Fanfare

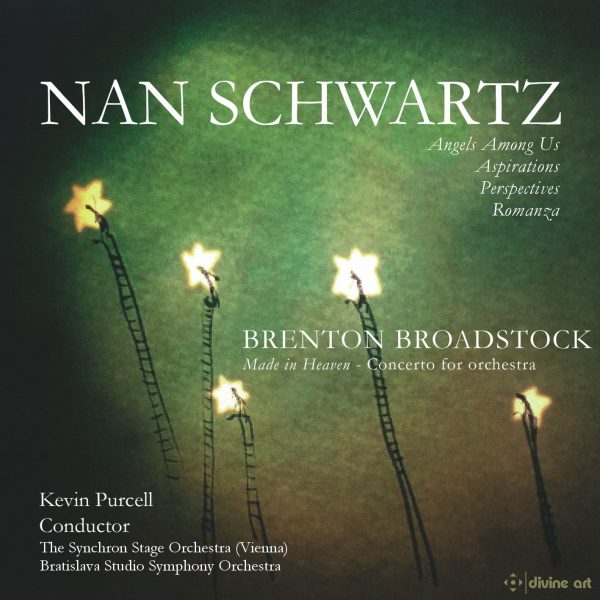

In 40:2, I wrote about the Concertino for Euphonium and Piano by Australian composer Brenton Broadstock, calling it “a major addition to the concerto repertory of the euphonium.” Needless to say, I was quite enthusiastic to receive this CD for review, for in the meantime, I’ve read somewhere (not in Fanfare) that this composer’s Made in Heaven—Concerto for Orchestra was being called a 21st-century masterpiece. You’ll get to my review and opinion of the work shortly, but I will also mention here that Nan Schwartz is a new composer to the Canfield ears, as well to the pages of our esteemed magazine. Since she is presented first on the disc, I’ll start with a few words about her and her works.

Schwartz grew up in a musical household (her clarinetist father created the famous Miller” sound, while her mother was a singer who performed with many luminous musicians including Tommy Dorsey), so perhaps her career in music was foreordained. It wasn’t, however, her original intention, which was to be a TV producer. Instead, a skiing accident laid her low for nine months, the enforced rest giving her the opportunity to pursue her secret dream of being a Hollywood composer. Her compositional break came when Los Angeles icon Jack Elliot encountered her music and commissioned her to write a piece for the New American Orchestra of which he was the co-founder and director. This commission resulted in her Aspirations, which opens this concert. She has gone on to receive a Grammy Award and seven Emmy nominations for her music for television.

Given her lineage from parents steeped in the big band tradition, and the fact that Elliot’s orchestra was also well connected with the jazz and film worlds, one might expect that Schwartz’s music would display influences from her heritage, and that it does. However, it also the case that some of her favorite composers include Ravel, Walton, and Shostakovich, and these have made their mark on her style as well. What one hears, then, is a music showing lots of disparate influences, but skillfully put together into a personal style that is Schwartz’s own. Not only does she have a very good ear for orchestral color, but she also has mastered the critical component of flow in a piece of music, such that her music never stagnates or wears out its welcome. Thus, in Aspirations, the piece begins in a rather classical idiom, with a gorgeous sweep of ideas, but around the six-minute mark takes a turn towards the jazz world, where a sultry and silky tenor saxophone solo takes over for a good portion of the remainder of the work. It’s neither completely jazz nor classical, but a very pleasing synthesis of the two worlds, and is absolutely gorgeous to my ears.

