Fanfare

In 1992 at a music festival in Nottingham, a one-of-a-kind stage work premiered. At its core was the musical work preserved here, recorded in a London studio that same year, whose title, The Roaring Whirl, comes from Rudyard Kipling’s adventure novel Kim. More than an East-meets-West encounter or the belated gasp of empire, The Roaring Whirl recreated a world of Indian color, music, and dance. It must have been a heady spectacle, more serious than Bollywood but just as kaleidoscopic.

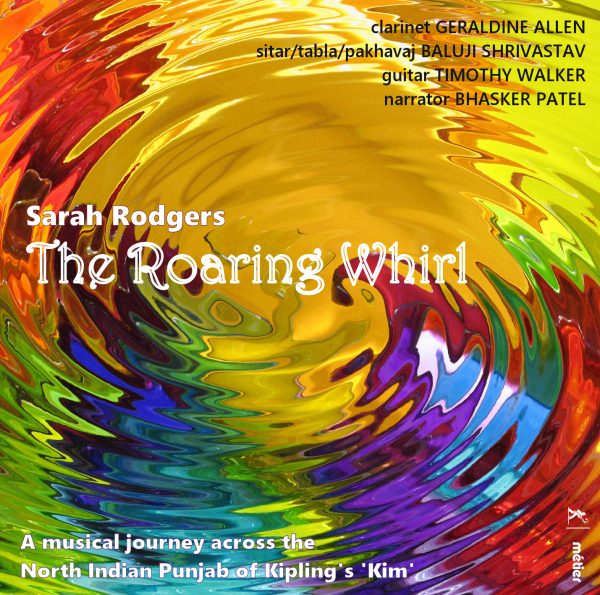

On audio disc the experience is diminished by half—it’s a shame the visual spectacle wasn’t recorded—but what remains is uniquely intriguing. The ground plan is a journey that the novel’s young protagonist Kim takes alongside a wandering holy man, the Lama. There are seven episodes, each preceded by a thematic narration with titles like “India Awakes” and “Seventh Heaven” filled with Kipling’s ripest exoticism The musical content consists of ragas with specific meanings that the British composer Sarah Rodgers uses as her own jumping-off point for an original composition. The result belongs very broadly to the genre of world music, but with unusual angles that I was curious to experience.

To begin with there is Kipling’s writing, which I’ve read since childhood acquaintance with the Just-So Stories. Many today raise their eyebrows at the notion that Kipling, a tremendously popular writer with imperial attitudes and racist beliefs, should have received the 1907 Nobel Prize in Literature. But his gifts of language, imagination, and colorful evocation are unassailable. Rodgers sets three of the seven movements in the bustle of a festival and market life in Kashmir and three in the hills where Kim reflects, with the Lama’s guidance, on the nature of life. A central episode, “The Roaring Whirl,” depicts Kim himself, using a color wheel (essential in the stage work) to depict the beautiful disarray of India as well as the Lama’s view of life as a perpetual round of reincarnations.

The musical side is grounded in seven classic ragas performed by acclaimed sitarist Baluji Shrivastav, who is remarkably versatile; he also plays two Indian percussion instruments, the tabla and pakhavaj (a horizontal two-headed drum). Each raga is named, beginning with Vibhasa, whose meaning is given as “bold like the god of love.” For each raga there is a denoted expression and appropriate time of day. For Vibhasa, the expression is “lively, energetic, challenging,” suited to morning as the time of day. On the Western side the instruments are the guitar, performed by Shrivastav’s duo partner Timothy Walker, and clarinet, played by the commissioner of The Roaring Whirl, Geraldine Allen.

Decades have passed since Yehudi Menuhin and Ravi Shankar had a hit with their West Meets East LPs, and the air of hippie complacency has soured in the face of political turmoil and terrorism. Kipling is so beyond the pale as far as political correctness goes that even for a listener who loves his prose, the depiction of the Lama’s stereotypical Indian fatalism causes some wincing. But Rodgers has a strong interest in Asian and West African music, and she has immersed herself in this cross-cultural project as a continuation, one might say, of Holst’s earlier immersion in Indian spirituality. There is a “body, mind, and spirit” ethos to The Roaring Whirl, too, which feels consistent with Holst’s Savitri and Hymns from the Rig-Veda.

I regret that it takes so much space to describe the setup for this piece, because the effect on the listener is immediate and pleasing. Kipling’s words are expertly narrated by Bhasker Patel, a well- known television actor at the time; he sees the world through the innocent, wondering eyes of Kim and makes us see it that way, too. Rodgers’s music, which makes space for improvisation, is harmonically about the same as Holst or West Meets East, and the sitar sits comfortably beside the fairly basic but colorful clarinet and guitar parts. Nothing is “too Indian,” if that is your concern, but there are a few issues. First is the untutored Western ear, which doesn’t hear the differences expressed through various ragas; they tend to remain consistently foreign. There is also a certain sameness to Rodgers’s idiom, and finally, a length of more than an hour exhausts the listener’s attention span without the stage spectacle.

I didn’t feel these drawbacks keenly, although they tended to mount up after half an hour or so, end in essence The Roaring Whirl is accessible and appealing. I recommend it to anyone who appreciates Kipling or who has a nostalgic yen to travel back to the heyday of the Raj wearing Romantic eyeglasses.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978