Fanfare

Confused? You will be. There are two female composers called Carlotta Ferrari, and to make matters worse, both of them studied in Milan. The present one was born in 1975 (the other’s dates are 1837-1907). So putting “Carlotta Ferrari” in the headnote hardly helps.

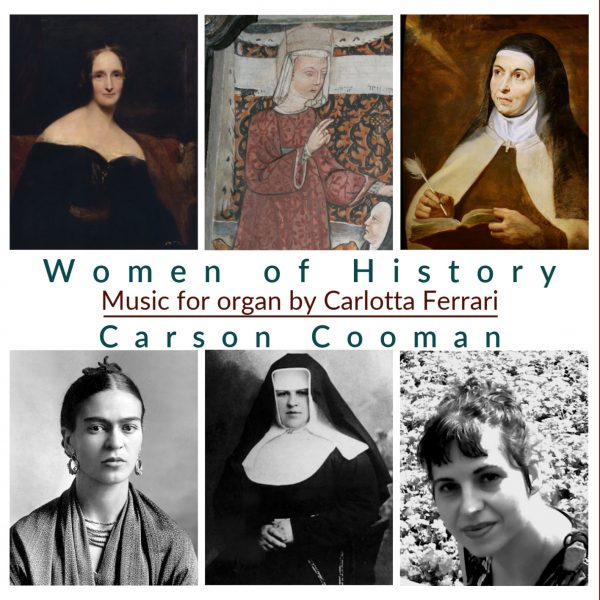

The present disc is entitled Women of History. All five works herein are inspired by the live and works of significant historical ladies. Ferrari’s music has a modal bent: She has worked with a system called “RPS” (“Restarting Pitch Space”), explained eloquently and in detail by its founder, the organist here, Carson Cooman, at carsoncooman.com/restarting-pitch-space. Perhaps what is important to grasp is the limited transpositions within sets and the general modal feel.

The first piece, Lady Frankenstein (2016), is a symphonic poem for organ cast in four movements and inspired by Mary Shelley, the literary creator of Frankenstein. Fascinatingly, the composer sees the monster as a projection of Mary Shelley’s feelings of guilt, loss, and anger. The piece begins with the slow-moving “organo pleno” chords of “Mary e la Creatura.” There is certainly a Gothic at¬mosphere to the super-long pedals and imposing chords; a more supplicatory “Imperare la vita” (Learning Life) which seems to be suffused with a sense of awe prior to its agitato 16th notes, follows. The chorale-like sections keep on returning in this movement, almost projecting a sense of hesitant exploration. Cooman offers performances of the utmost respect to the score, and the organ (the main organ of Laurenskerk, Rotterdam, Netherlands) is spectacularly caught by the engineers. The work’s third panel, “L’amore,” is a gentle “Passacaglia in Trio”; the repeated chords of the finale, “La morte it ghiaccio, nel fuoco, nel mare” (Death in the Ice, the Fire, and the Sea) take the work into a very different space: Some sort of comfort, albeit a sadness-laden one, is heard at the very close.

The piece Maria Restituta (2016) is subtitled “Rhapsody for organ” on the score and is dedicated to the memory of Maria Restituta Kafka (1894-1943), a Franciscan nun and nurse in Vienna who was executed by the Nazi authorities after satirically mocking Hitler in a poem and refusing to remove crucifixes from hospital rooms. In 1998, she was beatified as a martyr. The mode here is Lydian beginning on D. References to church cadence are part of the musical vocabulary here. A faster section (headed simply “Mosso”) attempts to bring movement and maybe even to leaven the mood, but to little avail. Gesturally simple, the piece actually makes for a poignant effect.

Like the first two pieces, Historia Gullielmae dates from 2016. And like Lady Frankenstein, it is a symphonic poem, this time in five panels. The inspiration here is Guglielma Buema (also Guglielma da Milano), a medieval heretic. Here, it is the Aeolian mode that colors the piece. Guglielma preached the inclusion of women in the church as equals. The movements are to be interpreted as so many panels describing aspects of Guglielma’s life. The solemn “Guglielma e lo Sprito” (Guglielma and the Spirit) leads to subtle metrical play of “II volto rosso di Chiaravalle” (in the early church, the Holy Spirit was seen as an angel with a red face) before the chaconne of “Il guglielmiti di fronte all’inquisitore” introduces its own drama (the recording splendidly captures the rumbling bass pedal; Cooman’s virtuosity is splendid). The harmonic sweetness of “Guglielma e Andrea” leads to the “meditazione” of the final “La santa cena di Maifreda,” the holy supper celebrated by Maifreda as an act of revolution. This finale includes [a] fascinating fugue; and, actually, the almost tentative mezzo staccato pedal notes prior to the fugue itself are a stroke of inspiration, gloriously conveyed by Cooman.

Inspired by a stunning painting of the same name by the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, Viva la vida (Live Life, 2017) changes the mood of the disc totally. A wonky, skew-whiff waltz takes us to fairground mirrors and smokescreens. The invitation to enjoy life is clearly there, sonically, and Cooman seems to have a ball.

Finally, it’s back to religion and its transformative powers in Ecstasy (La transverberazione di Teresa d’Avila) of 2015. The ecstatic visions of Saint Teresa bring about a response from Ferrari that conveys that sense of ecstasy through an emphasis on particular, bright simultaneities: hence the framing use of “organo pleno” (literally, “full organ,” in the sense of full principal chorus). Regal is really the mot juste here.

The organ used is a completely mechanical neo-Baroque instrument (actually the largest entirely mechanical action instrument in Europe). It is a majestic, beautiful organ and one could hardly ask for a better recording. Cooman’s readings of the scores are impeccable in every way.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978