Fanfare

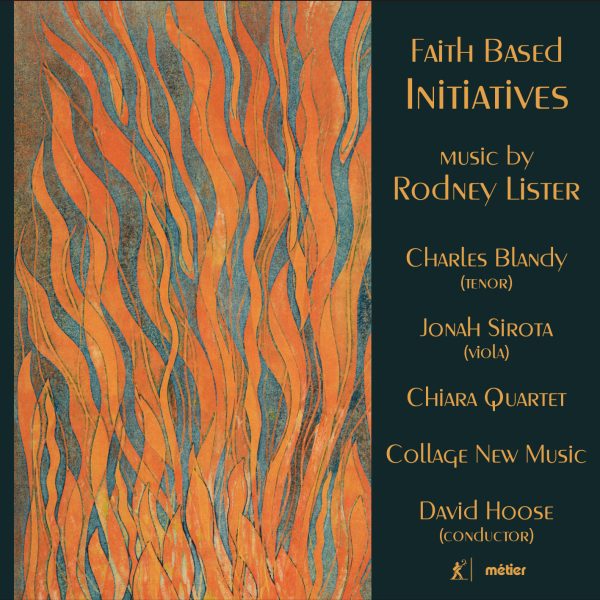

Faith-Based Initiatives presents three works by American composer Rodney Lister (b. 1951). Lister received his early music education in Nashville, TN; later, he studied at the New England Conservatory of Music and Brandeis University, and with Virgil Thompson and Peter Maxwell Davies. Lister is a member of the faculty of the Boston University School of Music and is director of that school’s new music ensemble, Time’s Arrow. He is also on faculty at the Preparatory School of the New England Conservatory. The spirit of Charles Ives may be felt throughout the works on this recording. In his liner notes, Lister makes frequent reference to Ives, and the featured music affirms a powerful bond between the New England composers from different eras. The opening work, Faith-Based Initiative (2004), is scored for string quartet. The title is multi-faceted. Lister explains that the most obvious reference is “to the governmental program which is one of the means by which the Bush administration attempted to obliterate the separation of church and state in the United States.” Lister turns to a hymn frequently used by Ives, Come, Thou Font of Every Blessing. Lister presents the hymn both in its original form, and in permutations far more abstract, both melodically and harmonically. Faith-Based Initiative also fulfills the composer’s wish to explore “the challenge of integrating smoothly and convincingly into one work different tonal languages.” I suspect that all the elements I’ve mentioned will resonate with Charles Ives devotees. And Faith-Based Initiative, a nine-minute piece in one movement (here, beautifully performed by the Chiara Quartet), is a compelling work that stands proudly in the Ives tradition.

So, for that matter, does Complicated Grief (2013-14), a three-movement work for viola solo. Lister once again uses hymns as the work’s foundation; “not the intellectually respectable, almost folk tunes, like From the Sacred Harp, but the poppy, sort of honky-tonk hymn tunes I grew up hearing on TV and radio and sort of love.” Those hymns are: I Come to the Garden Alone (Mvmt. 1), How Great Thou Art (2), I Know Who Holds Tomorrow, Softly and Tenderly Jesus is Calling, and When They Ring Those Golden Bells For You and Me (3). Lister wrote Complicated Grief in response to a request by violist Jonah Sirota, who performs the work on this disc. After Lister began composition, his father died. Lister recalls: “The tunes and working with them intertwined in my mind with a whole raft of thoughts about my life and my relationship with my father, and my feelings about him and his death.” Lister “deconstructs” the hymn melodies, “reducing them to their basic thematic elements and then developing those elements on their own and in various kinds of combinations with the tunes themselves.” The trio of hymns in the finale is presented as a quodlibet, with the melodies intertwining, in different keys, before they reach a harmonic confluence at work’s close. Bach and Ives both would have been pleased, I think. Here, and throughout the work, Complicated Grief poses considerable technical and expressive challenges for the violist, all triumphantly met by Jonah Sirota.

Friendly Fire (2007-12) was inspired by the Ken Burns Civil War documentary television series. Three poems about the Civil War—“Ode to the Confederate Dead” (Allen Tate), “The March Into Virginia” (Herman Melville), and “For the Union Dead” (Robert Lowell)—provide the opening, mid-point, and conclusion of this work, scored for tenor and chamber ensemble. For his setting of the Melville poem, Lister found inspiration in Ives’s song, In Flanders Field. As with Ives, Lister calls upon various other songs (here, relating to the Civil War) as the basis for “The March Into Virginia.” In turn, those Civil War songs, “manipulated in various ways, would then become the source of the settings of the rest of the poems.” And in between the trio of Civil War poems are several others concerning various U.S. wars. While the influence of Charles Ives is once again undeniable, Friendly Fire also invites comparison with Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem (1961). There is a striking thematic/aesthetic sympathy between Lister’s selection and settings of war poems, and Britten’s masterful realization of verse by Wilfred Owen recounting the horrors of World War I. In both cases, those who heroically fight and die in wars do the bidding of more powerful individuals, far removed from the carnage of the battlefield. And by avoiding histrionics in their vocal settings, both Lister and Britten emphasize the narrators’ status as helpless pawns. The protagonists in Friendly Fire and War Requiem well understand both their status and inability to change it. As in the case of Britten’s War Requiem, the vocal and instrumental writing in Friendly Fire is keenly sensitive to the texts, and strikingly expressive. And I must say that in listening to the tenor music in Friendly Fire, I was struck by how well suited it would have been for Peter Pears. But the featured tenor on this recording, Charles Blandy, is marvelous in his own right. Blandy sings the music with the utmost feeling, technical assurance, and attractive tonal quality, and his diction is exquisitely precise and clear. Collage New Music and conductor David Hoose are likewise outstanding in realizing Lister’s colorful and varied score. The recordings, made between 2013-15, provide a first-rate concert acoustic. In addition to the composer’s eloquent program notes, there is a lovely and in-depth appreciation of Lister by Nico Muhly. Blandy also contributes a passionate and convincing argument for retaining Lowell’s use of a vile racist epithet in “For the Union Dead.” I’ve mentioned the influences and elements at play in this Lister compendium. All of them (including honky-tonk!) are of great significance in my musical life. So it’s perhaps not surprising that I found Faith-Based Initiatives a most engaging and rewarding experience. But this is highly accomplished, heartfelt, and expressive music that I believe will appeal to all who gravitate toward contemporary music with a decidedly lyrical orientation. Warmly recommended.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978