The Consort

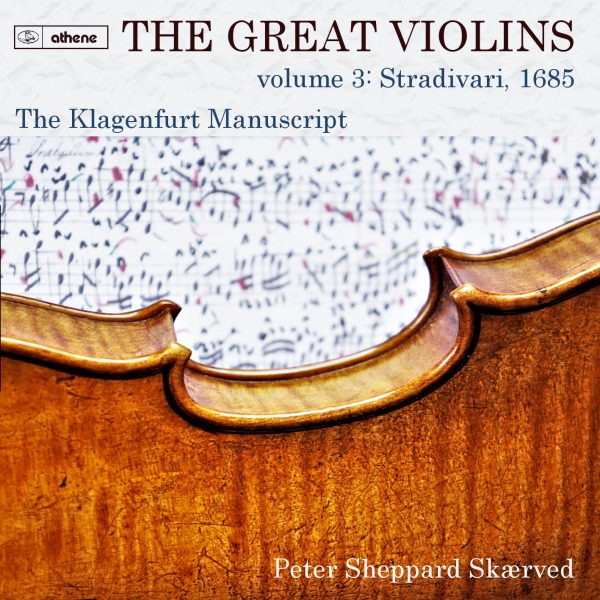

This new CD pair, over 140 minutes’ worth of music for unaccompanied violin, continues Peter Sheppard Skærved’s two-pronged exploration of early violins and the early violin repertoire, matching up characterful early instruments (and carefully selected bows) with well-suited, often little-known pieces. The present offering is a marriage made in heaven. On the one hand, we have a violin of unusually small dimensions made by Stradivari (and dated 1685) from the collection of Historical Musical Instruments at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, which is complemented by a small bow from the modern Genoese maker Antonino Airenti; on the other, we have the entire content for unaccompanied violin (there are also ensemble pieces) from a large volume of music from exactly the same period, originating from the Habsburg domains and known today as the Klagenfurt Manuscript.

Its present location is the Landesmuseum Kärnten in Klagenfurt, but it was formerly in the possession of the nuns of the not too distant Benedictine abbey of St. George at Längsee. The pieces are all anonymous and often also untitled. Their idiom and in particular their employment, for the unaccompanied items, of scordatura, dance and variation forms and the peculiarly Germanic stylus phantasticus (a rhapsodic, quasi-improvised manner) link them firmly to such composers of the Habsburg domains as Schmelzer, Biber, Westhoff, Walther and Vilsmayr, and perhaps to Biber in particular. Sheppard Skærved speculates, though without providing evidence, that the manuscript was composed and copied out by one of the nuns. This is impossible to disprove, but an alternative hypothesis would be that it is the work of a male violinist-composer who, or whose heirs, donated it to the convent.

The almost 100 unaccompanied pieces nearly all last in performance no less than one and no more than two minutes with every repeat played. Some form natural suite-like groups linked by key, the use (or not) of scordatura, and the type and sequence of movements (a movement titled Praeludium naturally stands at the head of a group and a Finale at its end); other pieces are apparent singletons, although very often these are includable ad libitum in a group.

A case in point is the eighth item on Disc A, a gigue-like movement in A major employing the scordatura tuning A E a e (reading the pitch of the strings in an upwards direction), that shares this key and tuning with items 1-4. Items 5-7, which employ normal tuning, form a separate three-movement suite in G major. Sheppard Skærved argues convincingly that the volume is a composition manuscript in which the order of the works written down by their author reflects, at least predominantly, their sequence of composition. Thus it could well be that item 8 is separated from items 1-4 merely on account of being a late addition.

In all, five different forms of scordatura appear: G D a d, A D a d, A E a d, A E a e and

D F a d. In his thoughtful, incisive and experience-based booklet note – worth publication separately in some form as a journal article – Sheppard Skærved emphasises how the purpose of scordatura is notmerely to bring different chordal combinations or open strings into play (or to facilitate imitation of passages at the octave, as the symmetrical A D a d and A E a e tunings do) but, as a result of resetting the internal tensions in the instrument itself, scordatura alters the whole timbre and sonority of the violin, creating in effect a different instrument. This thesis is brilliantly borne out in his performances.

Their pedagogic value apart, these two CDs are not easy to listen to from start to end in a single sweep. The composer has difficulty inventing memorable ideas, and the tonal trajectory of movements and their internal pattern-making can sometimes seem primitive or clumsy. But occasionally there is something genuinely arresting: for example, the fierce and passionate courante-like movement (item 46 on Disc A) which ends a group in D minor that employs the closely-packed tuning D F a d. Probably, the best listening strategy is to choose small clusters of pieces at a time.

The performance is hard to characterise. So many of the pieces are ‘over before they have begun’ that it is hard for Sheppard Skærved to develop a narrative. One can at least say that the playing is accurate and stylish, bringing out effectively the protean qualities of the Stradivarius instrument. I personally would have preferred a less frequent use of rubato: it is so much easier for an unaccompanied player with the music in front of him or her to retain a sense of metre and pulse than it is for a listener without that advantage.

Many possible exploratory paths lead out of this fascinating recording. To investigate further the provenance of the volume and the composer of the music (perhaps the ensemble pieces offer clues?) is an obvious task. A comprehensive study in book form – historical, technical and aesthetic – of the entire phenomenon of ‘alternative tunings’ on the violin, perhaps also taking in traditions and locations other than those of Western art music, would recommend itself. The recording is perhaps not for everyone, but it and the accompanying booklet have much to teach students of organology and violin-making, devotees of the South German-Austrian-Bohemian school of violinist-composers and anyone interested in the history of the partita or suite and its constituent movements.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978