Atlanta Audio Club

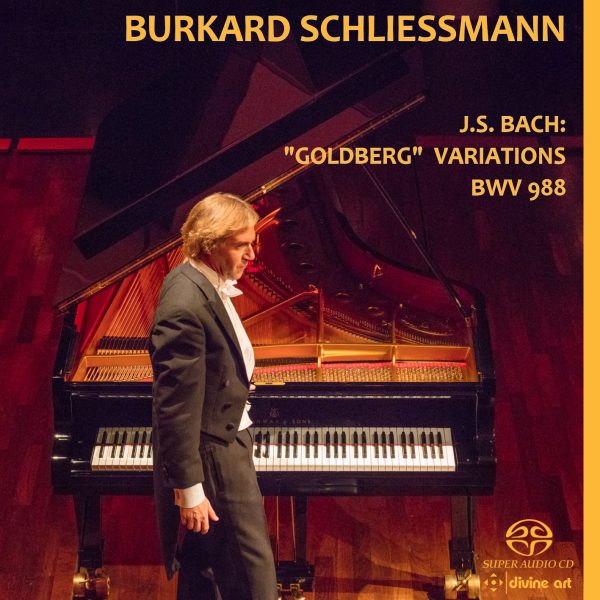

If we didn’t know better, we might have imagined that Johann Sebastian Bach wrote his great Goldberg Variations with the foreknowledge that it would be performed several centuries later on by an artist with the temperament and patience of Burkard Schliessmann. Certainly, our German contemporary comes well equipped for the task, being a dedicated musical scholar as well as possessing the mature keyboard technique needed for the Goldbergs. As I remarked of this artist some time ago, he is the last sort of pianist you would expect to just play the notes as written, and without comment. That is important because Bach’s approach to the Variations, while exhaustive, was not perfectly intuitive.

Nor was it intended to be. As he did in his Well-Tempered Klavier, Bach was working from a theory of harmony that was well in advance of the music of his day, with clear guideposts as to what the future held in store. The Goldbergs consist of thirty variations on an Aria da capo that is essentially a slow Sarabande. It is an emotionally moving, highly ornamented melody in three-quarter time with a descending arpeggio midway through that always gives me goose bumps, as often as I’ve heard it. These variations are also unusual in that they are built on the bass line of the aria, rather than its melody, a procedure that yields high dividends harmonically.

The variations themselves occur in groups of three, with the third being an imposing canon in which the melody in one hand is imitated by the other in a succession of ever-increasing intervals, from a canon at the unison (Var. 3) to a canon at the ninth (Var. 27). Of particular interest is the way the variations in the second position in each group of three (Nos. 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, 23, 26, and 29) may be taken to constitute what Baroque scholar Ralph Kirkpatrick described as “arabesques.” Performing them requires feats of prestidigitation, involving much hand-crossing and considerable freedom and flexibility of arms, hands, and fingers.

Starting off with a stately French Ouverture in dotted rhythms, there is a lot of musical treasure to be absorbed in the Goldberg Variations in terms of harmonic theory, technical challenges for the performer and sheer auditory pleasure for the listener. The latter may rightly sense there is a compelling drama unfolding here, without knowing exactly how or why. We leave that to a skilled interpretive artist of the calibre of Burkard Schliessmann. Suffice it to say these variations never fail to intrigue, in many ways. For many, the emotional deep point of the Goldbergs will be Variation 25, which famed harpsichordist Wanda Landowska described as the “black pearl” of the set. Its message of solace and consolation for a weary world is as much in need as ever in our time. Another is the repeat of the Aria da capo at the very end, a moment that always bring a lump to my throat. As Schliessmann rightly surmises, the notes are the same as we heard at the beginning, but there’s a difference. They are sadder, softer, wiser. We feel we have been on a long journey.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![Listen to the full suite of Marcel Dupré’s Variations Sur un Noël, Op. 20 from Alexander Ffinch’s #Expectations release today! listn.fm/expectations [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/588904367_2327488161082898_8709236950834211856_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=105&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=BGoHgV_YYfIQ7kNvwHw-krK&_nc_oc=AdnhCz2XLzNs_0K5c-205in3YNZ_Eng2zrdmv-D0d6UfUlspJmpoCM_4EkDmYSAG6xb-vWOtLJ1TxGy-TWhzRcU-&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=cTnzb89e29YnamiWSL5fwQ&oh=00_AfoGCpXGkFxDaWz4-kQxY0eimJ3AdTl5LdyccyvGME9S8A&oe=695E6B6A)