Infodad

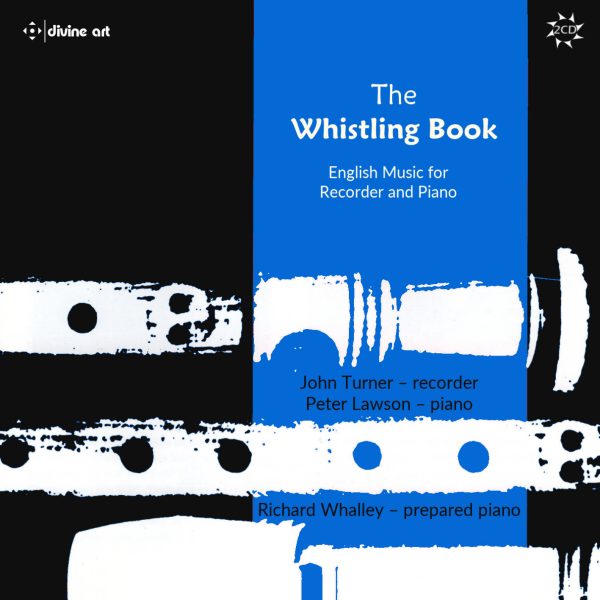

This offering of English music for recorder and piano, like the Prokofiev CD, includes older material and newer, but the motivation of the whole thing is different: it builds on a 1998 release of recorder works and adds to that earlier material both through remastering for improved sound and by the addition of previously unrecorded material. What is heard here will likely be unknown to virtually anyone who does not play the recorder, and even to many people who do. This is therefore an exploratory release that should be of considerable interest to recorder players but will inevitably be somewhat less sanguine for non-performers, given that it offers two full hours of pieces that are all short enough to be encores: some are individual works, some are suites consisting of brief works, but in all cases the material is short and to the point.

Furthermore, the music, although mainly tonal and often danceable and light, is all from the 20th and 21st centuries, resulting in a certain inevitability of sound that is often quite pleasant but tends after a while (that “while” being less than two hours) to wear thin. The composers included on the first disc here are Geoffrey Poole (born 1949), Michael Ball (born 1946), Alan Bullard (born 1947), Alan Rawsthorne (1905-1971), Nicholas Marshall (born 1942), Douglas Steele (1910-1999), John Addison (1929-1998), and Robin Walker (born 1953). Those on the second disc are Walter Leigh (1905-1942), Arnold Cooke (1906-2005), Anthony Gilbert (born 1934), John Turner (born 1943), David Ellis (born 1933), John Golland (1942-1993), Richard Whalley (born 1974), and Kevin Malone (born 1958).

With the exception of Whalley’s Kokopelli, written for prepared piano and performed on that instrument by the composer, all the works use a standard piano to go with the recorder – several different recorders, actually, all played with skill and obvious devotion by John Turner. The admirable way that Turner and pianist Peter Lawson handle these works provides them with as much individuality and differentiation as possible. But even when some composers assemble suites using old-fashioned movement designations (Rawsthorne, Turner, Golland), while others favor more-modern titles for individual sections (Poole, Bullard, Gilbert), and still others contribute single pieces rather than groups of them (Ball, Marshall, Steele, Leigh, Cooke), the fact remains that for most listeners this will be “much of a muchness” of pleasantries of various sorts.

There is a lot to enjoy here in small doses, but the dosage totality is such that the recording seems primarily designed to draw recorder players to recent or fairly recent music of which they are likely unaware, so they can incorporate it into their own practices and recitals.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978