Infodad

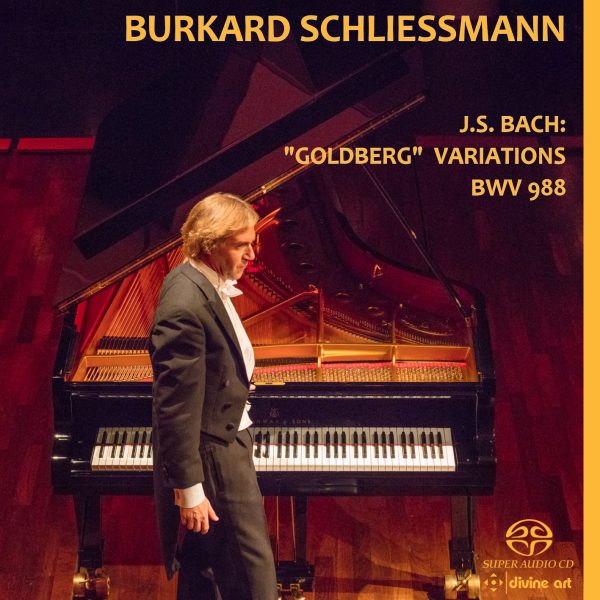

Burkard Schliessmann is very thoughtful in his performance of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, but his recording, originally dating to 2007, is a highly polarizing experience, and the very fine re-release on the Divine Art label only confirms the difficulty of knowing just how to react to it. This work remains a litmus test, or perhaps a Rorschach test, for keyboard players – and often for listeners as well. The issue with Schliessmann’s interpretation is not just a matter of his use of a piano – a historically inappropriate decision, to be sure, but one made by many performers and sure to continue being made by plenty more – nor even his willingness to employ the very Romantic and post-Romantic piano sound and capabilities to emphasize various elements of the music. In fact, Schliessmann actually does use period practices here and there, as in runs of short-value notes; but when he does so, the attentiveness seems grafted onto a very different sort of performance and does not come across as a genuine attempt to be somewhat historically informed. For example, one reason Schliessmann may adopt that particular short-note-value element – in Bach’s time, notes in such runs were played somewhat unevenly – is that the performance as a whole has a rhythmic freedom, a willingness to stretch and compress elements in the service of emotional communication, that goes well beyond what is usually incorporated into the Goldberg Variations.

To give Schliessmann his due, it seems that he wants, above all, to make contemporary listeners comfortable with Bach’s music, to have them hear this piece not as a museum piece and not as a doorway to an earlier time, but as a work with as much to say in the 21st century as in Bach’s own time. The difficulty, though, is that Schliessmann’s is scarcely the only way to make this sort of connection with modern listeners. The rhythmic freedom that Schliessmann adopts deliberately is so pervasive that it seems, after a while, to become a mannerism. Tempo changes are another issue: Schliessmann does not really employ rubato, which would involve speeding up an element and then slowing down another to compensate – instead, his tempo choices often seem rather arbitrary, interfering with the sense of flow and forward motion of the music in an attempt to make it more expressive and involving. Also, there is an unevenness to Schliessmann’s handling of ornamentation, so that it seems crucial in some variations and an afterthought elsewhere. What the performance lacks, then, is consistency. This is clearly music about which Schliessmann has thought carefully, and which he wants to present in a way that today’s audiences will find congenial, meaningful, and salutary. To Schliessmann, that turns out to mean handling it sometimes with neo-Romantic (or proto-Romantic) flair, sometimes with a kind of diffidence that downplays the elegance of the work’s construction. Certainly this recording shines some new and different light on a very-well-known piece, a cornerstone of the keyboard repertoire. And listeners looking for something unexpected from the Goldberg Variations should find at least occasional elements of Schliessmann’s performance intriguing. But taken as a whole, it is hard to take as a whole: it is a collection of individual elements that often engage, sometimes misfire, but rarely connect effectively as parts of a total experience.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![Listen to the full suite of Marcel Dupré’s Variations Sur un Noël, Op. 20 from Alexander Ffinch’s #Expectations release today! listn.fm/expectations [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/588904367_2327488161082898_8709236950834211856_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=105&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=H3rHeRayPTgQ7kNvwE0abDP&_nc_oc=Adk9NjnEalCvgLhD9JBsuBgybfcmXQSfSP3-YTsPBnraDl5DY7-F_Vgjy91SXqRRYYGJhZ6gmlvoA_vn9l5XWqSG&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=43IJWCNwCEmAc64y2q97Cw&oh=00_Afm4j7dl0hN9lQ8WVHPt4AoZ35nWsRTJ29LJ_aHY84uP0A&oe=6958B4EA)