Fanfare

This performance was recorded in 2007 (there was an interview and review around it in Fanfare 31:3); this is the 2022 remastering, available also on Dolby Atmos. I have followed Atmos since launch, and feel it is a force for good; and if anyone needs convincing, this release will do the trick. The sound here is anything but “floaty” (a frequent criticism of Atmos); it just feels perfectly positioned. We hear everything as Schliessmann intends; this review auditioned both via Atmos and the physical Super Audio Compact Discs, and it is Atmos that feels the most involving. The sound feels purer, more crystalline; if tehre is a visual analogy, it is like one’s first upgrade to Bluray from DVD. The aim of all of this – recording ,transmission medium, player, piano – is to make us forget they are there and to bring us to Bach via Schliessmann, Divine Art and Dolby Atmos conspire to come closer to this ideal than anyone else. On a purely musico-emotional level, I derived more pleasure from the Apple Music Atmos medium.

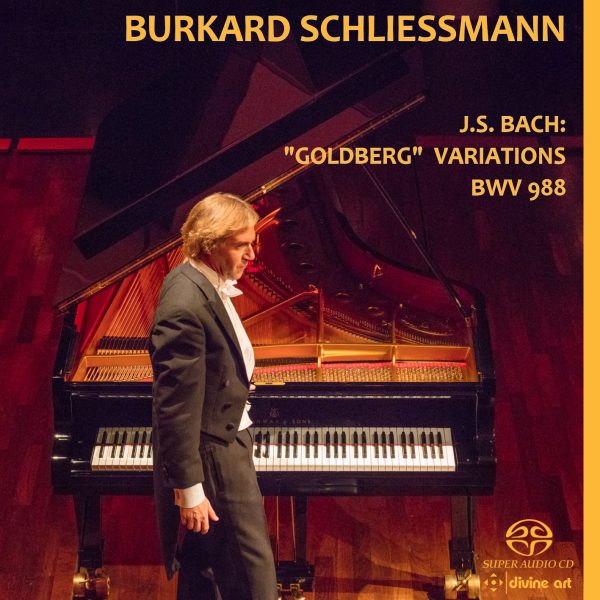

Schiessmann’s decision to play Bach on the piano might lose some purist listeners, but it would be their loss. The intellect that has gone into this realization is huge; similarly, the emotional range. As one listens, it feels as if the wisdom of centuries is somehow filtered down via some sort of alchemical distillation into the theme. Schliessmann gives the theme pace (one can hear the shadow of a slow dance in the background). The Aria also demonstrates the superior quality of his own Hamburg Steinway (the recording was made in Teldex Studio, Berlin). That “his own Hamburg Steinway” is significant, as Schliessmann knows this instrument inside and out; it is an extension of himself. Listen to the glistening clarity of “Variatio I,” and his way with the ornaments, free and improvisatory, and yet the pulse remains ever intact.

It is the freshness of the play of voices that impresses so much; dialogues proliferate (listen to the ever-so-civilized one in Variatio 3). This approach also enables a real sense of humor (Variation 23). Schliessmann’s touch is impeccable; so much reminiscent of that used by Argerich in her classic DG recordings. Yet his rapport with Bach is if anything closer. By bringing a sense of play to this performance (and with it, light), Schliessmann almost invites us to reframe Bach’s intricacies as expressions of joy. This is the pair opposite of the lumbering high seriousness of Lang Lang’s disaster of a traversal (DG). Tempos, even when he reinvents a variation (as in the Tempo di Giga, Variatio 7), feel perfectly judged. There is no hunt of awkwardness that even the best can bring (I think particularly of Variatio 8) where even Angela Hewitt (either Hyperion version, or even in a live performance I attended in Manchester, UK) can sound just a touch off-track; the same could be said of Schliessmann’s cat-and-mouse way with Variation14.

The sheer variety of touch on display is remarkable. Variatio 13 seems to demonstrate this aspect of Schliessmann’s performance in microcosm. At the heart of all of this seems to be an awareness of Affektenlehre; listen to how the sighs of the Variatio 15, of the grand gestures of the Ouverture that opens the second part (Variatio 16). The remarkable Variatio 25 (sometimes called the “Black Pearl” variation) becomes the emotive heart of Schliessmann’s account; just shy of ten minutes’ duration, he makes sure we hear the sheer modernity of Bach’s writing. Interestingly, the decorations of Variatio 26 feel modern after that, ahead of their time (as Bach was, of course), as does Variatio 28 (with its neighbor-note oscillations that explode into joyful lines). Yet the nobility of Variatio 30 is absolutely of its time.

The return to the beginning, the Aria, at the end has the effect of closing this cycle of a Universe co-created by Bach and Schliessmann. This is important, as it means that what we experience in this traversal is exactly what variation form brings: the examination of an object (the “Aria”) from a multiplicity of viewpoints.

The booklet note is extensive, a university-grade lecture, and cherishable in its own right. Schliessmann’s recorded Bach is human, alive. It rejoices in its own endless ability to create from a germinal cell (the “Aria); its exuberance is never-ending.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978