Fanfare

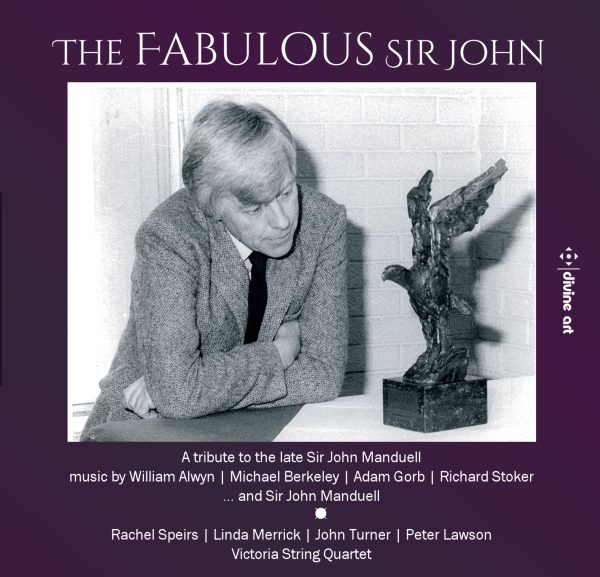

This fine disc is a tribute to the late Sir John Manduell (1928-2017), founding principal of the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester and widely acknowledged Renaissance Man. It is a sequel to Songs for Sir John, also on Divine Art.

The Aria for Sir John by Adam Gorb (b. 1958) is beautiful; soft strings (the excellent Victoria String Quartet) create a bed of sound over which the insuppressible John Turner weaves recorder lines. It is the recorder that “sings” the aria, with strings an active conversation partner. Premiered in 2019 at the University of Manchester, the work is airy and free. It’s no surprise to learn from James V. Maiello’s review of Gorb’s First Symphony that that work is “more like a divertimento than a symphony” (Fanfare 40:4); there is a deft hand at work here.

The Gorb acts as an introduction to music by Manduell himself. First, there comes the eight-minute Elegy for string quartet of 2005. It is dedicated to Christopher Rowland (first violin of the Fitzwilliam String Quartet and a teacher at the Royal Northern). It is a highly impressive piece, firstly for its expressivity but also for its clear, tight pitch organization and equally clear counterpoint. The various aspects combine to create a most moving piece. The string orchestra version (not heard here) was requested and premiered by Kent Nagano, whose thoughts on the piece seem prescient: “I found the work to be a masterpiece—one of Sir John’s best. A work firmly anchored in the future yet written in a way that one heard the past—one recognizes the universality of humanism.” Those words about the future ring true in the grittiness of some of the chords, almost rasping in this performance.

The texture thins for Recitative and Aria, performed here by Benedict Holland and Kim Becker. It was written in memory of Peter Crossley-Holland (a colleague of Manduell’s at the BBC), and Manduell used the two salient letters of the dedicatee’s surname as a starting point. The mode of expression is simpler than in the Elegy, the 11/8 “Aria” dances and skips rather than confuses. This is a sterling performance; tuning (no doubt problematic in some of the writing) is superb throughout, and the recording is perfectly balanced.

One of Manduell’s earliest works, the charming Trois Chansons de la Renaissance dates from 1956, when he was a student of Lennox Berkeley at the Royal Academy of Music in London. It’s probably no accident that Lennox’s own first published work was a setting of the same du Bellay poem that comprises the second movement. But first there comes an utterly compelling and delightful setting of some Ronsard, “Mignonne, allons voir si la rose” (texts are included, but not translations—not relevant in the case of the Alwyn, of course). The second is that du Bellay setting of “D’un vanneur de blé aux vents.” It is here that soprano Rachel Speirs comes into her own, teasingly playful, her light soprano perfect for the fragranced music, invoking late-summer haze as a thresher gets on with his work. Finally, we have “A sa dame malade,” a setting of Marot (which, like the Ronsard, begins with an invocation of “Mignonne”). There is wit in this last setting, which is about the dangers of “gastronomic self-indulgence”; perhaps I need to listen to this on repeat.

