Fanfare

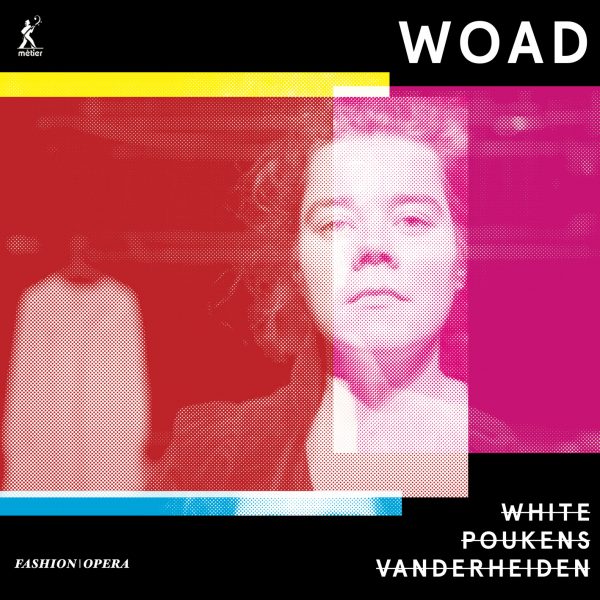

This is really quite remarkable: a “fashion opera” (the composer’s own term) that retells the story of the Scottish legend of Tam Lin, but with an immense range of reference. It is scored for only soprano and saxophone; the composer himself is librettist. White’s concentration of musical language is highly impressive, used throughout towards the highest expressive goals.

Scottish composer Alistair White was born in 1988. His music is uncompromisingly atonal. But it is also intensely lyrical at heart, and there is no contradiction whatsoever between the two. (Think of the best performances of Webern songs you ever heard, how they find beautiful phrasing and sense of line in the disjunct intervals.) The story here is that of Tam Lin, a traditional Scottish tale of transformation: Tam Lin was captured by the Queen of the Fairies, and White’s music invokes a liminal space, transitional between worlds and therefore capable of encompassing a multiplicity of expressive means. The story may be archaic, but the text references certainly are not: the libretto begins (after the singer states the scene, as she does subsequently with each scene), with the line, “Death Metal’s not the same as Thrash.”

There is humor in the libretto: in the fourth scene, “Tam’s Speech,” the narrator, Tam, says, “Of course I google myself from time to time, who doesn’t?” The ability to reference contemporary phenomena within an ancient frame seems at the heart of this piece, just as White brings in a flexibility that enables him to explore the concept of versions of events co-existing “in different areas and types of spaces.” There’s a sense of Birtwistle and his myths here, particularly in the parallel, simultaneous tellings of two versions of the same myth in The Mask of Orpheus. But for Birtwistle that remains an aspect of the nature of myth itself, while for White it seems more a reflection of the multiverse theory in which multiple paths do in fact take place, but in different “dimensions,” and that presumably extends to physical events as well as mythological ones. That lyricism mentioned previously seems particularly present in that fourth scene, be it in long lines or, perhaps more obviously, a sense of the dance. The fifth scene, “Interim: The Painted Ones,” seems at once a “slow movement” and a still center around which the rest of the work orbits.

Words cannot really express my admiration for Kelly Poukens and Suzy Vanderheiden, whose talents seem funneled towards White’s score until they merge as one in his service. Poukens’s range is huge, and her pitching spectacularly accurate. It is one thing for a saxophone to move rapidly from a low note to a high one, quite another for a soprano to do so. Both singer and saxophonist have complete control over their modes of delivery, as we hear in the work’s slower sections. Try the sixth scene, “The light that,” not just in the expressivity of the lines but also in the purity of tuning of the dissonances; it is almost prayer-like at times in its intensity.

It is worth following the libretto for the final scene in the booklet as one listens, as the spatial layout of the text is markedly deliberate. This includes an extended solo sax “song,” plaintively, touchingly given by Vanderheiden. Here, White comes as close as he can to stating the liminal heart of his piece, as he talks of the “space between before and after,” and names several other examples of liminality before setting text that moves across white gaps in the space of the printed page, where just as our eyes traverse the page’s whiteness, the performer’s phrases traverse silence, only to be taken up again. Another Webernian parallel, perhaps, that silence becomes such an integral part not just of the musical experience but of the musical phraseology itself. The opera WOAD is preceded by the operas WEAR and ROBE but also exists as a self-sufficient entity. Another White opera, RUNE, gained much critical praise in August 2021, when it was performed at the Round Chapel, Hackney (London, UK). White seems to have created not just his own voice within opera, but his own type of opera as well. It is a magnificent achievement to do so, and its manifestation here in WOAD is the height of compositional magnificence, performed by two musicians at the very peak of their powers. The recording is everything one could wish for: vivid, present, detailed. Unhesitatingly recommended to the brave, and a prize candidate for my next Want List.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978