Fanfare

Four concertos by Marius Constant, recorded back in 1990, show him as highly eclectic. His modernist, tonally sophisticated language incorporates diverse influences including modern jazz, classical structures and ethnic music. To give you an idea of the breadth of his musical interests, the three movements of his Saxophone Concerto are titled Raga, Tempo di cakewalk and Passacaglia. One of his concertos is for barrel organ; its second movement is a free fantasia on a theme by Beethoven. Until now, that Erato concerto disc seemed to be the last new recording fully devoted to Constant’s music. The only recent releases have been two performances of his idiomatic orchestration of Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit.

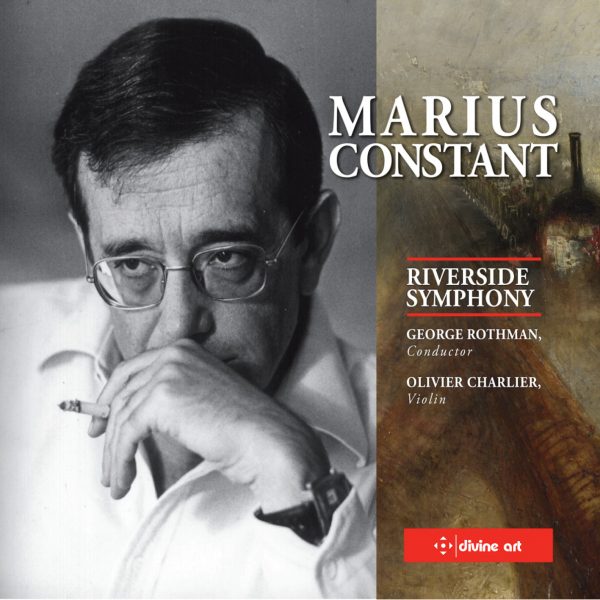

The composer was born in Bucharest in 1925 but spent his adult life in France where he wrote several ballet scores for Roland Petit, founded the Ars Nova Ensemble, conducted frequently, was director of dance music for the Paris Opera, and taught at the Paris Conservatoire. An individualistic composer, Constant’s career was hampered to some extent by the fact that he did not run with the Boulez crowd. The avant-garde criticized his eclecticism as superficial, to which Constant quoted the Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran: “No one achieves frivolity without a struggle.” His best-known piece of music is the theme to the 1950s sci-fi television program The Twilight Zone, which was actually assembled from musical fragments he submitted to CBS as all-purpose dramatic stings. He died in 2004; none of the obituaries mentions anything about his personal life.

The three works on this CD span thirty years. The earliest is Turner from 1961, a suite of three tone pictures after paintings by J. M. W. Turner (often cited as the “first Impressionist”). The paintings are Rain, Steam and Speed (the painter’s masterly depiction of a speeding train from 1844), the rather ambivalent Self Portrait and the somber hunting scene Windsor. Constant, who described himself as an “instinctive” composer, is revealed as an evocative orchestral colorist in these pieces.

From 1981 comes a substantial work for violin and orchestra: 103 Regards dans l’eau (103 Visions of Water). Although in 103 short movements (!), each inspired by a particular view of water, the work also falls into an obvious four-movement structure, albeit with the slow movements at the beginning and the end. It is, as you would imagine, very fluid, but the music grows organically and the piece does not come over as fragmentary. The violin part is virtuosic in true concerto style with many solo passages, and the orchestration subtle and colorful as in Turner. Harmonically it is tonally based but contains avant-garde devices such as clusters, and no clear tonal center: the composer most closely suggested is Constant’s friend Henri Dutilleux. I can’t say I quite have this concerto’s overall measure yet––this review was written, of necessity, in some haste––but several sections stand out as adroit post-Impressionist waterscapes.

Brevissima, from 1992, is nothing less than a symphony, with an opening adagio leading to a symphonic allegro, a scherzo movement, a largo, and a passacaglia finale “qui culmine près d’un soleil brúlant” (to quote the movement’s title). The reason it is called Brevissima is because all this, with the requisite symphonic development of a recurring four-note motto, takes place over the course of ten minutes. Constant’s contraction of symphonic form is deftly done––the three-minute first movement even contains a gentle coda––and again the orchestral sonorities are a highlight.

I might add that none of these works is remotely jazzy, nor do they sound like The Twilight Zone, and they are far from superficial or frivolous. Both Turner and 103 Regards dans l’eau have been recorded before, the latter with the composer conducting the Berlin SO on a Cybelia disc that is now close to impossible to find, and again in a version that uses a reduced orchestration of 12 instruments. I have not heard either of these. I requested the new disc because of my previous interest in the composer, little knowing it would be such a knockout. Conductor George Rothman and artistic director/resident composer Anthony Korf founded New York’s Riverside Symphony in 1981. They play these works stunningly, and you understand why when you see the video interview where Rothman and Korf speak about the music with reverence and enthusiasm. (The video also includes an illuminating archival interview with the aged Constant.) Violinist Olivier Charlier’s previous recordings include the Dutilleux Violin Concerto “LArbre des songes” (with Yan-Pascal Tortelier on Chandos) so Constant’s concerto suits him admirably, and he plays it with élan. The musical standards are matched by the sound quality, which is first rate, the balance revealing the many details that make this composer’s music so fascinating. Charlier’s violin is recorded quite closely but that is no problem; in fact, it is an asset. Want List material without a doubt.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978