Fanfare

It’s difficult to make really convincing electronic or electroacoustic music these days, not so much for any lack of fascinating timbres but in spite of so many! Maintaining interest often means a kind of stunted emotionality. Imagine French Baroque harpsichord music, with all its ornamental intrigue, but all in major keys. The inundation factor means that composers working in electronic media must up the game, which Grainne Mulvey and Christopher Fox accomplish with fluency, in¬trigue, and, above all, a winning intensity.

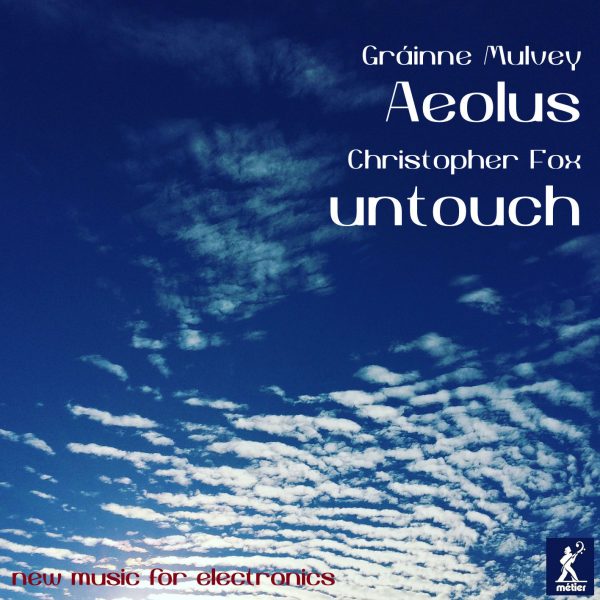

Mulvey’s Aeolus was written for a sculptor’s installation, using the sounds of an Aeolian harp, but any melodic or harmonic content Chopin or Schumann might have imagined is left behind for a universe of clusteral drones that are somehow simultaneously dense and transparent. The only imme¬diately recognizable sounds involve a backdrop of birds and open air. shimmering and gliding in and out of pleasant focus against motivically developed passages of varied articulation and fluctuating overtones. Ironically, there is something almost classical about the way elements unfold, even as points along the stereo spectrum are filtered in rapid succession or simply traversed. The birds invade, Hitchcock style, for a particularly effective climax where the wind is whipped into a maelstrom.

Comparatively speaking Fox’s Untouch is positively Spartan. If Mulvey’s clusters bespeak a kind of grainy purity, Fox goes all the way in this piece for percussionist who never actually touches an instrument, instead sweeping over it to produce sine tones. Temperament becomes Fox’s plaything as the piece steps slowly but boldly forward, note by note, harmonies only implied as tones intersect like the proverbial ships passing in the night. Repetition, at first the music’s major linear component, is slowly thwarted as the single line expands, each tone having its place along the stereo spectrum. Depending on how the music is heard, it can be hypnotic or amazingly complex. Like something by Steve Reich, the music presents a slow evolution, but there’s something beautifully innocent about the composer’s allegiance to simplicity or directness, as with many of Alvin Lucier’s beat pieces or like the equally hypnotic but much briefer second movement of Webern’s Variations for Piano.

Both Mulvey and Fox throw all matters of structure and form open to question and debate, and this is what makes the music so successful. Neither is concerned with effect or intrigue for their own sakes, and that certainty drew me into each world with interest and alacrity.

@divineartrecordingsgroup

Search

Newsletter

A First Inversion Company

Registered Office:

176-178 Pontefract Road, Cudworth, Barnsley S72 8BE

+44 1226 596703

Fort Worth, TX 76110

+1.682.233.4978

We noticed you're visiting from Latvia. We've updated our prices to Euro for your shopping convenience. Use Pound sterling instead. Dismiss