Fanfare

The intrepid violinist Peter Sheppard Skaerved has devoted his life to furthering the repertoireof his instrument; in this case, works by the Icelandic composer Haflidi Hallgrimsson. Bom in 1941 in Acureyri, the northernmost reaches of Iceland (at the foot of the Eyjafjordur Fjord), Hallgrimsson enjoyed a European education, studying the cello in Rome; later on he went to London, to the Royal Academy of Music to study composition with Alan Bush and Peter Maxwell Davies. For many years after, he was principal cello with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. It was not until 1983 that he left the orchestra, turning full-time to composition.

Hallgrimsson wrote a few short pieces for Sheppard Skaerved in 2005 for a recital the violinist was giving in an art gallery in Mexico City. The composer returned to these slight pieces much later, adding more until his op. 32 (2005-19) consisted of two “books,” which gives the performer the option to extricate individual pieces or small groups of pieces for recitals as required. The music requires a highly skilled performer, and from this perspective it is difficult to imagine anyone more suited than the present violinist.

The slower movements carry real pathos: “Klee experimenting with a new scale” might sound a dry exercise, but the reality is anything but. Klee is of course famous for “taking a line for a walk” and that’s the title of the fourth movement, properly exploratory. While some of the realizations begin with the obvious route (“Don’t neglect your pizzicato Herr Klee,” indeed all pizzicato), the result itself is never predictable. There is a restraint here that implies a composer who enjoys beauty. There is something, too, about a field of mainly low dynamics that draws the listener in, invites us to share the subtleties.

The second book of Klee Sketches is just as remarkable as the first. I find the pizzicato in the first number, “Klee the artist plays his violin,” absolutely hypnotizing, like tiny bells marking time in a (sometimes surreal) arco world. The lachrymose music immediately suggests a link to the mourning of Offerto in “Klee performing at the grave of his father.” How light in contrast is the very next movement, “Klee observing a large butterfly.” As for Hallgrimsson’s take on birdsong in the final movement, “Klee notates birdsong in the aviary,” it is about as far from Messiaen as one can get, utterly individual while identifiably avian in inspiration.

Sandwiched in between the two books of Klee Sketches is Offerto, op. 13, “In Memoriam Karl Kvaran.” This is another piece linked to painting, then. Karl Kavaran was an Icelandic abstract painter who died in 1989; he was also a friend of Hallgrimsson, and there is indeed a tenderness that shines through. The work’s trajectory begins in the numbness of early grief (Hallgrimsson refers to it opening quietly, “like a trembling hand writing an obituary”). The increased activity of the second movement, “Lines without words” (which itself could refer to the surrounding Klee), describes the artist at work alone in his studio. The active and more forceful “The flight of time” is, again in the composer’s words, “like a flight of a meteorite”; Sheppard Skaerved is magisterial in his command of his instrument. We are reminded in this movement that this is the violinist who recorded Paul Pellay’s Thesaurus of Violinistic Fiendishness (reviewed by Robert Maxham in Fanfare 36:2) before the gentle, solemn unfolding of lines in “Almost a hymn,” wherein Sheppard Skaerved’s control at the lower (almost inaudible at times) dynamics is absolutely impeccable.

Documentation is detailed, as is only right for new works. Amazingly, the disc was recorded on only two days (nearly two months apart). The recorded sound from St. Michael’s Highgate (London) is perfectly judged, thanks to Jonathan Haskell; Sheppard Skaerved doubled as performer-producer. As time was probably tight, it is probably highly inappropriate, not to mention greedy, to suggest it would be nice to hear the different versions of the pieces which are identified as either “Version A” or “Version “B” in the listings. (For “Frau Klee is sleeping” from Book 1, we get version B and are told that that is actually the second of three versions; and “each time it has become more beautiful,” according to Sheppard Skaerved.)

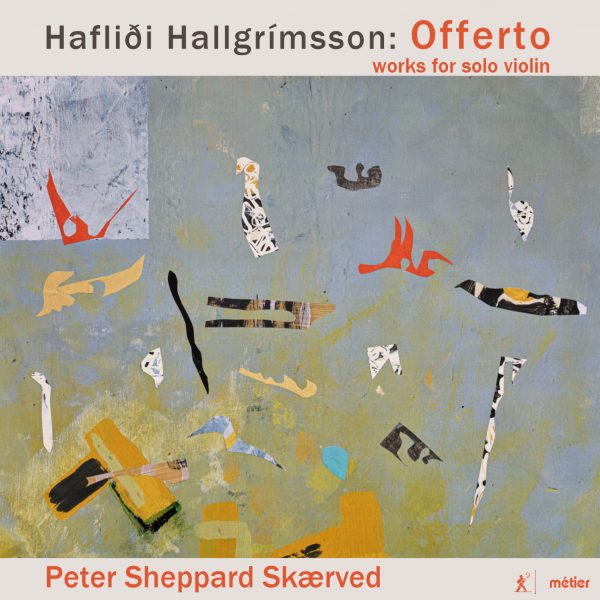

Perhaps the finest praise I can give is that I am not a violinist, yet I found this transfixing throughout. I would love to hear more Hallgrimsson. And, as a final cherry on top of this violinistic cake, the beautiful cover art is by Hallgrimsson himself.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=iGIrDXgtiUoQ7kNvwHg1pC_&_nc_oc=Adng67nnlZzfgGN4JYYkRiqLorW1S62X4s25qQK-2KDJZ1M5YJGS-M_sDfXvBWZ6F6juoUGvquL06fnHt4GDsgdV&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=sWTtk3XKlWQKI0yBrJgLdQ&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQGIDvMR9oXyK9kGYU6zt-awQcGgk3PMk2fQ1jsrBKrhhCMlZr-NIgk_u4Fp0am0WFwV4yGq0dFqHQ&oh=00_Afx6_iHh5fzIEtOJ0ujii1WbUSls0lY9O-Wk_GFEld7tag&oe=69B452C1)