Musical Opinion

Froberger may have come to be less neglected than he once was, with Thurston Dart’s 1961 recording (also on clavichord) and the recent quatercentenary in 2016 being significant fillips, but it is a contention of this recording project that this revival has often taken place rather unevenly and incompletely. The toccatas and suites, and above all the occasional pieces (the laments, the tombeau, the programmatic works) with their clear emotional pointers, have all been widely programmed and recorded:, but the contrapuntal works, roughly equal in number to the others and certainly given equal prominence in the autograph manuscripts, have been largely avoided. It is as if many performers want to mix the cocktails and pour out the spirits, but are wary of decanting the fine wine that comes in between.

Six of the eight fantasias and all six of the canzonas were gathered by Froberger himself in his sumptuous Libro Secondo of 1649 (the Libro Primo was lost, so this is some of the earliest music we have by Froberger), where they are presented after the six toccatas and before the six suites — to stand as the heart of the matter. Superficially similar examples of their respective conventional forms (one reason for their relative neglect?), they embody in fact a diverse range of treatment — perhaps, with the later ricercars and capriccios, the fullest and profoundest compendium of keyboard counterpoint before J.S. Bach.

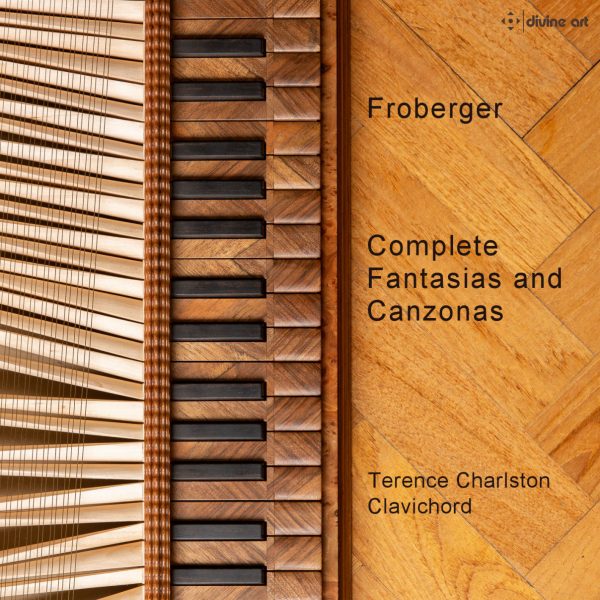

Terence Charlston has chosen for this recording a most unusual clavichord, reconstructed by Andreas Hermert as a posited earlier state of an anonymous fretted clavichord surviving in the Berlin Musical Instrument Museum (MIM2160). Its sound and capabilities are remarkably well-suited to Froberger’s textures, and fully capable of doing justice to both intricacy and a continuing sense of line, across a spectrum of tempi limited here only by the exclusion of extremes. It can sing and it can dance; its colours can match the wide range of affect within these pieces, and any worry that a disc like this might become monotonous is repeatedly dispelled by the trio Froberger-Hermert-Charlston.

The playing is exemplary in its avoidance of anything either doctrinaire or gratuitous. Each piece is taken on its own terms, grounded in deep and patient understanding of its characteristics. Some are presented almost literally, with little added ornamentation, while in others embellishment is given freer rein, but never so as to impose anything alien. The execution of written-out ornaments frequently stays very close to the notation, as if to trust that Froberger knew what he was writing — not always the impression that performers give. (Perhaps Froberger’s famous reluctance to share his manuscripts with other musicians stemmed less from a belief that they wouldn’t know how to vary and embellish his music, but that they would do so too much.)

One of the most delightful features of this recording is the treatment of the ends of the canzonas. Here Froberger frequently allows the boughs of his polyphony to blossom into something like the stylus phantasticus of the toccatas. It is possible here for a player to be seduced by the sense of freedom into losing contact with what has gone before, and a particular challenge of presenting all of these pieces side by side must be that any personal formulae or mannerisms would become starkly apparent. Terence Charlston deftly and gracefully adds just what is needed, presenting what Froberger gave us with just enough spontaneity to make the experience a constantly refreshing one. This is very fine playing, beautifully recorded in the Royal College of Music Studios, and anyone who knows that music is a matter neither of the head nor of the heart alone deserves to listen to it.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978