Fanfare

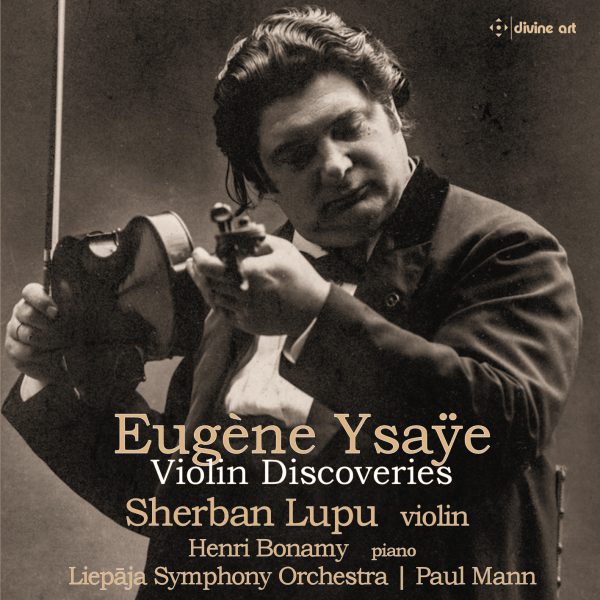

Sherban Lupu presents a gift of a disc here. It is amazing to hear the stories in the interview above that led to the resurfacing of this music. Every single piece is of great caliber, and Lupu gives each piece its all. His advocacy is never once in doubt. For the pieces with piano, he is more than ably partnered by pianist Henri Bonamy. The first of the Scènes sentimentales featured here is No. 3. This music is charming, yes, but it has a core of strength behind it that gives it substance. The music dates from the time of the composer’s decision to leave Berlin and return to Paris to make a life as a concert violinist. There does indeed seem to be a sense of freedom here, and Lupu communicates this viscerally in the way he throws himself into the technical challenges. The second piece chosen from the Scènes sentimentales is No. 5, very much its companion’s sibling emotionally but perhaps with a more extroverted edge. It is worth turning the ears towards Henri Bonamy’s playing here, for although there is no doubt that the violin is the featured instrument, the music itself is inspired. Ysaÿe’s melodies are to die for, and he seems possessed of an infinite fountain of them.

The Elégie is rather later; the Scènes date from 1885, the Elégie from around 1912. The Elégie is darker, more veiled, and Lupu responds with a deliciously conspiratorial tone, as if whispering a secret into one’s ears; the harmonies, too, are more sophisticated. The three Etudes-Poèmes, a wonderful hybrid title, date from 1924 and comprise “Serenade,” “Au ruisseau,” and “Cara memoria.” They were intended for publication as a set in 1924, but that never came to fruition. It is the world’s loss, and it is our gain that they are here now. The “Serenade” is a glorious outpouring (and not without wit in Lupu and Bonamy’s performance), while the central “Au ruisseau,” with its emphasis on double-stoppings, bonds technique with expression in what must surely be a finger-twisting way. Lupu finds great suavite here as well as lyricism, with Bonamy perfectly judged in the background (the positioning in the recording of both of them is fabulous). Finally, “Cara memoria” is as sweet as the title suggests. This final piece is by some way the longest, at over 11 minutes (the other two are 3 or 4), which gives the music space to stretch. It is cast as a funeral march, its relentless tread nevertheless relatively unthreatening. Its effect is cumulative, and as the piece progresses the harmonies seem to twist and turn.

The short Petite Fantaisie romantique pretty much does what it says on the tin, but with awe-inspiring expertise. Lupu’s violin positively sings here with a most appealing insouciance (it is also the only piece here that is not receiving a world premiere recording). But the real work of archaeology here is the G-Minor Violin Concerto of 1910, heard in Sabin Pautza’s 2017 orchestration, clearly a labor of love. Cast in one 25-minute span, the work is patently inspired, and there is a complementary sense of discovery with the musicians of the Liepaja Symphony. The work sums up the achievements of the composer’s middle period The violin entrance is remarkable, with what sounds initially like a full-blown cadenza right at the opening; more than this, the violin takes the music to more extreme grounds than the orchestra has so far dared to traverse. The booklet notes for the release describe this solo section as a “prayer”; it certainly stands in contrast to the outdoorsy freshness of the subsequent orchestral passage. There is no doubt that conductor Paul Mann fully understands the structure of the work, and his grasp of individual outbursts’ trajectory is sure and fast.

The technical demands of the concerto are huge, and Lupu is remarkable here—nay, inspired, be it in the more assertive passages or in the searching demeanor of the development (from 8:13). It is true that one can hear the influence of Debussy at times, but the overall impression is of a strong individual compositional voice. The violin’s songful ruminations are perfectly integrated with the orchestra’s tapestry, and the Divine Art recording allows maximal detail through.

The whole experience of the G-Minor Concerto is not just that of experiencing the new; it is experiencing a new piece that is artfully, masterly constructed and which contains real passages of genius. The way the composer is able to reconcile moments of real dissonance with others of sheer melodic expansion is remarkable. The orchestration, too, is a work of art in itself, in particular in the deft handling of the woodwind instruments, and also allows for moments of real sonic revelation: listen around the 10-minute mark to glowing harmonies and scoring that Zemlinsky would not have been ashamed of. And yet there is no contradiction in the inclusion of a slinky dance around the 17-minute mark. (Notice how Ysaÿe can slip a tonally based phrase easily into more progressive territories, and out again; it really is masterly.) Brass are used sparingly but at moments of power, while orchestral strings carry Romantic melodies of great sweep (clearly relished by the musicians in this recording). The concerto is a gift to music from the world of musicological academia. Brought to life by performers who show the utmost commitment, this is an unmissable disc that introduces a work of real substance. Without doubt, a most important recording. Now I just want to hear the piece in a live performance.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![Listen to the full suite of Marcel Dupré’s Variations Sur un Noël, Op. 20 from Alexander Ffinch’s #Expectations release today! listn.fm/expectations [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/588904367_2327488161082898_8709236950834211856_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=105&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=H3rHeRayPTgQ7kNvwEiwjui&_nc_oc=Admo0BYH7-mr61Q0mTg3R7v48XmVpapZXymfWpJy5TgkHUNcBovXYn_S73k1NOip06M&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=LX30xhuyTLZLtiThTj9l8w&oh=00_AfmhAwkV2LXweXY7aqjrrkoMdLsVQME2LXQAPcTezBy8Aw&oe=695A76EA)