Fanfare

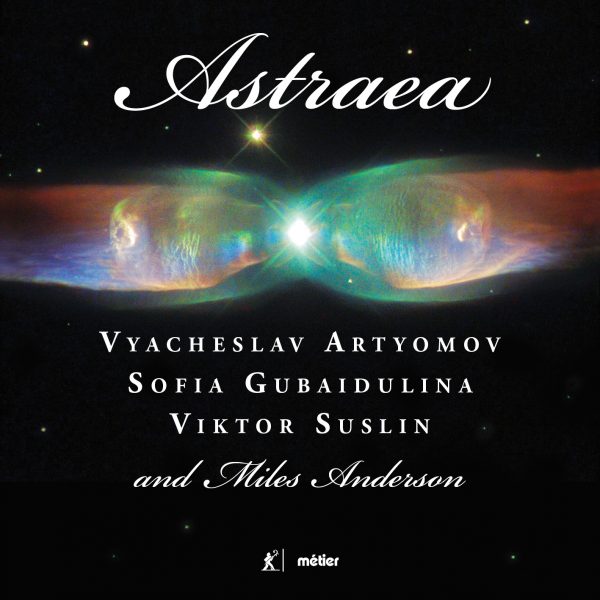

In Greek mythology, Astraea was “the virgin goddess of justice, innocence, purity and precision” (Wikipedia). The Astraea Ensemble is an improvisatory group founded in 1975 by three Russian composers, Vyacheslav Artyomov, Sofia Gubaidulina, and Viktor Suslin. They play “eastern and Transcaucasian” instruments:

Duduk: Double-reed wind instrument, rather like a soft-toned oboe.

Salamuri: Higher pitched wind instrument, a cross between flute and piccolo.

Tar: Four-stringed Persian instrument, softer than a ukulele.

Kiamancha: Bowed Azerbaijan/Persian string instrument.

Chonguri: Plucked Georgian string instrument.

Kanon: Many-stringed instrument, like a large zither.

The names sound like eastern versions of Harry Partch’s home-made instruments. Astraea also plays a mandolin and “various types of drums, bells.”

The credits for this disc are confusing, the headnote a best guess. Is Archipelagos of Sounds in the Ocean of Time true improvisation? Artyomov’s program notes (translated from Russian) are in¬decisive: “At first, we … concentrated exclusively on spontaneous, previously unprepared improvisation…. Performances in front of the public violated these conditions [why?], demanded ‘performance,’ and not creation, and it was necessary to relinquish that in favor of studio recordings.” Relinquish what? Public performance or improvisation? The opening two minutes consist of soft tapping on drums and perhaps other percussive materials (no duduk, no salamuri, no tar, no kiamancha, no chonguri, no kanon, no mandolin). Bit by bit, other instruments join in, two or three at a time (I gather there are three performers), including some low brass not mentioned above—are those elephants trumpeting in the distance? The dynamic level remains low, the pace relaxed. Some instruments are placed exclusively in the right or left channel, as with early stereo ping-pong LPs. This could very well be improvisation by musicians who know each other well; it’s sometimes jazzy, sometimes like being lost in a Hollywood jungle film. One would love to have a video to match the sounds to the instruments. Archipelagos is an interesting potpourri, but it took some patience to get through its 26 minutes, which I’m not inspired to repeat.

Continuing to confound expectations, we jump from no composer to three. The cacophony (to our ears) of Eastern instruments continues, but longer-held notes by both strings and winds offer a sense of continuity, even direction, although the music is not as soft or sweet as the title Dolcissimo suggests. As in Archipelagos, little of the characteristics we associate with music—tonality, melody, rhythm—remain. If there is structure (repetition), I do not hear it. Yet the three composers have created something almost elemental that grabs and holds one’s attention; it’s a big step forward from Archipelagos. It is difficult to judge recorded sound when one is unfamiliar with the instruments; the abnormally wide stereo spread remains, and the percussion are startlingly clear for 1977 and 1980 Russian recordings.

By 1988, American trombonist Miles Anderson had joined Astraea; he and Artyomov collaborated on Death Valley, recorded in California. It is “also an improvisation, with a very small amount of set arrangement”—not so small, to these ears. The group’s aesthetic continues, but the presence of some Western instruments and electronic processing make it more comfortable. As the piece heats up, there is a suggestion of a wild sort of Minimalism: repeated phrases, slowly altered. There appear to be vocal contributions, well disguised by electronic processing. The whole elicits grander scale than the earlier works, more suitable perhaps to California than Moscow. Death Valley expires in a long, slow pp coda, followed by less than a minute of a poem spoken in German.

Heartily recommended, but only to the most adventurous listeners.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978