Infodad

The rediscovery of fine, unfairly neglected works of past times is an ongoing pleasure in classical music today, with more and more artists performing works that go beyond the mainstream ones for which composers are known – and with new findings occurring with considerable regularity. To be sure, much re-found music and many re-found composers turn out to be justifiably obscure; but it is nevertheless remarkable how many really fine pieces of music have slipped through the cracks of history, providing opportunities for today’s performers to explore unfamiliar repertoire that certainly deserves a better fate than it has had to date.

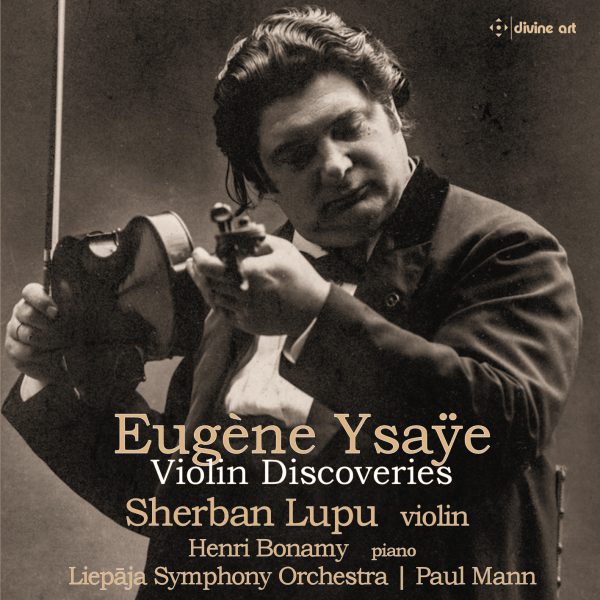

A new Divine Art CD featuring Sherban Lupu playing music by Eugène Ysaÿe is a fine example of works whose near-total obscurity is difficult to understand. Only the brief, charming and unprepossessing Petite fantaisie romantique of 1901 has been recorded before – everything else here is a world première recording, and the G minor Violin Concerto of 1910 was wholly unknown until Lupu helped reconstruct it and Sabin Pautza orchestrated it as recently as 2017. The concerto, in a single very extended movement, is the major work on this disc, and it is a real find. Unexpectedly, given Ysaÿe’s virtuoso reputation, the concerto begins with a two in-depth minutes of orchestral exposition before the violin even enters. And when the soloist does appear, it quickly becomes apparent that this is not a virtuoso vehicle but a complex, forward-looking-for-its-time study in interactivity between solo and ensemble. Since Ysaÿe did not orchestrate the work, it is impossible to know to what extent the actual sound of the concerto is what the composer intended – but the harmonic elements and instrumental interplay, which often sound like a mixture of Richard Strauss and Ravel, show that Ysaÿe was looking well beyond the Romantic era while clearly incorporating the musical richness and emotional intensity of that time period. Lupu plays the concerto with real panache, and Paul Mann provides sure-handed support – just as pianist Henri Bonamy does for the remainder of the pieces heard here.

The Scènes Sentimentales date to 1885, when Ysaÿe was 27, and were designed as showcases for the composer’s performance techniques. They are effective in that respect, if not musically very memorable. The first two of the Trois Études-Poèmes (1924), the latest music here, are also primarily technical showpieces, but the third and by far the longest, called Cara memoria, is a fully developed work with elements of tone poem and sonata movement – written with less of a “modern” harmonic approach than the first two pieces, but far more effectively constructed. And the Élégie of 1912, which is the same length as the Petite fantaisie romantique, is less of a salon piece than the earlier work and more of a study in Impressionism, albeit only in a general sense. This CD is a remarkably engaging exploration of some byways of the violin’s past, and it points quite clearly to the many fine works that Ysaÿe wrote for his instrument beyond the six famous solo violin sonatas of the 1920s.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=49FisD1EbHcQ7kNvwG1eC7D&_nc_oc=AdmQyODh0fak0FLW23v-OG3eixfQjvyp2rlRTzdxhyku1ZB7Mgjz05SX42iDPF0G_jyub7jWPEanq68P6FQSWgUS&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=qIgiBzsaINTCckkyntRR6A&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQGoJ0V4pMxfFXOG_isVS4Ax1OqUFT60xUzlB_mIdoQ3RvTurraLa2oVAm0rJCP4fCzhv6ju58M6dA&oh=00_Afybst5xhCyJ2n3tdt2x3GJRVZrF6aauqLSsghoztUb9nA&oe=69B56C01)