothy Pilling. Walker met Pilling only once, and was impressed by an “idiosyncratic charm that seemed to belong to an earlier age.” Later, he found that Pilling was born near his own hometown of Todmorden (in the West Riding of Yorkshire). As he puts it, “the piece … seeks to set down both the delight and the propriety of this remarkable lady.” Scored for solo recorder, it consists of soaring lines and high, exultant gestures. A whole disc of Robin Walker’s works can also be found on Métier, again featuring John Turner in a couple of pieces. This disc was extensively reviewed by David DeBoor Canfield in Fanfare 43:2, who wrote that “the music of Robin Walker is engaging and effectively written, and will provide enjoyment to anyone who will give a listen.” I can only concur.

The second, shorter, disc reveals a similarly eclectic mix of composers, including a piece by Turner himself. Walter Leigh’s Air for recorder and piano acts as an intrada. After studies at Cambridge, Leigh (1905–1942) studied with Hindemith in Berlin. The short Air is his last work (he was killed four days later, serving in World War II as a radio operator in Cairo; his tank received a direct hit). There is, I think, a touch of Hindemith to some of the harmonies here.

Readers may know I am something of a fan of the music of the long-lived Arnold Cooke (1906–2005). Another Hindemith student in Berlin, Cooke left a large corpus of works, including two operas. The Capriccio for recorder and piano (1985) exhibits the spiky playfulness I associate with his music, and his ability to create lyrical spaces utilizing similar harmonies, often with little or no drop in tempo.

Another UK composer with a fascination for Indian music, Anthony Gilbert (b. 1934), has a particular love of the sopranino recorder. His Farings is a set of eight virtuoso pieces (try the unstoppable second, “Eighty for William Alwyn”). Written over a span of some 13 years, the set nevertheless coheres beautifully, and yet each movement is entirely individual. Try contrasting that “Eighty for William Alwyn” with the very next “Arbor Avium Canentium”; the latter is both a tree of singing birds and variations on the initials of composer Arnold Cooke, whom Gilbert refers to as “the gentlest of composers.” I like the concept of the fifth movement, “Slow down after fifty,” partly because maybe that’s what I should have done (but didn’t) and partly for its surely Messiaen-influenced lines and rhythms. A “great lady of Manchester,” Ida Carroll, is the inspiration for “Ida Carroll Her Lullabye”; the title surely is inspired by Dowland and his contemporaries, and the material by the tuning of Carroll’s double bass (apparently called Ebenezer). Gilbert’s playfulness (although never frothy frivolity) is found again in “MidWales Lightwhistle Automatic,” inspired by the shipping forecast (something of an unexplained institution in the United Kingdom; perhaps there is something reassuring about the announcer’s delivery). Finally, “Chant-au-Clair,” for composer David Cox, reflects Cox’s love of plainchant, but in the most skipping way possible. This is a fabulous set of pieces.

The one piece written by Turner himself here is the Four Diversions. There is a full disc of Turner’s music reviewed on the Fanfare Archive, Christmas Card Carols, again on the Divine Art label (regarding which Henry Fogel gave very positive his thoughts in Fanfare 41:4). The Diversions were written in 1968–69 and comprise “Intrada,” “Waltz,” “Aubade,” and “Hornpipe.” Needless to say, all the movements are superbly written for the recorder. The “Hornpipe” is particularly virtuosic in nature, while the third movement “Aubade” is lovely and wistful.

David Ellis’s Shadows in Blue uses sopranino, bass, and tenor recorders. Ellis was at Manchester at the same time as Peter Maxwell Davies, Alexander Goehr, Harrison Birtwistle, Elgar Howarth, and, for what it is worth, my first piano teacher, Robert Marsh. The writing here is fabulous: This is music to get one’s teeth into and offers a plateau of complexity but also highly emotive, profound harmonies. This piece alone is enough to ask for more. There is an opera by Ellis, Crito, which won a Gulbenkian Award and the Morley College Opera Prize; a piano concerto written for none other than the great John Ogdon (who was also at Manchester at that time); and a violin concerto for Martin Milner (co-leader of the Hallé with Pan Hon Lee in my day). Again, Divine Art has previously done sterling service and furnished us with a complete disc of music by Ellis, performed by Mancunian forces and reviewed by Barnaby Rayfield in Fanfare 38:4.

We stay near Manchester (Ashton-under-Lyme) for composer John Golland (1942–1993). A student of Thomas Pitfield, Golland taught at Salford College of Technology (in the Media Studies department). The Divertissement was first performed in its revised version in a concert for the 85th birthday of Pitfield. Three movements have been arranged for horn and piano, a transcription requested by Ifor James. These remain unpublished, so now would be a good time to highlight this; the horn repertoire needs all the help it can get. The four movements of the recorder version are lovely, with the third movement “Air” diving down to surprising depths. The concluding “Gigue” is quite the whirligig. A second piece by Golland is New World Dances (1980); there is also a version for recorder and string orchestra. This is lighter: The initial “Ragtime” is deftly performed by Turner and Lawson, the “Blues” is nice and laid-back, while the concluding “Bossa Nova” shows off Lawson’s repeated notes (a kind of Erlkönig on a hot tin roof), his left-hand dexterity, and of course Turner’s supreme command of his instrument. Fun (there are even some finger clicks, for goodness’ sake) here masks as art, perhaps.

The piece by Richard Whalley (b. 1974, senior lecturer at the University of Manchester) takes us to a very different space. Here, Turner is joined by the composer on prepared piano. Cage is the obvious reference point. The title of his piece here, Kokopelli, refers to a fertility deity of some Native American cultures of the southwestern USA; he is shown in some depictions playing the flute. Of his various affiliations, one is that Kokopelli represents the spirit of music. Written to celebrate Turner’s 70th birthday, the piece was premiered in 2013. Highly atmospheric and with skillful use of both the prepared piano and recorder multiphonics, Kokopelli is a significant addition to the recorder repertoire.

The final, fun piece is Saturday Soundtrack by Kevin Malone (a pupil of Feldman and Bolcom). This is a soundtrack to an imaginary cartoon (there’s a touch of the Marseillaise in there, amongst other snippets). There are also sound effects from the performers (and apparently visual ones in live performance, too), although we are necessarily denied them here. It certainly raises a smile, anyway, and Turner and Lawson throw themselves into the mix with abandon.

This is a massively varied twofer, then, and a testament to Turner’s devotion to and command of his instrument. The recording quality is splendid throughout, mostly taken down in Macclesfield at ASC Studios in October 1988, with the balance recorded at Heaton Moor Studio, Stockport in January 2021, and the Cosmo Rodewald Concert Hall, Manchester University, in June 2017.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978