I confess that despite my writing, writing about, and listening to classical music almost exclusively, I have a soft spot in my heart for jazz and even good easy listening music. The latter was what I listened to on the radio when I was in my early teens and babysitting my younger siblings after they’d gone to bed, and this kind of music kept me—somehow—from falling asleep myself. So it would seem our esteemed editor (doubtless serendipitously) sent this CD to exactly the right reviewer. Thus, if Schwartz’s music sometimes verges into easy listening territory, it’s so good that I cannot help but like it. This style carries over into her other works including the following work, Perspectives, which features solo guitar and piano that weave in and around each other in clever interplay. The piece has a pronounced big band beat in certain portions of it, and sensual suavity in others. Perhaps my favorite of Schwartz’s works heard here is her Romanza for violin and orchestra—the violin is my favorite instrument, after all. It opens with just about the most gorgeous sequence of chords I’ve ever heard, and the beauty continues with the elegant lines in the violin all the way to the close of this five- minute work. I am left wanting more, in part because of the beautiful tone of violinist Dimitrie Leivici. Angels Among Us is the longest of the four works and features a trumpet solo throughout, and is more classically oriented than most of the other works. The trumpet a good hit of the time assumes a lyrical rather than heroic or military style, but occasionally wanders up into the jazz stratosphere, including the final lick that almost exceeds the kilohertz frequency that my ears can hear.

Melbourne-based Brenton Broadstock (b. 1952) studied with my friend, composer Don Freund (only five years his senior), although at a time before the latter joined the composition faculty of Indiana University. Broadstock also worked with iconic composer Peter Sculthorpe and is the composer of six symphonies and concertos for euphonium, tuba, piano, and saxophone, as well as several string quartets and even a chamber opera. He has received wide recognition in Australia, including the prestigious Don Banks Award from the Australian Council for his contribution to Australian music. Now, he seems to be in the process of bridging that big body of water between “Down Under” and “Up Above,” i.e., here in the North American continent.

His Made in Heaven is a four-movement concerto for orchestra, written in a pleasing tonal style that immediately thrusts its tunes and catchy rhythms into the listener’s brain. Like the music of Schwartz, this work is highly influenced by the jazz idiom, although to call it even “Third Stream” might be going too far. Prominent in the first movement is a two-note motive played mainly by the solo trumpet. The second movement is entitled “Flamenco Sketches,” but seemed much too laid back for that title until it finally got cranked up several minutes into it, while the third, “Blue in Green,” suggests to my ears a summer scene lounging around on the beaches along the Australian coast (which are quite a sight to behold, as my wife and I discovered on our visit there in 2009). The final movement, “All Blues,” is a lively affair, but not really blues to my ears. The opening, in fact, sounds as though it has wandered over from Ginastera’s Estancia, and a certain Latin flavor continues throughout the work, although I also hear echoes of Antill’s Corroboree Ballet. The piece does not attain the masterpiece status accorded it in the other magazine, but is very enjoyable to listen to, and many listeners would find it as delightful as I did, although I find the subtitle, Concerto for Orchestra, a hit misplaced. If you’re hoping for something along the lines of those written by Bartók, Lutoslawski, or Kodály, you may be disappointed.

To sum up. if your listening is confined to “long hair” music in whatever style, these works probably won’t be your cup of tea, but if you’re built of broader musical stock, I believe you’ll find much to savor in these five works. All of them could hardly be better and more idiomatically per¬formed than they are by Kevin Purcell and the Synchron Stage Orchestra in Vienna, who recorded Schwartz’s music. Purcell didn’t have far to travel to record the Broadstock work in Bratislava, Slovakia, which is only about an hour’s drive from Vienna, and the orchestra there does an equally fine job in presenting Broadstock’s music in the best possible light. Recommended then to—well, you know who you are.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

![Listen to the full suite of Marcel Dupré’s Variations Sur un Noël, Op. 20 from Alexander Ffinch’s #Expectations release today! listn.fm/expectations [in bio]](https://scontent-dfw5-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.71878-15/588904367_2327488161082898_8709236950834211856_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=105&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0xJUFMuYmVzdF9pbWFnZV91cmxnZW4uQzIifQ%3D%3D&_nc_ohc=m_5XHDUrNzIQ7kNvwH7VroP&_nc_oc=AdnE5ez1amPHafSqX8RAbrtoklQEZDNg2YSJeKTUeNjWMkdrhX1spETfVxF8w5BxRorFwnK0koTLsQgtv6ZVb8WB&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=LqDcj7tps28SdliQw9dYlA&oh=00_AfpHhm5bRHNRK4xpNnZ6vFPbOJa18KFBG9bPbevYMHEDBw&oe=696146AA)