Fanfare

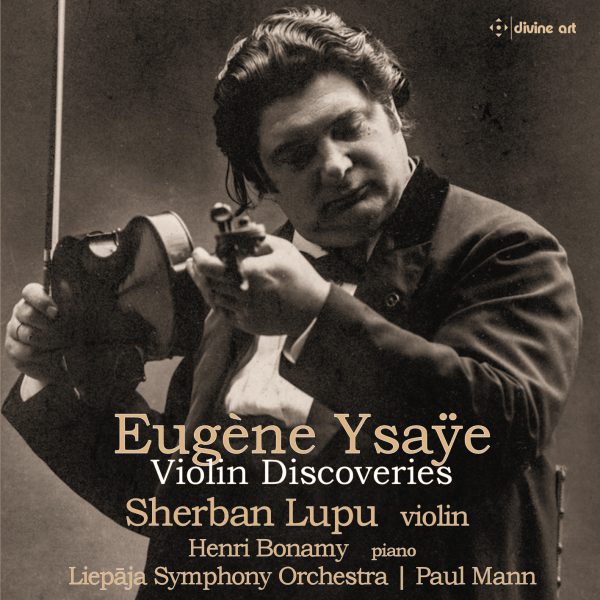

I’ve felt the pull of Ysaÿe ever since I first heard one of Oistrakh’s recordings of the Third Sonata—and that pull has only grown stronger over the years, even though (or perhaps because) the music is so elusive. It’s elusive along numerous axes. Stylistically, it resists classification, especially in the works from his mature years; emotionally, it is more likely to play with ambiguity than to engage in clear expression; formally, the music is apt to move in unexpected directions, although it’s more searching than meandering. Then, too, performances are elusive. While the Sonatas for Solo Violin have moved into the standard repertoire, you don’t often run into the rest of his output. Finally, the music is elusive because so much of it has been lost or—as this CD (Eugene Ysaÿe:Violin Discoveries) demonstrates—hidden away. Other than the Petite fantaisie romantique, which was recorded in 2018 by Philippe Graffin and Claire Desert, all of these works are disc premieres. Specifically, they are all the result of intense archeological research by violinist Sherban Lupu, who searched for them, discovered them, and went on to create performable editions (with a significant contribution from Sabin Pautza, who did the bulk of the orchestration for the concerto and who ingeniously fabricated a replacement for the missing piano part for the first of the Etudes-Poèmes). It would be hard to overstate the importance of this release.

The importance—and the aesthetic pleasure. Most striking is the concerto. Ysaÿe left a number of early concertos in various states of completion (see, for instance, Fanfare 32:5 and 43:6)—but this newly restored G-Minor work, from 1910, is something else again. Begun as early as 1893, it has a complicated genesis (well explained in Qianyi Fan’s first-rate notes), but in this final form, it’s a massive 25-minute movement exhibiting an expressive breadth I’ve not heard elsewhere in Ysaÿe’s output. Its presciently Herrmannesque opening leads, strikingly, to a passage for unaccompanied soloist. That early cadenza is followed by a complex movement where Elgarian surges (it’s easy to hear why he was so sympathetic to the Elgar Violin Concerto) are interwoven with passages reminiscent of Debussy at his darkest (the gloomier moments of Pelleas, for instance), a movement where patches of bittersweet Tchaikovskian lyricism dissolve into shocking violence, a movement that eventually builds to a grand ending that (surprisingly) sounds like a shout-out to Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony. Then, too, while it’s harmonically more conventional than some of Ysaÿe’s later pieces, it still throws you off balance in troubling ways. Yet despite this stylistic disparity, despite the harmonic slippages, the music never sounds like a hodge-podge. You may never be able to guess what’s coming, but whatever does happen seems, in retrospect, well motivated. Without access to the manuscripts, it’s hard to tell just how much editorial intervention there has been—but as it stands, it’s a work well worth knowing, even if your interest in Ysaÿe has not gotten much beyond the sonatas.

If the concerto had appeared by itself on a CD, I probably wouldn’t even have complained about short measure. But there are plenty of treasures in the shorter works here, too: in the late Romantic combination of honey and fireworks in the first of the Scenes, in the deliciously unstable harmonies of the Elégie, in the off-kilter “Serenade” that opens the Etudes-Poèmes, and especially in the long and wrenching journey through grief to resignation in the Cara memoria funeral march that closes it. Sherban Lupu has gotten rave reviews on these pages, especially for his series devoted to reviving the music of Heinrich Ernst; and the same technical skill, interpretive sensitivity, and exploratory commitment are on display here, with knowing support from Henri Bonamy. Paul Mann, a conductor who also has a fine record of adventurous repertoire, gets solid playing from the Liepaja Symphony; and Divine Art’s engineering leaves no grounds for complaint. All in all, a significant release.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![Listen to the full suite of Marcel Dupré’s Variations Sur un Noël, Op. 20 from Alexander Ffinch’s #Expectations release today! listn.fm/expectations [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/588904367_2327488161082898_8709236950834211856_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=105&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=BGoHgV_YYfIQ7kNvwFumfck&_nc_oc=AdlG2NmBCXgRk3X1IpNBYg5IlHNxNiLDActv144eM5pRncnCx0GPpZ88gGTMZzhpwLQ&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=2OKFG2ndb0-TFDivc4ipeg&oh=00_AfqYA2t0mD75dMjAsHZPl-qcGlIYKQmSpXBaJb5OBhvaCw&oe=695E6B6A)