Fanfare

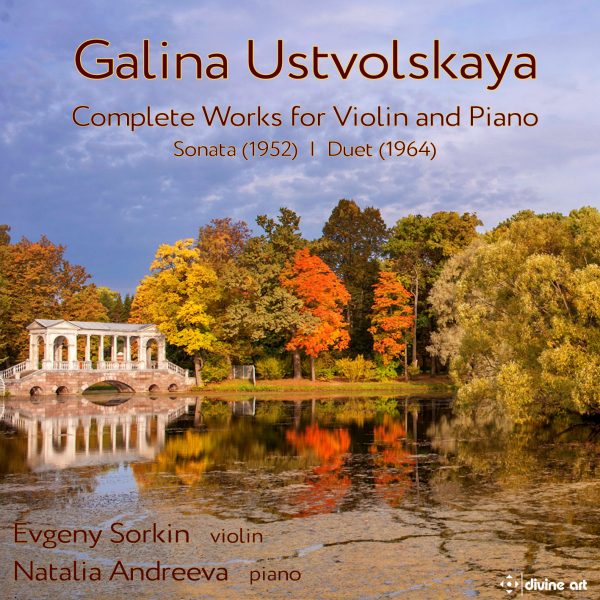

Galina Ustvolskaya (1919-2006) wrote just two works for violin and piano, and both of them have been recorded here. This is a somewhat short program, but it gives value for money, as both of these works demand much from the listener, and should not be taken lightly. How she was able to get away with writing such music during the eras of Stalin (the Sonata dates from 1952) and then Khrushchev (the Duet dates from 1964) is hard to fathom. She was taught by Shostakovich (who wanted to marry her, although she refused). He came to admire her music, and he even included quotes from it in his later works. However, by 1952, she had largely gotten his music out of her system. Indeed, at one point she commented that, “There is no link whatsoever between my music and that of any other composer, living or dead.” Listening to her mature works, one can well believe it — she sounds like no one else, for better or worse.

Still, the Violin Sonata has not yet turned its back entirely on the world; to me, it is not quite a mature work, although by saying so I am not trying to denigrate it. Pianist Andreeva’s heavily foot- noted booklet notes discuss both of these works in detail, including notations in the published scores that seemed unclear to the performers, and that necessitated going back to the composer’s manuscripts. For Andreeva, and I assume for Sorkin as well, the sonata is about Stalinist terror. It plays chess, if you will, in a gray, washed-out terrain where only a few moves remain possible. In the coda, where the violin steadily plays col legno, Andreeva hears the dreaded knocking of the secret police on the door. It’s a harrowing work, but still a human one.

The Duet, even more fragmented and confrontational, goes off the deep end, and any semblance of what one might describe as a sonata crumbles into dust. Tone clusters, extreme dynamics, extreme registers, and violent gestures converge to create an alienating environment. At many points, one or both of the instruments grab motifs as a drowning man grabs a lifesaver that has been thrown to him, and then they repeat them obsessively until the notes turn black and blue. Gears grind and teeth gnash. At other points, the silences between the notes loom, as if Morton Feldman had been transported to a gulag. The closing section, where the violence abates somewhat, sounds almost like balm, but that is only in relation to what preceded it.

Both of these works were recorded by Patricia Kopatchinskaja and Markus Hinterhauser for ECM New Series. (They throw in the 1949 Trio for Clarinet, Violin, and Piano, with clarinetist Reto Bieri, for good measure.) Robert Carl give that disc a very high recommendation in Fanfare 38:4, and indeed, Sorkin and Andreeva seem to have had their work cut out for them when they approached this project, although neither of them are newcomers to Ustvolskaya’s music. (In fact, Andreeva’s doctoral thesis was devoted to Ustvolskaya’s music, so she knows of what she speaks, and plays.) It is fascinating to compare these two recordings, because the performers interpret Ustvolskaya’s markings, particularly in the Duet, in very different ways. For me, the difficulty lies in not knowing which is the correct way, but the answer to that problem might be to say that they both are effective. Just listen to the first minute of the Duet and you might be unsure that you are even listening to the same work. If anything, however, Kopatchinskaja is even more terrifying than Sorkin, as her violin seems to be living in a tonal nightmare from which it cannot awaken. On the other hand, I like Sorkin’s more wiry sound in the sonata, and also the way both players work to extract expressivity from the music’s frequent cul-de-sacs. Maybe you had better get both discs. But whatever you do, do get at least one of them!

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978