Using treble and descant recorders, John Turner gives a compelling account of Bell Birds from Nelson, written for the 70th birthday of composer Anthony Gilbert. I confess, with all of the Manchester-centric music, I had imagined Nelson to be the place in Lancashire (in the borough of Pendle); but no, this one is in New Zealand (Gilbert was an Ozophile). The programming, like Turner’s playing, is perfect; the single line ending of Bell Birds from Nelson segues into the solo clarinet which opens Nocturne and Scherzo (for clarinet and string trio), premiered in 1968. It is Manduell’s harmonic awareness that is so striking here; the construction of the chords is managed by a super-acute ear. While the reference to Bartók Night Music for the Nocturne stands, it is slightly misleading in that Manduell’s vocabulary is absolutely distinct from Bartók’s (and, possibly a rather controversial statement, arguably preferable). The lead-in to the Scherzo is delicious, a lovely clarinet slide that is to return later (beautifully managed, as are the angularities of Manduell’s writing in the Scherzo proper). There is beauty everywhere in this piece; compositionally, certainly, but particularly also in Linda Merrick’s simply gorgeous sound and phrasing, and her complete comprehension of what Manduell wanted. The final Manduell piece is a playful work for recorder and piano, Tom s Twinkle, brief and to the point, described by the composer as a “short jeu d’esprit.” It was written in memory of the composer Thomas Pitfield (lecturer at what was then the Royal Manchester School of Music). Choosing 11/8 for Tom’s Twinkle was in itself a homage to Pitfield’s penchant for such irregular time signatures.

Far grittier is Michael Berkeley’s A Dark Waltz for recorder and string quartet, dedicated to Manduell’s memory. It is in essence a “Valse triste,” originally for recorder and string quartet (as it is heard here); there is another version are for oboe and string quartet. It is intriguing how the waltz morphs into a shadowy processional; it’s a mini-masterpiece. Turner’s solos are compelling, as is the interaction of recorder with string quartet. Superb chamber music playing is on offer here from Turner and the Victoria String Quartet.

It is William Blake who provides the texts for five of Alwyn’s songs from “Songs of Innocence.” It was written in 1931, and the writing is charming and deft; we hear five of the 12 songs in a realization by David Matthews, himself a noted composer. Alwyn taught Manduell composition for two years at the Royal Academy. In the fresh tenderness of these songs one can see why Manduell admired Alwyn so much. Speirs again excels, while the ear is often drawn to the gossamer textures of the Victoria String Quartet; Phil Hardman’s recording (produced by Paul Hindmarsh) allows all detail to flower. The final song, “Nurse’s Song,” is particularly effective, an invitation for children to come in from play as the sun is setting (and their reluctance to do so).

Another Renaissance Man, Richard Stoker (1938-2021), another Lennox Berkeley pupil and friend of Manduell, offers Memento Mary Magdalene, a piece for recorder and string quartet that is an offshoot from his activities as an actor in the filming of The Da Vinci Code (2005). This is a lament for Mary Magdalene, and it is marked religioso. It is incredibly powerful, and certainly acts as an invitation to investigate more of Stoker’s music. There are only two reviews of Stoker’s music on the Fanfare Archive, and at least one of them is problematic as the disc is now so old it might be hard to find. Reviewed in Fanfare 2:3 (Jan/Feb 1979), Stoker’s three string quartets and a Miniature String Trio were played by the Strange Quartet, music which reviewer Lewis Foreman found “Bergian” (not something I hear in the Memento, particularly); Stoker’s op. 5 Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano was played by Einar Johansson and Philip Jenkins on a mixed clarinet and piano disc on Chandos (Fanfare 16:3, a piece rather dismissed by John Bauman as “hardly great music”). There is much variety on this disc, and much to be treasured. Extensive notes seal the deal.

Recommended.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978