The Art Music Lounge

Well, now, here’s another interesting composer and some very interesting music. Edward Cowie, a 77-year-old British composer barely known outside his native country, has been writing music since 1964. He is also a natural scientist, author and painter who views music as “a biological phenomenon and also a form of ‘behavior,’” just “one form of a vast interconnecting formal and cosmic dynamic.” Being more influenced by natural science than by music history, Cowie believes that music is also “an expression of both conscious and unconscious sensitivities to sound” based on “sound, color, order, disorder, shape, pattern [and] form.” Yet, as he puts it in the liner notes, “After many decades of acting on those beliefs and impulses, I continue to encounter opposition or total incomprehension to or of my music. This is not true of an increasing number of wonderful musicians who clearly love the same kinds of journeying as I do and of a burgeoning audience who seem to understand that my music is both natural and of nature.”

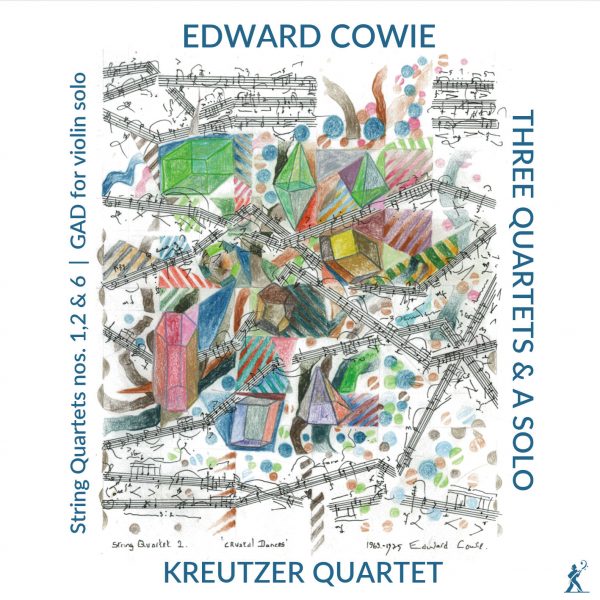

As an artist, Cowie makes “preliminary sketches” for his music.

Unlike some other hitherto undiscovered British composers like Barry Mills, whose music is also nature-driven but who writes in an essentially tonal form, Cowie crosses the border into atonalism more frequently. Yet, at the same time, I hear in his music much of the same sensibilities that I hear in Mills’ scores, an evident desire to present his reactions to the world of nature through music. It must be a British thing, as quite a few such composers going back to Frank Bridge have done the same thing in varying degrees of success.

Perhaps what his “opposition” finds upsetting about Cowie’s scores is their apparent lack of thematic continuity. I noticed that he enjoys juxtaposing themes more than following a logical order, but this was also a feature of Peter Maxwell Davies’ late music. Indeed, what I like most about Cowie is his lack of predictability; he clearly relies on his own impulses and reactions to the natural world, and thus tries to “compose” that natural world in his scores.

Another reason why I like Cowie is that his own reactions to nature seem to arise from impulses of the moment. This, too, contributes to his lack of predictability in his scores. It also keeps the listener fully engaged in his musical journeys; you don’t want to miss anything, so you keep on listening. I should point out, however, that although he delights in the juxtaposition of themes, his music is not incoherent or abrasive in the way, for instance, that Penderecki was abrasive. He is inspired by the moment, yet he knows how to tie those moments together to produce music that is coherent.

If anything, his second quartet, subtitled “Crystal Dances,” is even more diverse and imaginative than his first. It seems to consist of jagged shards of music that intersperse with edgy but lyrical passages, moving along at its own pace and filling time in its own way. The playing of the Kreutzer Quartet is wonderfully responsive to the demands of this music, maintaining a light feel but a very bright timbre in all four instruments so as not to miss any of the jagged sparkles that emanate from his scores. I liked this second quartet very much for its startling unpredictability. In the latter part of the quartet, Cowie uses fast upward portamenti for the strings as an expressive device.

The second and sixth quartets are broken up by the violin solo, GAD, which is autobiographical, since Cowie has been suffering from General Health Anxiety Disorder since he was 15 years old. The music is even more fragmented and tense than the preceding quartets, and is played expertly by the Kreutzer Quartet’s first violinist, Peter Sheppard Skærved.

The sixth quartet is different from the first two in that it is longer (approximately 21½ minutes as compared to 14 and 17, respectively) but also that it is divided into four movements, each one representing different seasons. The first movement is titled “West Wind: Autumn,” the second “North Wind: Winter,” the third “North Wind: Spring” and the last “South Wind: Summer” (so apparently they don’t have an east wind in England) **. Like Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, the music is descriptive, but I would go so far as to say that it is more definitively descriptive than Vivaldi’s generic sound pictures of each season. Vivaldi gives one the impression of the feelings one has in each season, whereas Cowie gives you a musical approximation of the way weather unfolds in each of them. The music here is tighter in structure than the previous two quartets, possibly because Cowie was thinking as much if not more about the structure of each movement in and of itself rather than the layout of the piece as a continuous evolution. One can compare, for instance, the series of string tremolos that opens Vivaldi’s “Winter” to the much edgier, almost abrasive string tremolos that open Cowie’s vision. The latter is harsher, less tonal and “feels” more like vicious gusts of icy wind, following which the more legato passages imply the frozen-in-place landscape that ensues. Interestingly, “North Wind: Spring” doesn’t feel the least bit spring-like in the opening, which consists of swooping downward portamenti that almost sounds like the temperature dropping instead of rising, which repeat themselves later on. Summer is also represented by string tremolos, but much further down in the instruments’ range, softer and more sultry in character.

** The reviewer did not read the track list carefully: the third movement is indeed East Wind (Spring)!

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978