Fanfare

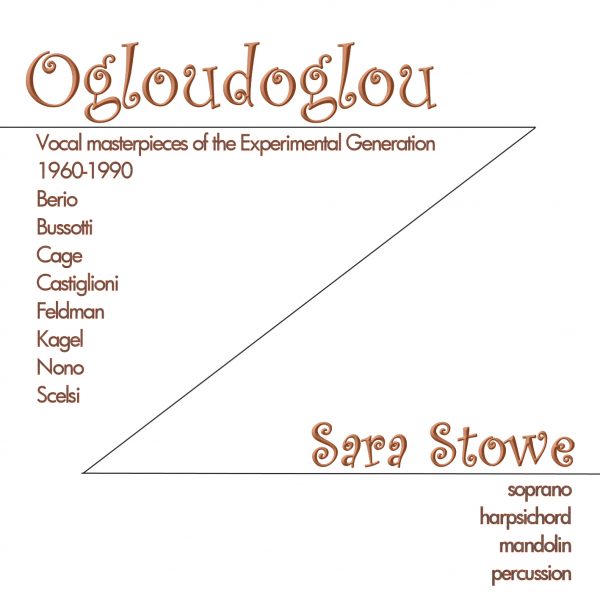

This is an astonishing display of vocal virtuosity. The trailblazing lights of Cathy Berberian and Michiko Harayama enabled the creation of a whole new repertoire. Of course, there is Berio here, and Cage, but also so much more.

The short Taiagaru No. 4 is archetypal of this expressive world (the entire Taiagaru is subtitled “Five Invocations”). Words are divided into syllables, and themes seek to form themselves interrupted by staccato outbursts, as the whole is dispatched with consummate mastery by Sara Stowe. The complete Canti del Capricorno, previously been recorded by Harayama on the Wergo label, is here represented by the eighth part, surprisingly rhythmical at its opening. First performed in Paris it 1969, Ogloudoglou requires the performer to play percussion as well.

It’s unsurprising that John Cage should make an appearance here. The storytelling in Sonnekus is remarkable, especially when heard via Sara Stowe’s voice. The work was written in 1985 for the first meeting of The Satie Society. Sung minus vibrato to invoke a folkish atmosphere, it can be performed as a stand-alone piece (as here) or interspersed with cabaret pieces by Satie.

My first experience with the music of Sylvano Bussotti was a shattering and defining one, a DO LP of Bergkristall with the North German Radio Orchestra Hamburg conducted by Sinopoli (subsequently rereleased in a Bussotti CD box). It is a magnificent work, and Stephen W. Ellis seemed to find much to enjoy in it also, if we are to believe his review in Fanfare 5:5 (1982). Bussotti’s Lachrymae is a graphic score, part of which is reproduced in the booklet. In this “semi-prepared” performance, Stowe delivers the vast intervallic stretches, speaking in four languages (Italian, French, German, and English) with great assurance. The text is mobile, too, as both the words sung and their order can vary tremendously. Stowe is asked to utilize a variety of vocal effects, including panting and cackling, which she does with consummate assurance—not quite the cataclysmic effect of Bergkristall, obviously, but intriguing nonetheless. Stowe’s purity at the extreme top of her register, coupled with her extreme assurance of pitching, plus a lovely glistening aspect to her voice, makes this reading a bull’s eye.

It was for Berberian that Berio wrote his Sequenza III, and all singers are obviously in her shadow. All credit is due to Stowe for a performance of supreme virtuosity (much is fast), but also one that holds silence in an almost Webernian sense of the holy, an integral part of the music’s fabric. The singer is also required to play the harpsichord in Kagel’s Recitativerie (sometimes also found as “Rezitativerie”) as part of the drama and theater. The music quotes and then deconstructs the left hand of Chopin’s Nocturne in C Minor, op. 48/2. The voice plays at times with our expectations of the cantabile right-hand melody; at other times the chords themselves go for a walk.

It’s little surprise to hear the voices of Italian workers in an industrial plant in Genova via tape in a piece by Nono, his La fabbrica illuminata. The musical surface here is forbidding, even at times frightening. Stowe’s achievement, apart from sheer stamina, is to maintain the atmosphere throughout. Part of this axis of composers is Nicolo Castiglioni. Rosbaud’s performance of his Sequenze for orchestra has a fair currency; a recommended other point of call is Neos’s superb disc devoted to his music, the pieces Le favole di Esopo and Altisonanza. His Cosi parla Baldassare is a setting of part of Baldassare Castiglione’s Il corteggiano (The Courtier), a book on etiquette and morals published in 1528. As with the orchestral disc cited, there is a pronounced strain of Italianate lyricism. Stowe manages beautifully the registral demands placed upon her (that comment also applies to most of the pieces here, in fact). An English translation of Rilke’s “Sonette an Orpheus CCIII” is used for Feldman’s appealing Only before the final item, Scelsi’s CKCKC for voice and mandolin. It’s quite an achievement to play the quite involved mandolin part.

Booklet notes are pithy but informative, although a little more detail on the Scelsi pieces would have been appreciated. That is hardly enough to detract from a wholehearted recommendation, though.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978