Arts Desk

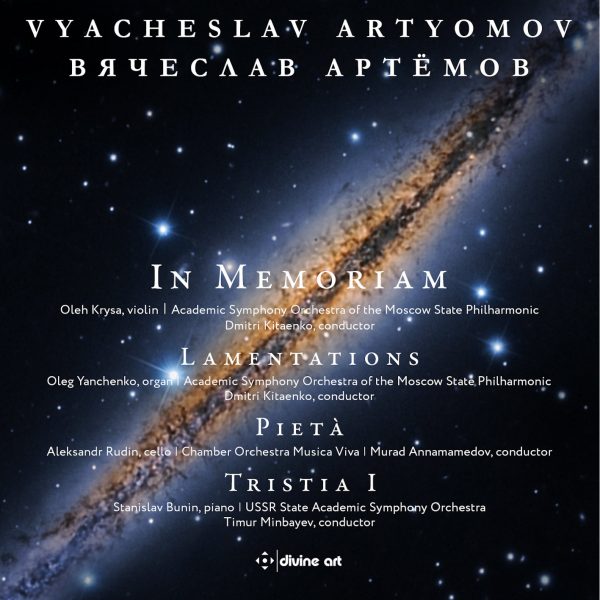

Born in 1940, Vyacheslav Artyomov trained as a physicist before switching to music. He joined forces with fellow composers Sofia Gubaidlina and Viktor Suslin in the mid-1970s to form a group specialising in improvisation with unconventional instruments. Like Shostakovich and Prokofiev before him, Artyomov fell foul of the Soviet authorities, his music effectively banned for several years. Though Tikhon Khrennikov, the famously cantankerous chief of the Composers’ Union, performed a volte-face a decade later and declared that Artyomov’s 1988 Requiem “raised Russian music to a previously unattainable height.” Three sections of that work were transcribed by Artyomov to form Lamentations, the choral parts now played on organ. Angst-ridden and ecstatic, it makes for compelling listening, and it’s prompted me to seek out the source work.

There’s a sameness of tone to the pieces collected on this latest volume in Divine Art’s ongoing Artyomov series: this music is slow and sombre, the lightness achieved through transparent scoring. Writing slow, serious music never hindered Pärt or Tavener, composers who share Artyomov’s Christian faith. These pieces are worth hearing, and a useful introduction to a figure who deserves wider recognition. In Memoriam began life as a violin concerto written in Artyomov’s twenties, later reworked as a single movement symphony. Some of the solo line survives, beautifully played here by Oleh Krysa. Pietà is an extended work for cello, strings and tubular bells, rich in angular melody and full of striking effects. And there’s Tristia I, a downbeat concertante piece for piano, strings, trumpet and vibraphone which defies our expectations of what a work written for those forces should sound like. The performances are authoritative and well-engineered, several of them recorded back in the 1980s when Artyomov was officially out of favour.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978