Fanfare

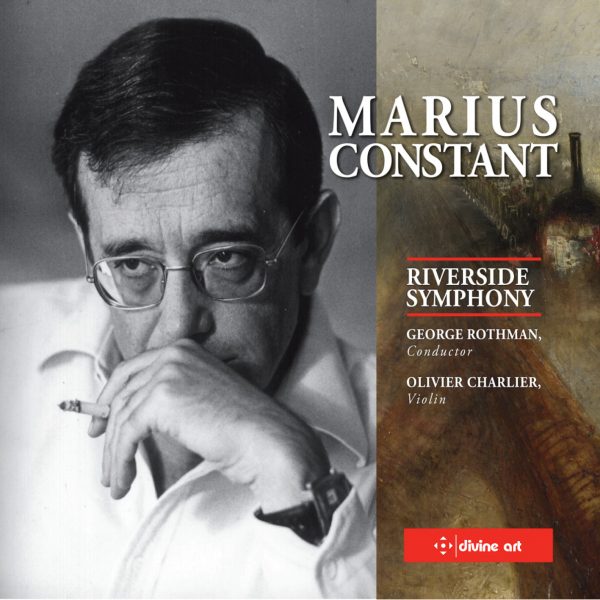

Marius Constant, when he wasn’t known for writing the Twilight Zone theme song, was mostly known as a ballet conductor for Roland Petit in Paris and the occasional composer of modern works, yet his own compositions never quite made it into the mainstream of the classical repertoire. A pupil of Olivier Messiaen, Tony Aubin, Arthur Honegger, and Nadia Boulanger, Constant had a restless mind, composing such works as Haut-voltage, Contrepointe, Cyrano de Bergerac and Éloge de la folie, and won wide recognition when Leonard Bernstein premiered his 24 Préludes pour orchestre in 1958. Two years earlier, in 1956, Constant jotted down s short (40-second) piece that he liked but had no immediate use for. Three years later, he submitted it in an international contest sponsored by CBS television to find a theme song for Serling’s proposed new show. It came to define him in America, which is a shame because his other music is powerful and fascinating.

Judging from the works on this disc, Constant’s style was one of sonic contrasts, one might almost say clashes, utilizing a sparse orchestral palette. Although his formal music, like the Twilight Zone theme, alternated quasi-tonal passages with jagged shards of melody, one would have to call him an essentially tonal composer who worked with modes and chromatics. He was not a 12-tone composer, which, the notes say, is partly the reason he did not receive international fame. I used to try following his career through the years, but in those decades before the Internet all you could really find out about him is that he was a first-rate conductor, particularly of ballet but also of opera and occasionally symphonic music. We heard that he was also a fine composer, but nothing much was recorded. The works on this disc, however, are really and truly outstanding.

Tonal yet abstract seemed the best description of his style. One feature that impresses the listener in all three of these works is that, for Constant, the initial inspiration for a work seldom dictated form or content. Unless one were told that the opening suite of three pieces were an homage to the great British painter J.M.W. Turner, for instance, it would be the last thing that would come to mind. Constant internalized aspects of the person or thing that inspired him and wrote to his own aesthetics. Although Brevissima was written 31 years later, its style and overall structure are very similar to Turner. In this work, however, I didn’t particularly like the very end, which just came to a crashing climax and then stopped, but most of the music is superb as is the playing of the Riverside Symphony.

By far, the most involved and involving work on the CD is the violin concerto, 103 Regards dans l’eau. Composed in 1981, it owes a bit in form and style to the violin concerto of Alban Berg, yet maintains much of Constant’s own personality, particularly in the orchestral accompaniment, which alternates between sparse (and sometimes non-existent) and powerful. My personal impression is that Constant was a composer who thought more in shapes than in colors. I “hear” spirals, trapezoids, and interlocking rectangles in his music, but in terms of timbre his basic colors are black and silver. There is light in his music but it is always a white light, either diffused or (more frequently) sharply etched against angular black shapes. The music builds and flows through the four movements which are marked in terms of tempo but nothing else. In the second movement (Agité, dotted quarter note=80), the fleet solo violin figures sound furtive and frightened, as if running for their lives until a percussion outburst slows the soloist down for the rest of its duration. Our soloist, Charlier, is a first-rate technician who fully enters the spirit of the music. Constant’s music—even the Twilight Zone theme—always sounds to me like the fabric of dreams. They are unsettling but not frightening dreams; one seems to be unable to find solid ground through most of it, but somehow you always come back down at the end. This violin concerto is no exception. After nearly a half hour of feeling weightless and unable to connect with anything tangible, the music ends on a tonic chord. It’s a soft, high tonic chord, but you still feel that there is closure.

The 15-minute video (which plays through Adobe, not Real Player or Windows) features conductor Rothman and artistic director Anthony Korf speaking about Constant and his music, interspersed with archival footage of the composer talking and conducting. A few brief moments are also shown of one of his greatest triumphs, the Cyrano ballet that he wrote for Roland Petit. Constant explains that the reason he stayed so long with Petit was that he wanted to get to know how to write for the theater, how to balance “action and rest, tension and release.” He also makes it clear that he was not an intellectual composer but instinctive, that he eschewed traditional classical forms to make up his own. We also learn that although one hears 103 Regards dans l’eau as a violin concerto, it is in fact made up of 103 separate shards of music. Korf speculates that it may be the only piece of music to do such a thing. Of course, none of this would mean anything if the music were not so gripping and moving, but it is, as are the performances of it. This is a desert-island disc.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978