British Music Society

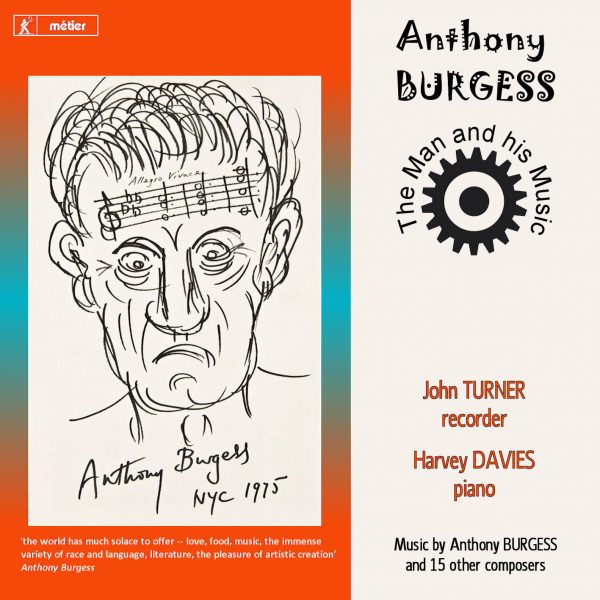

Ned Rorem, 97 in October, has always said he is a composer who writes, while Anthony Burgess always wanted to be seen as one too. Alas, such were his achievements in literature that he has, and on the showing of the compositions here, always will be seen as a writer who composed.

Burgess was self-taught as a composer, and few of his 250 plus compositions were heard during his lifetime. That he had a good inner ear is undeniable from the sound of his works, but he was no innovator and while he had the technique to notate his music, he did not have the level of inspiration to rise above the mundane.

The notes here also show him to be a puzzling man. All of the works were written for his son who was apparently a mediocre recorder player, but they are all so difficult it is unlikely he could have played them. Indeed, some exceed the lower and upper range of the specified instrument and so have had to be adapted for multiple recorders, not just one. Why would Burgess père do that?

All of Burgess’s works, the earliest from 1990 are reminiscent of the British recorder works of 50 years earlier, tuneful, pleasant but inconsequential. Of the other 15 composers some, Josephs, Seiber, Crosse and Rawsthorne are known while the others are not. They all, like Burgess, write well, the Dubery and Pope works are fun, but are all interchangeable in style and utterance.

Listen to the great works for recorder by Jacob, Berkeley or Arnold, to see what inspired musicians can do with the instrument. Beautiful constructions, beautiful playing, beautiful recordings, but even after a number of listenings I am afraid none of the music sticks in my ear.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

We noticed you're visiting from Latvia. We've updated our prices to Euro for your shopping convenience. Use Pound sterling instead. Dismiss

![🎧 Listen now to the @purcellsingers' first single from their upcoming album, #ASpotlessRose! ➡️ listn.fm/aspotlessrose [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/642752592_1424641949105789_8815810652567824072_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzMifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=aY1NGfNpOoYQ7kNvwEXZYzC&_nc_oc=AdlbjDz3zyFj5WLfX1Q9_OAPAiCLbWmMjzwtsYrQ0yDIv8RWk7cfWBAbqds2XLjHl64&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-2.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=aKOGd4IcCy-qJ2MTgnncVQ&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQFVZOrw38QL7XAUFlXey3Mc-NOtBZt8Qmvk_N2toL7D2T42jvNEQs1gt2JruVmdoUNkDKWZJCyz7g&oh=00_Afw2_aI3ATMncYANNAJzjdeCnqwAEILkf93PsW-D0srfRw&oe=69AE2BC1)