Fanfare

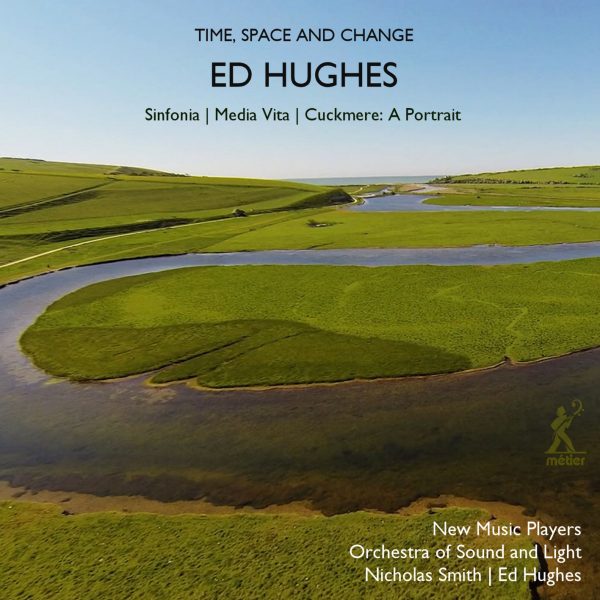

In 2012, I thoroughly enjoyed a Metier twofer of music by Ed Hughes (Fanfare 36:2). He is well known for his film music, and indeed Cuckmere: A Portrait (2016-18) was originally conceived as a live score for a film by Cesca Eaton. The idea was to portray a year in the life of a river (the River Cuckmere); the area called Haven that is an undeveloped flood plain in East Sussex, characterized by chalk grassland. There are four main movements, one for each season, plus interludes and a short, jaunty Prelude. The music rarely slows (“Cuckmere” means “fast-flowing” in Old English), although “Interlude I” contains a distinct feeling of easing. It would be wrong to describe Hughes as Minimalist, but there are perhaps ghosts of Minimalism in his machine. When “Winter” opens into a piece of clear, tonal nostalgia, the effect is remarkable; it is exquisitely placed and delivered with real sensitivity by the Orchestra of Sound and Light. Hughes’s achievement is to carve something perfectly crafted from a wide-ranging harmonic vocabulary. His ear for sonority is remarkable: The threadbare, slightly discombobulating “Interlude III” is simultaneously beautiful and disconcerting. Given that the composer himself conducts the orchestra he co-founded with producer Liz Webb, The Orchestra of Sound and Light, this recording has about as much authority as it is possible to accrue. This is that rare beast: uncompromising music of our time that will raise a smile. Even the very final chord, in its delicious ambiguity, has a wry twitch of the lips about it.

The staggeringly beautiful, 20-odd minute motet by John Sheppard Media Vita was the starting point for Hughes’s 10-minute piece of that name for piano trio. Hughes’s own Media Vita was premiered by members of the group Ixion at Brighton, UK (specifically the performers then were Michael Finnissy, piano—himself one of Hughes’s teachers—Charles Mutter, violin and Zoe Martlew, cello). Shadows of a cantus firmus seem to flit in and out of focus; all three players wring every molecule of emotion from Hughes’s dense score. Here, Richard Casey is clearly a remarkable pianist (there are quite some demands) while Suzanne Stanzeleit and Joe Giddey’s lines entwine, vine-like.

Another response to earlier music is the Sinfonia. The first movement, “Agincourt,” takes an anonymous English folk song of the early 15th century, the second, “Stella Celi Extirpavit” takes a motet from the Old Hall Manuscript by John Cooke, the text of which is a plea to the mother of God to save populations from the effects of a plague. A motet by John Dunstaple forms the launching pad for “Veni Sancte Spiritus,” which includes moments that veer towards English pastoralism (performed gloriously here by the New Music Players). It is Tallis who informs the flowing, illuminated “In iejunio et fletu,” and Gibbons, in one of the most famous English madrigals of them all, The Silver Swan, who forms the shadowy foundation for the penultimate movement. Finally, there comes “In Nomine”, a movement based not on a particular instance but on the genre of In Nomines, one which also finds room for the cry of a London lavender seller from the late 1930s and a children’s game song. The effect is quite happy-go-lucky, brilliantly performed by the New Music Players (an¬other ensemble founded by Hughes). This is proof positive that modem music can convey joy.

Superb notes by the composer himself add to our appreciation of this beautifully recorded, fascinating music. The more I hear by Hughes, the more I am intrigued. It is simply astonishing to find out that these recordings are live, such is the unanimity of the performances.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978